Rocket Men by Robert Kurson is the story of how three Americans changed the course of the Cold War forever. In 1968, the United States was falling behind the Soviet Union in the space race. They needed to put a man on the Moon—and they needed to do it fast. Kurson tells the story of how that impossible project, Apollo 8, came together. He shows how three astronauts—Frank Borman, Jim Lovell, and Bill Anders—became the first humans to orbit the Moon and make it back home.

Summary

The Space Race

1968 was a wild time in American history.

World War II was long over, but the country was weighed down by the devastating burden of the Vietnam War. Thousands of American soldiers were deployed, and the war divided the nation.

Meanwhile, the Cold War was at its peak. The Berlin Wall was constant news; the entire world was watching to see who would claim the bigger share of global power. America and the Soviet Union were locked in a long-lasting struggle, and they chose a new battleground to prove their dominance: the race to send a man to the Moon.

At first, the Soviet Union was winning. In 1957, Sputnik was launched, the world’s first satellite. America’s response came with the Vanguard rocket carrying a grapefruit-sized satellite—an event they broadcast proudly to the world. But only minutes after lift-off, it came crashing back onto the launch pad. That was a major embarrassment, and there were millions to witness it. The Soviets had the upper hand, and America knew what it needed to do to catch up: send a man to the Moon before the Soviet Union does.

In the meantime, NASA was already working on the Apollo program; its ultimate goal was to put a human on the lunar surface. The plan was laid out in five missions, each one building toward that giant leap:

- Apollo 7 would test the command and service modules in low Earth orbit.

- Apollo 8 would test the command, service, and lunar modules, also in low Earth orbit.

- Apollo 9 would push those same systems into high Earth orbit.

- Apollo 10 would take the full spacecraft into lunar orbit.

- And Apollo 11 would attempt the first landing on the Moon.

America’s Secret Plan

But with the Soviet Union’s rapid success towards putting a man on the moon, America couldn’t afford to wait until Apollo 11. By then, it might be too late. Behind the scenes, NASA made a dramatic call: instead of waiting for the lunar module to be ready, they would send Apollo 8 straight to the Moon. No practice run. No safety net.

If it worked, Apollo 8 would become the most important mission the country had ever attempted. But there was a huge catch. They had just four months to prepare—a process that usually took a year or more.

For the Most Important Project, You Need the Most Important Astronauts

Even if all the technical details could be sorted out in four months, the mission wouldn’t run on its own. They needed a crew.

Frank Borman

Frank Borman joined NASA after a successful career as a fighter jet pilot. Like most astronauts, he was politically conservative. For Borman, the mission was crystal clear: beat the Soviets. He had already told NASA this would be his final flight. Collecting rocks or pushing scientific boundaries didn’t matter—the real win was proving that America could get there first.

Jim Lovell

Born in 1928, Jim Lovell grew up in the teeth of the Great Depression. From an early age, he was fascinated by rockets, even writing to the American Rocket Society to ask for advice about careers in space. Unlike Borman, Lovell had a personal goal: to land on the Moon, and he worked steadily toward it. He wasn’t loud, he wasn’t flashy, but he could always be counted on when the stakes were highest. That skillset would later help him save two of America’s most critical space missions—Apollo 8, and then Apollo 13.

Bill Anders

Bill Anders was exposed to the world of rockets from a very young age. His father, Arthur Anders, was a United States Navy lieutenant, and that influence naturally guided Bill toward the Naval Academy. By the age of 23, he had earned his wings and was flying the twin-afterburner F-89 Scorpion. Like Borman, Anders was driven by the pressures and politics of the Cold War. He saw the space race as the best way to put his skills to use, and in 1963, he joined NASA to do exactly that.

The Stakes Were High for the Project

At the end of the day, we are talking about the most complicated man-made object ever built. The single points of failure on the rocket were unbelievably high, and even with the best crew possible, everyone knew that their return was far from guaranteed. And yet, there was a quiet, almost resigned acceptance of the risks—even among the astronauts’ wives.

“Chris, I’d really appreciate it if you’d level with me,” Susan said. “I really, really want to know what you think their chances are.”

“You really mean that, don’t you?” Kraft asked.

“Yes. And you know I do. I really want to know.”“How’s fifty-fifty?” he said.

“Good,” she told Kraft, “that suits me fine.”

The Smooth Operators on Space

It’s impossible to even grasp the sheer number of calculations and the level of accuracy a project like this demanded. NASA decided that Apollo 8 would orbit the Moon at exactly 69 miles above its surface. This number was chosen for a reason. The distance needed to be low enough that future astronauts heading to the lunar surface and back wouldn’t require a massive amount of propellant—but high enough to make sure that the orbiting spacecraft wouldn’t crash into the Moon.

“The question then became at what altitude to orbit. Kraft and his men wanted Apollo 8 to fly just 69 miles above the lunar surface, the same altitude at which the command and service modules would operate during a future landing mission. That required almost unimaginable precision, equivalent in scale to throwing a dart at a peach from a distance of 28 feet—and grazing the very top of the fuzz without touching the fruit’s skin. If that weren’t daunting enough, the Moon would be barreling through space at nearly 2,300 miles per hour. Toss a peach in the air at 28 feet and now hit the top of the fuzz with a dart. That’s what these trajectory experts were proposing to do. And soon everyone agreed to do it.”

