So, you’ve just received another dreaded “We regret to inform you” email.

After all your hard work, rejection stings.

I’m nearing the end of my PhD, and I still sometimes think about some of those emails I got when I was applying.

But you and I are not alone. Most PhD applicants get this email when they’re applying to graduate school.

It’s just a part of the process.

Even when you eventually get in, you will face rejection on a daily basis (journals, funding grants, positions, course release requests) they don’t get easier; you just get better at handling them.

But we can(and should!) reduce the chances of rejection.

The key is to ask the question why PhD applications get rejected, so you can avoid the same pitfalls and improve your chances next time.

Instead of feeling bad about it, it’s more productive to learn from it.

Table of Contents

You haven’t completely figured out your goals

The first thing the admission committee notices when they look through your application package is whether you’ve actually figured out your goals for the next few years.

If it seems like you haven’t, that’s a major red flag.

Admissions committees want to invest their time and attention in someone who’s already done that self talk, someone ready to begin their next chapter with intention and clarity.

There are a few ways they can tell.

If your personal statement doesn’t show genuine interest or direction, that’s one sign. If your professional goals don’t really need a PhD to achieve, that’s another.

Sometimes, applicants focus on the wrong things, like how excited they are about coursework, instead of showing they understand what research is for and why it matters.

If it’s unclear why you even want to pursue a PhD, that’s when doubts start to form.

Use these points to revisit your personal statement, your emails to potential supervisors, and your CV. If you haven’t written your statement yet, keep these in mind before you start. They’ll help you sound like someone who knows where they’re headed, and why this path makes sense for you.

Your personal statement doesn’t show the key elements that the admissions committee is looking for

But there’s something else, something really important, that students often overlook.

Even if you’ve done your research, figured out exactly what you want to do, and know why your goals need a PhD-level education, but your personal statement isn’t written well, all those well-thought-out ideas will go right over people’s heads.

You’ve worked hard to get here. You’ve kept your grades up, spent countless late nights on assignments, pushed through everything to reach this point. If you’ve decided to apply for grad school, chances are you’re already worthy of being selected for a program.

What stands between you and that opportunity is just a few documents.

The good news is that’s something you have control over. Unlike your GPA or your undergraduate research experience, things you can’t change now, you can write a clear, concise personal statement, a thoughtful email to a potential supervisor, and a strong CV.

Put the same effort into your writing that you did into getting here. Write clearly, show what you’re capable of, and close the gap between what you can do and what the admissions committee actually understands about you.

Make sure your statement of purpose shows that you’re genuinely interested in research, that you know what it involves, that you care about it, and that you have a specific direction you want to pursue.

You are applying for the wrong program

Sometimes, PhD applications get rejected simply because you’re applying to a program that requires a skill set you haven’t shown, or at least haven’t demonstrated clearly in your documents.

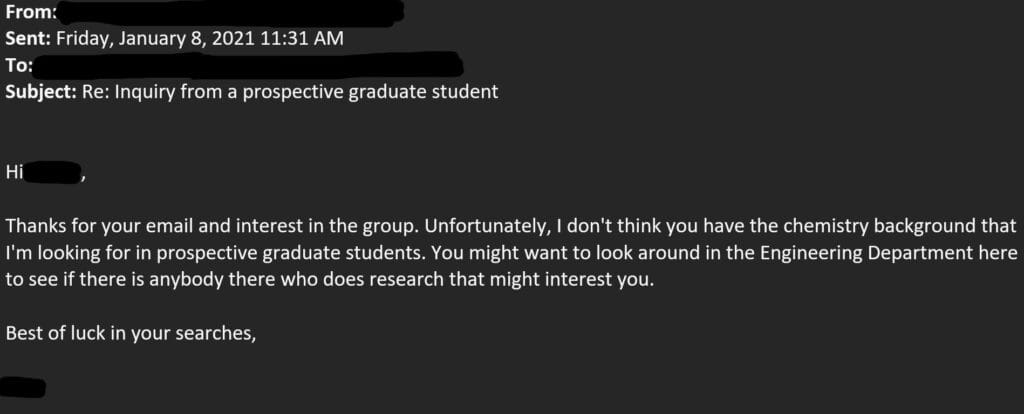

Here’s one of the emails I received when I was applying to graduate programs:

This kind of thing happens more often than you might think, especially when you’re writing emails to a potential PhD supervisor.

