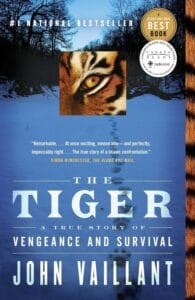

The Tiger by John Vaillant is a remarkable true story about a beekeeper who made the terrible mistake of meddling with the most dangerous animal in the wild, and paid the price with his life; and about the people who hunt it down, nearly getting killed themselves.

Table of Contents

Summary

A city at the edge of the world

In the far east of Russia lies a small village called Primorye. Although it is situated on the mainland, the people who live there often say it feels like an island. The village is cut off by massive rivers and endless stretches of forest, known locally as the taiga.

The nearest big city is Vladivostok, and interestingly, it’s closer to Beijing than it is to Moscow. To get to the capital, you’d have to take a week-long train ride across 5,800 miles. That’s how far removed this place is from the Russian capital.

It takes a lot to survive in Primorye

But isolation doesn’t mean freedom.

The people of Primorye still had to deal with a vicious government. The mid-1990s were a wild era. Russia was reeling from the collapse of the Soviet Union. The country was trying to rebuild its reputation, but the effort didn’t exactly stretch 5,800 miles to the east.

Primorye became Russia’s version of the Wild East, much like America once had its Wild West. Poverty was everywhere, and weak law enforcement haunted daily life. Survival meant more than just surviving the forest.

The king of Taiga: Amur Tiger

As if politics and poverty weren’t enough, the people of Primorye also shared their home with one of the most brutal predators alive: the Amur tiger. These animals are terrifyingly powerful. They eat everything from salmon to full-grown grizzly bears.

Yes, they eat bears…

But what makes Amur tigers even more frightening is their intelligence. They don’t just kill, they remember. They hold grudges.

Vladimir Schetinin, the former head of Inspection Tiger and an expert on Amur tiger attacks, has accumulated numerous stories like this over the past thirty years.“There are at least eight cases that my teams and I investigated,” he said in March of 2007, “and we all arrived at the same conclusion: if a hunter fired a shot at a tiger, that tiger would track him down, even if it took him two or three months.” (p. 138)

One man’s fatal mistake

In the taiga, the line between hunter and hunted is razor thin—especially when a tiger is involved. You make one mistake hunting a tiger, and suddenly you become the prey.

The tiger is a hunter, just the same as a man is a hunter. A hunter has to think about how to get his prey. It is different for boar and deer: if leaves or cones fall from a tree, that’s what they eat; there is no need to think. Tigers think.” (p. 165)

As one taiga hunter said, “The tiger will see you a hundred times before you see him once.” (p. 51)

Markov, a beekeeper in Primorye, made that fatal mistake. He hunted a tiger but failed to kill it. The tiger didn’t forget. Soon enough, Markov was the hunted. The book opens with his tragic death.

That’s when Yuri Trush, the leader of an Inspection Tiger unit, got the message: a man had been attacked near Sobolonye, a small logging community deep in the forest, sixty miles northeast of Luchegorsk. The story follows Trush as he tracks the same tiger, and nearly faces death himself in the process.

How People Hunted Tigers

Hunting a predator like this is obviously no easy task. But humans have been doing it for millennia. Two aspects of tiger hunting stood out to me.

First is endurance. Tigers can walk for days, but they can only sprint for short bursts. Humans, by comparison, can run for hours. That’s why hunters chose to track tigers in deep snow. In those conditions, tigers get tired quickly, so they become easier targets for humans.

Second is skill. The dominant strategy in tiger hunting wasn’t brute force; it was reading tracks. Trush and his crew were masters at it. A single paw print could tell if the tiger was injured, male or female, large or small, even whether it was in hunting mode or not.

A Dangerous Hunt

Armed with these tactics, Trush and his team finally managed to track and neutralize the tiger. What struck me most was that the animal wasn’t interested in anyone else; it was fixated on Trush, the leader.

That single-mindedness shows just how lethal, intelligent, and calculating these creatures are.

Ideas that resonate with me

Why this genre of nonfiction works

A good nonfiction book doesn’t just straight-up present facts; it tells a story.

The ones I love most are those where you can’t immediately tell if you’re reading a novel or a true story. Robert Kurson does this brilliantly. The Tiger by John Vaillant also fits into that category.

Well, almost…

Here’s my small complaint about the book. Although the information about Russia’s political atmosphere and life in the taiga was interesting, I felt a subtle disconnect between the main story and everything else. The back-and-forth between the main story and the surrounding context didn’t always come together coherently.

But I should not forget. The book is beautifully written. There were many moments where I just stopped and reread a sentence to appreciate the poetry of it. Here is one:

Trush was squeezing the trigger, which seemed a futile gesture in the face of such ferocious intent—that barbed sledge of a paw, raised now for the death blow (p. 274).

Why endurance shaped us more than we think

There was a piece of information in this book that made me think about human evolution in a way I hadn’t considered before.

A tiger can walk for days, but it can only run for short distances. For this reason, tiger catching was always done in the winter, preferably in deep snow, which shortened the chase dramatically (p. 95).

It clicked for me that this might be one of the reasons we humans managed to win the evolutionary game. So I started looking into research to see if this idea holds up.

One of the most influential studies on this topic is by Dennis Bramble and Daniel Lieberman, published in Nature in 2004. They argue that humans have unique anatomical and physiological traits that make us capable of sustained long-distance running. We can outperform most mammals in endurance, running for hours with relatively low energy loss. It turns out we’ve been refining this ability over millennia. Clearly, it was not an accident—it has been playing a huge role in our evolution all along.