“As before, a display flashed 99, the crew pushed a button to proceed, and the engine lit. Eleven seconds later, it stopped. By the calculations of the onboard computer, Apollo 8 was now in a circular orbit about 69 miles above the Moon.”

It’s hard to even imagine achieving that kind of precision from 238,855 miles away from home. And yet—they did it. I guess that’s why they call it rocket science.

Earthrise

Even though these are great scientific marvels, the magnitude of a project like this can’t really be shown with just numbers. It wouldn’t make much of an impact.

They needed something else. And that’s where Bill Anders’s camera came in. For the first time, someone pointed a lens back at us and caught the blue planet rising above the lunar horizon. As they came from the far side of the Moon, Anders took one of the most influential photographs of our time: Earthrise.

For the first time, humanity got to see itself.

Please Be Informed—There Is a Santa Claus

On Christmas Day, 1968, Susan Borman, Valerie Anders, and Marilyn Lovell were anxiously waiting for their husbands to come home. Back on the spacecraft, the astronauts were busy working on one of the most complicated maneuvers of the mission.

At the right moment, they were scheduled to fire the spacecraft’s engine—the SPS burn—to leave lunar orbit and set a trajectory back to Earth. The stakes could not have been higher. A miscalculation could mean either being lost in space forever or crashing into the lunar surface.

“Inside the spacecraft, the number 99 flashed on a display, asking the crew for the go-ahead to ignite the engine. If no one pressed the Proceed key, nothing would happen. Lovell looked to Borman. Borman nodded. Lovell reached forward, pressed Proceed—and then there was only silence.”

Four minutes later, mission control received a message from Lovell:

“Please be informed—there is a Santa Claus.”

Ideas that resonate with me

It’s actually… rocket science

The phrase “it’s not rocket science” gets flipped on its head here. It’s hard to even imagine the technical demands of a project this massive. Reading this book, I kept returning to one detail: the crew had no backup lunar module. If their single engine failed, they could be stranded in orbit forever—or flung into the void. It was a stark reminder that, for all the poetry of Earthrise, Apollo 8 was first and foremost a test of engineering nerve.

What a risk, and what a return…

Jim Lovell

I think Jim Lovell is one of the most important figures in American history.

The reason is simple: for some weird fortune, he had the chance to make mistakes and learn from them at the highest level. With that experience, he saved America twice. On Apollo 8, halfway home, he made one of those mistakes.

“Lovell had become a maestro at this job, ‘shooting’ stars, entering data, and aiming the sextant like a concert pianist playing a Steinway. In fact, Lovell had earned the nickname Golden Fingers for his proficiency at punching these keys. But he was human and not immune to a bad note. Early on December 25, Houston time, Lovell missed a step. He meant to enter Program 23 and then select Star 01. Instead, he entered Program 01 into his computer.”

The spacecraft, in very simple terms, became misaligned. Everyone was frustrated and tense—this was a life-or-death situation. And then Lovell improvised. He spotted the Moon, aligned it with the Earth, and managed to realign the spacecraft.

And…it worked.

They were back on track. This was not the first time Lovell had to troubleshoot under pressure; the book describes numerous situations from his Navy days where he delivered under extreme stress. And it would not be the last.

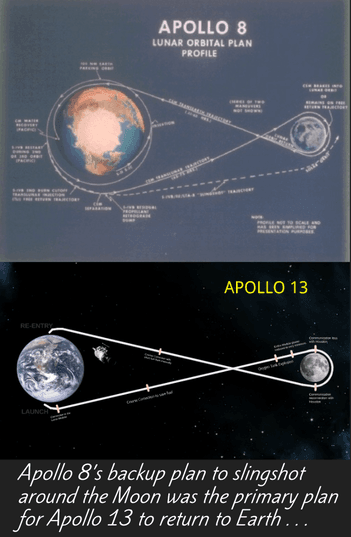

You might not know his name, but you’ve certainly heard the phrase “Houston, we have a problem.” That was Lovell, during Apollo 13. Years after Apollo 8, he became the mission commander for Apollo 13, which was meant to land on the Moon. But one of the oxygen tanks exploded, crippling the spacecraft. With the mission impossible and the crew in mortal danger, Lovell drew on all of his experience. He improvised in real-time, using the Lunar Module as a lifeboat—something it was never designed for. Like in Apollo 8, he manually navigated the spacecraft using the Earth’s horizon and the Sun as reference points during engine burns. And he brought the crew home.

Lovell saved the United States twice.

It’s official. I’d read anything Robert Kurson writes.

He only has four books, yet somehow, I’ve never read anything in this genre as compelling as his work. First, I read Shadow Divers, and it instantly became one of my favorite books of the year. Then, in the same month, I read Rocket Men and Pirate Hunters. If you’re looking for a book that’s both fun to read and packed with fascinating, real-world stories, look no further. Robert Kurson is a master at this type of non-fiction.