But a formal application is different. It involves money, time, and a lot more effort. That’s why it’s important to avoid these mistakes as much as possible.

The best way to avoid ending up in that situation is to ask yourself a few questions before applying:

- Does the research area you’re proposing actually fit within that discipline, or the kind of research you describe in your personal statement?

- Are you applying to the right discipline in the first place?

- Are you referring to the kind of work that’s happening in that department?

- Some disciplines are broad, while others are small and highly specialized. So are you really a good fit for what that department does?

In your documents, especially your personal statement, make sure you address something specific to the program you’re applying to. Show the admissions committee that there’s a clear reason you’re interested in their program.

Of course, parts of your statement will overlap across universities. That’s normal. But you should always make space for some thoughtful customization, enough to show that you understand what makes each program unique, and why you belong there.

No advisor fit

If you’re applying to a program, it’s important to understand the professors, the department, and what kind of research they do.

A lot of PhD applications get rejected because the students don’t have a clear sense of what that department actually focuses on.

Take chemistry, for example.

If you look at different chemistry departments across universities, you’ll notice that each one can be completely different, even though they share the same name.

One department might focus mostly on physical chemistry and spectroscopy, while another might lean toward organic chemistry. These are two totally different areas.

So if your background is in organic chemistry and you apply to a department that mostly works in physical chemistry, your chances of getting in are very low.

This matters even more in lab-based fields, where you’ll be working closely with a single advisor. But it’s also true in other disciplines, where you might not get an advisor right away but still need someone to guide your work. There’s no reason for a department to accept you if no one there can supervise your research.

Your interests don’t have to line up perfectly, but you should be able to show some connection with at least one faculty member in the department. Some PhD programs even ask that at least two professors be available to advise new students. So in those cases, you’ll need to find at least two people whose work fits with yours.

If you want to learn more about what faculty are working on, look into the research their students are doing. It gives a clearer idea of the lab’s direction.

Reaching out to professors before you apply can also help a lot. You might get a better sense of whether your research interests fit, and sometimes, they’ll even point you toward other faculty members working on similar topics.

Lack of research experience

Even if you don’t have much experience in the field you’re interested in, that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t apply to graduate school. Prior research experience isn’t a strict requirement in most cases.

But before applying, it’s worth thinking this through carefully because this is one of the most common reasons why PhD applications get rejected.

It’s not really about how much experience you already have. What matters is whether you show the potential and drive to carry out meaningful research in the area you are interested in. That said, it’s less risky for a supervisor to take on a student who already has a master’s degree and a few years of research behind them, someone with a proven foundation. But don’t let that discourage you.

Show that you understand your research area and that you’re genuinely excited about it. That’s what convinces people you’re ready to take that leap.

If you already have some experience, make sure to highlight it. Talk about what you worked on, what came out of it, and how that experience shaped your research interests. If you’ve worked in a lab, written a paper, or even just contributed to a project, mention it. Explain how it helped you realize that research is something you want to keep doing, and why it led you toward the specific path you’re on now.

Even if you don’t have much research experience, you can still write about why you want to do this, what excites you about it, and where your interests lie. What’s most important is showing that you know what you want to do with your degree, and that you’re determined to do it.

If you still have time before applying, try to get some experience first. For example, you could reach out to a professor and ask if you can help out on a project.

If you’re worried about applying straight to a PhD but are passionate about research, consider applying for a master’s program first. This is quite common in the U.S. and Canada. In fact, many admissions committees will recommend that path if you don’t yet have strong research experience.

Even if you start with a master’s, you can extend it into a PhD after a year or two once you’ve gained experience.

That’s exactly the path I took. Even though I was always interested in certain areas of chemistry, I completed my undergraduate degree in Materials Science and Engineering, a different field, and I didn’t have much chemistry experience at that point. Pursuing a master’s in chemistry was the most reasonable next step. After a year in the program, I was able to convert it into a PhD.

Weak letters of recommendation

For most graduate applications, you’ll need at least two letters of recommendation.