Freedom is a ‘recognized’ necessity

I came across something on page 83 that caught my attention, though I didn’t fully understand it at first.

Karl Marx said that “Freedom is a recognized necessity.” I learned this in university, but I didn’t understand what it meant until I’d spent some time in the taiga. If you understand it, you will survive in the taiga. If you think that freedom is anarchy, you will not survive (p. 83).

In this context, necessity refers to the laws that govern life itself. A good examples are gravity or hunger. You can’t deny gravity. Or you can’t refuse to eat forever; if you do, you die. These are conditions you can’t escape, no matter how much you might want to.

But if you understand the basics of gravity, you can learn to use it to do interesting things, like dancing, running, balancing on two feet, and so on.

If you understand how nutrition works, you can design a healthy diet. You’ve recognized that hunger is unavoidable, yet you’ve learned to work with it, even to your advantage.

Freedom works in the same way.

Real freedom isn’t the absence of laws or limits. It’s the recognition of life’s necessities—and the ability to structure them in a way that empowers us. True freedom emerges when people come together to rationalize fair, well-intentioned laws that allow us to live our best lives within those boundaries.

Parts that left a mark on me

One reason people find it so difficult to describe how they feel is that they have never been asked. It is understood that life is hard and men, especially, are expected to suck it up and gut it out. If you need a counselor, confessor, or escape hatch—that’s what vodka is for (p. 199).

Humans have hunted tigers by various means for millennia, but not long ago, there was a strange and heated moment in our venerable relationship with these animals that has been echoed repeatedly in our relations with other species. It bears some resemblance to what wolves do when they get into a sheep pen: they slaughter simply because they can, and, in the case of humans, until a profit can no longer be turned (p. 94).

In that moment, Sokolov shifted into a different mode; it was as if the clouds of fear parted to make way for another emotion, much as they had for Jim West when he heard the bear attacking his dog. “I just got mad,” said Sokolov. “Instinctively, I punched the tiger in the forehead, between the eyes. He roared and jumped away. Then my partner came to help me.” (p. 207)

“The situation today is very different from the situation ten years ago because, if I encounter a tiger in the taiga these days, I am encountering an injured tiger more often than not.” (p. 289)

As long as the footpath, logging road, frozen river—or highway—is going more or less in the desired direction, other forest creatures will use it, too, regardless of who made it. In this way, paths have a funneling, riverlike effect on the tributary creatures around them, and they can make for some strange encounters (p. 13).

Coffee chat

Summarize The Tiger by John Vaillant, the true survival story of Vladimir Markov and the Amur tiger.

The Tiger is the story of a beekeeper, Vladimir Markov, in Primorye, Russia. He made a huge mistake by trying to hunt a tiger and missed. Unfortunately for him, the tiger didn’t forget. It started tracking him and eventually caught up with him. Then there’s Trush, the leader of a tiger inspection unit, who comes in to handle the situation. Unlike Markov, Trush doesn’t miss, but he still comes really close to meeting his end.

Explain why the Amur tiger tracked down Vladimir Markov in The Tiger.

Tigers hold grudges. The tiger remembered Markov. These Amur tigers aren’t just strong; they’re smart and calculating. This wasn’t random. It singled Markov out because of what he did. It’s really interesting to think about how methodical these animals can be.

What is the deeper meaning of human–tiger conflict and survival in The Tiger?

On the surface, it’s man versus predator. But on a deeper level, it’s about endurance, intelligence, and knowing your limits—both as humans and as animals. Reading it, I started thinking about why humans survived evolution’s challenges: we’re built for long-distance endurance, unlike tigers, for example.

There’s also a philosophical side to it: freedom isn’t about doing whatever you want. It’s about understanding life’s rules and working within them. In the taiga, that distinction isn’t just philosophical, it’s life or death.

Describe the main themes of survival, nature, and the Russian Far East in The Tiger.

The book is layered. Survival is the big theme. You’ve got humans, tigers, and the environment all constantly pushing against each other. Nature is brutal and smart; the Amur tiger is the perfect example. And the Russian Far East—Primorye—is more than just scenery. Its isolation, poverty, and harsh winters shape their lives. Life there is a test of skill and endurance.

How does John Vaillant combine storytelling and real events in The Tiger?

You’re following Markov’s story like a suspense novel, but you also get context about Russian life in the 1990s, tiger biology, and hunting techniques. It never feels like dry nonfiction, though sometimes the background info feels a bit disconnected from the main story.

What was the political and social context of Primorye, Russia, in the 1990s?

Primorye was Russia’s “Wild East.” After the Soviet Union fell, the government barely made it that far east. Law enforcement was weak, poverty was everywhere, and survival often meant navigating both human threats and natural ones. Isolation amplified every danger—social, political, environmental—and everything in between.

What does the title The Tiger symbolize?

Obviously, there’s the tiger itself. It’s the central theme of the story. But symbolically, it’s also nature’s intelligence, power, and unpredictability. The tiger shows the limits humans have to respect to survive. It’s a threat, yes, but also a reminder to respect the rules of life.

How does The Tiger compare to other nonfiction books about human–tiger conflict?

It sits between a thriller and nonfiction. Unlike purely academic books, it pulls you into the story. Very similar to Robert Kurson’s work. You can’t always tell if it’s a novel or real events. What makes Vaillant’s book stand out to me is how he frames survival not just in terms of humans and tigers, but also politics, environment, and evolution, and weaves it all into a single story.

How did the book change the way I think?

Reading The Tiger really got me thinking about human physical endurance and how it shaped our evolution. We often focus on intelligence or tools when we think about why humans survived, but this book reminded me that our physical endurance was a very important part of our evolution.