Parts that left a mark on me

“Apollo 8 has 5,600,000 parts and 1,500,000 systems, subsystems, and assemblies,” Lederer noted. “Even if all functioned with 99.9 percent reliability, we could expect 5,600 defects.” For that reason, Lederer concluded, Apollo 8’s mission would involve “risks of great magnitude and probably risks that have not been foreseen.”

Suddenly, an orb drifted dead center into the middle of the picture, and the shape of clouds and continents sharpened into view. For the first time in history, mankind was looking back at itself—at all of itself. Every human culture and language and idea and conflict and difference fit into a single picture.

“I think Apollo 8 was about leaving and Apollo 11 was about arriving, leaving Earth and arriving at the Moon. As you look back one hundred years from now, which is more important? I’m not sure, but I think probably you would say Apollo 8 was of more significance than Apollo 11.”

Coffee Chat

Summarize Rocket Men by Robert Kurson in one paragraph.

Rocket Men by Robert Kurson is the story of how three Americans nearly ended the Cold War. In 1968, the United States was falling behind the Soviet Union in the space race. They needed to put a man on the Moon—and they needed to do it fast. Kurson tells the story of how that impossible project, Apollo 8, came together. He shows how three astronauts—Frank Borman, Jim Lovell, and Bill Anders—became the first humans to orbit the Moon and make it back home.

How does Rocket Men by Robert Kurson compare to other Apollo 8 books like Apollo 8 by Jeffrey Kluger?

There’s another book about the Apollo 8 mission by Jeffrey Kluger called The Thrilling Story of the First Mission to the Moon. I haven’t read it yet, but it seems to cover much of the same context as Rocket Men.

One thing to keep in mind: Kluger co-authored Lost Moon, which became the basis for the famous movie Apollo 13. So he might bring some unique or novel perspectives to the story that Rocket Men doesn’t.

What new perspectives does Rocket Men offer on the Apollo 8 mission?

True—other books tell the same story, and I’m sure they’re just as accurate and well-written. But Robert Kurson delivers it in a way that really works for me.

His interviews play a key role. The chapters where he traces the astronauts’ lives—from their childhoods to how they became astronauts—add a layer of depth and humanity that makes the story feel personal. This is classic Kurson style, and it’s one of the things that makes Rocket Men such a compelling read.

How does Robert Kurson portray the Apollo 8 astronauts and their families in Rocket Men?

Kurson takes his time to show how the astronauts’ families were affected by the mission—something that doesn’t usually get much attention. To the world, they were astronauts. To their kids, they were just dads on a work trip. And they just wanted their dads to be home for Christmas.

He also shows the struggles and hardships their wives faced. It adds another layer of depth to the story. The epilogue continues this approach, covering their lives after the Apollo 8 mission.

In other words, Kurson gives us the whole picture—the complete story of an American hero.

How does Rocket Men balance technical mission details with 1968’s social and political unrest?

1968 was a wild time, not just for the United States, but for the entire world. I’m convinced that Kurson is one of the best authors to deliver this kind of narrative—he masterfully balances the political context with the core story. Most importantly, he does it all with the right flow.

Why did the Apollo 8 mission in Rocket Men feel more suspenseful than the actual moon landing?

First of all, Kurson knows how to write books like Hollywood movies. We’ve already established that. Second of all, the stakes were so high. With Apollo 8, there was no backup lunar module, no safety net, and just four months to prep for a journey that normally would take a year or more. Kurson makes you feel every heartbeat, every tense moment in the spacecraft. And also, in a sense, he makes the story human-centric, even though everything about this story is highly technical.

What do the family stories in Rocket Men reveal about the astronauts’ motivations?

Kurson doesn’t just tell you about the astronauts; he shows you their lives back on Earth. You see their wives—Susan Borman, Valerie Anders, Marilyn Lovell—waiting anxiously, checking in with mission control, worrying about a fifty-fifty chance of survival. Those moments humanize the astronauts. It’s clear their drive wasn’t just political or scientific—it was personal. They were carrying the hopes of their families, and that, Kurson shows, was a huge part of why they pushed themselves so relentlessly.

What historical background does Kurson include about 1968 in Rocket Men, and why does it matter?

1968 wasn’t just another year—it was chaos. The Vietnam War was raging, the country was divided, and the Cold War was in full swing. Kurson weaves all of that into the story, and it matters because it gives weight to the Apollo 8 mission. This wasn’t just another mission for the United States; it was a statement.

How does Rocket Men portray Frank Borman, Jim Lovell, and Bill Anders differently from other Apollo books?

I liked that Kurson gives each astronaut their own chapter, and it’s like sitting down with them personally. Borman comes across as laser-focused on beating the Soviets, Lovell as the calm, methodical problem-solver who literally saves the missions, and Anders as the disciplined, steady pilot whose skill and composure quietly anchor the team. By the time you finish, you don’t just know what they did—you feel who they were.

How did the book change the way I think?

“I think Apollo 8 was about leaving and Apollo 11 was about arriving, leaving Earth and arriving at the Moon. As you look back one hundred years from now, which is more important? I’m not sure, but I think probably you would say Apollo 8 was of more significance than Apollo 11.”