Choose your recommenders wisely.

Even when someone genuinely thinks highly of you, they don’t always give the strongest recommendation. A lot of the time, it’s because their attention shifts from your actual strengths(needed to finish a PhD successfully) to their own standards.

But that’s an unnecessarily high bar for a recommendation letter for graduate school.

Even if they truly want the best for you, they might just have a naturally cautious or pessimistic view when evaluating a student.

That’s not ideal in this situation.

If you and another student have similar qualifications, the recommendation letters can make all the difference.

For example, if your recommender writes something like, “Satisfactory, okay to work with, and needs some improvements in certain areas,” while the other student’s recommender says, “Excellent, one of the best students I’ve worked with,” both statements could technically apply to either of you. The only difference is the attitude of the recommender.

In a situation like this, you’re probably less likely to get in, not because you lack any requirements for the program, but just because of different attitudes of recommenders.

If all your recommendation letters say is that you did well in class and got straight A’s, that won’t really make your application stand out—because chances are, everyone else applying also got straight A’s, too.

The best recommendation letters highlight something specific about you, something that makes you stand out to the admissions committee.

That’s what matters.

Make sure that whoever writes your letter can speak about you in a strong, detailed way. Be very, very selective about who you ask. Ideally, it should be someone who knows you well, maybe a professor you’ve done research with or someone who taught a class where you did an exceptional project.

That way, they can write about something unique about you.

Try to avoid asking for recommendation letters from industry professionals. Of course, it depends on the person, but most of the time, they may not fully understand how important this letter is for your application. They might write a recommendation the way they usually do for anyone in the industry, and that might not work in your favor. It’s much better to choose someone from academia who understands how these things work.

Strong recommendation letters become especially valuable if you’re applying from a lesser-known or lower-ranked university. Rankings shouldn’t matter. But unfortunately, they sometimes do.

If you still have time before applying, try to build relationships with several professors. It’ll help a lot later on.

Low grades or test scores

This one is actually a more straightforward issue compared to some of the other reasons why PhD applications get rejected.

The main goal is to figure out how to apply even if your grades aren’t perfect.

First, don’t let lower grades stop you from applying.

GRE scores, for example, are becoming less and less important for PhD applications, since many universities have dropped them from their requirements. If your GRE scores aren’t great, focus on programs where the GRE is optional or not considered at all.

That said, your grades still matter. They can signal both your work ethic and your grasp of the subject. But grades aren’t the only way to show your ability. For instance, if your GPA isn’t great but you have several publications in your field, that can potentially outweigh your lower marks.

Professors usually look at your transcript for trajectory. A slow start in your undergraduate degree isn’t usually a deal-breaker if you show steady improvement over time.

For example, was there one particularly bad semester that dragged down your GPA? That just signals a temporary setback rather than a lack of ability or effort. You can even address it in your statement, explaining how you overcame the challenge and improved in later semesters. This can even turn a potential weakness into a strength.

Just be careful when discussing it. You want to show growth without selling yourself short in your personal statement.

Mistakes in the application

When you’re ready to apply for a graduate program, your grades are already set, and there’s nothing you can do about them. The same goes for any research experience you’ve already had.

At this stage, the one thing you can control is not making mistakes in your application.

You might be surprised how few students actually manage to submit a completely error-free application.

Here are a few examples to watch out for:

- In your personal statement, did you use the correct name of the university and the program?

- Did you mention faculty who are actually at that university and in that department?

- Did you provide everything the application asks for, without leaving anything out?

- Did you meet the deadline?

- When you request official transcripts from your undergraduate institution, they usually come in a sealed envelope addressed to a specific university. If you’re applying to multiple programs, it’s easy to accidentally send the wrong transcript to the wrong school, and that can lead to immediate rejection.

- Did you check for typos in your documents? If so, did you check again?!

Mistakes like these can signal a lack of attention to detail.

The safest approach is to double-check everything carefully and have someone else do the same before hitting “submit.”

Bad timing

Rejections aren’t always your fault.

The graduate application process isn’t a straight path. It’s unpredictable and depends on many factors that are completely out of your control.

Even if you do everything right, you can still get rejected.

One of the biggest reasons for this is faculty capacity. Sometimes it’s just a matter of the numbers:

- The faculty member you’d most like to work with might already have too many PhD students or no available funding.

- The department as a whole might have limits on how many students it can take at a time.

- You might actually be the stronger candidate, but another applicant’s research aligns more closely with funding that’s already approved.

It’s not a reflection of your abilities or potential.

This is also why you should apply to multiple programs.

Don’t put all your eggs in one basket.

Conclusion

The PhD application process is definitely one of those things that will keep you on your toes. Knowing what could go wrong ahead of time can save you a lot of time and effort.

Applications get rejected for many reasons. Some are completely out of your control, but others are things you can improve.

Being aware of all these possibilities gives you a much better chance of avoiding the avoidable mistakes, and putting your best foot forward.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why do most PhD applications get rejected?

Most of the rejections that are still in your control usually fall into one category: mistakes in your application package.

By the time you’re ready to apply, some things that might seem like deal-breakers—like your GPA or your undergraduate experience—are already set and can’t be changed. But that doesn’t mean your chances are over.

That’s exactly why admissions committees ask for documents like your personal statement, statement of purpose, or project proposals.

These documents are your chance to “fill the gaps” from your undergraduate years. Use them wisely. Focus on the things you can control.

Do grades really matter for PhD admissions?

Your grades do matter, but they aren’t the only thing you’re being evaluated on.

Think of your grades as a baseline. Almost all students applying to graduate programs have decent grades. You might not have straight A’s, but chances are your grades are good enough for the program you are applying to.

From that baseline, the admissions committee looks at many other factors to make its decision. Your previous research experience, publications, personal statement, and recommendation letters can all carry a lot of weight. Sometimes even more than your grades.

How important is research experience for a PhD?

Extremely important.

Admissions committees want to see that you understand what research really involves and that you can carry out independent work. Even small projects, internships, or a senior thesis can make your application stronger.

Make sure to include all your previous research experiences, no matter how small, in both your CV and your personal statement.

When it comes to choosing recommenders, pick people you’ve actually done research with, if possible. Their firsthand experience with your work carries much more weight than a general classroom recommendation.

Can I still get into a PhD program with low GRE scores?

Many graduate programs, especially in the U.S. and Canada, have waived the GRE requirement, either temporarily or permanently, or made it optional. This trend picked up during and after the COVID-19 pandemic.

If the GRE is optional, and if you have lower scores, it’s better not to include those scores with your application package.

Instead, focus your energy on what really matters: your statement of purpose, research fit, and recommendation letters.

How do I choose the right program to avoid rejection?

Start by analyzing your own interests.

If you haven’t figured out what kind of research you want to do, the admissions committee can usually tell right away, especially from your personal statement.

Next, look for programs that align with your research interests. Make sure there are at least two or three professors in the department working on the kind of research you want to pursue.

If you’re unsure whether these supervisors are looking for new graduate students, it’s best to reach out to them before you formally apply.

Finally, tailor your entire application package to each specific program you’re applying to.

What if my PhD application was rejected? Should I reapply?

Absolutely. Many successful PhD students get rejected the first time they applied.

Often, the rejection letter will mention why the program isn’t considering your application. Use that information to your advantage.

Take this as an opportunity to reanalyze your approach. If your personal statement needs improvement, now’s the time to work on it.

If you’re missing some research experience, try to gain some before your next round of applications.

Finally, focus on applying to programs that are a better fit for your interests.

Is it better to do a Master’s first if I keep getting rejected?

Yes, but it depends on a few things.

First, take a careful look at your application package. Make sure any rejections aren’t simply due to avoidable mistakes, things that you can control. Check that your personal statement is clear and coherent.

Next, try reaching out to professors whose research aligns with yours.

If you’ve done all of this and still got rejected, and if it’s not possible to further strengthen your application (for example, by gaining more research experience), then doing a master’s degree first would be a smart move.

Many universities even allow you to “extend” your master’s into a PhD. This way, you initially commit to a master’s but can continue on to a PhD without starting over.

A master’s degree helps you build research experience, and that experience makes you a much stronger candidate for a PhD. By the time you apply, you’ll have insider experience in academia and a much better chance of doing well in your PhD.