Snapshot

Why can’t we all just get along?

You’ve probably heard this question everywhere, on the news, on social media, even on the road. It sounds simple. But it points to something deeper about how we think.

Take abortion laws, for example. You might hold a stance that feels completely reasonable, and obvious to you. But to someone else, that same stance looks wrong, wrong on so many levels.

Now imagine debating it. You both bring facts, studies, and every piece of evidence you can find. And yet, at some point, the discussion hits a wall. We’ve seen it over and over again. You’ve both said everything that can be said, the science, the logic, the “common sense.” And still, you disagree. Your gut feeling holds onto your narrative, no matter what.

A gut feeling that murmurs in your ear, “No, I’m right about this.”

But if you’re right, that means the other person must be wrong. But the chances are that they feel the same way about you!

Can you just shrug it off and say, “Oh, that person doesn’t know what they’re talking about,” and close the argument?

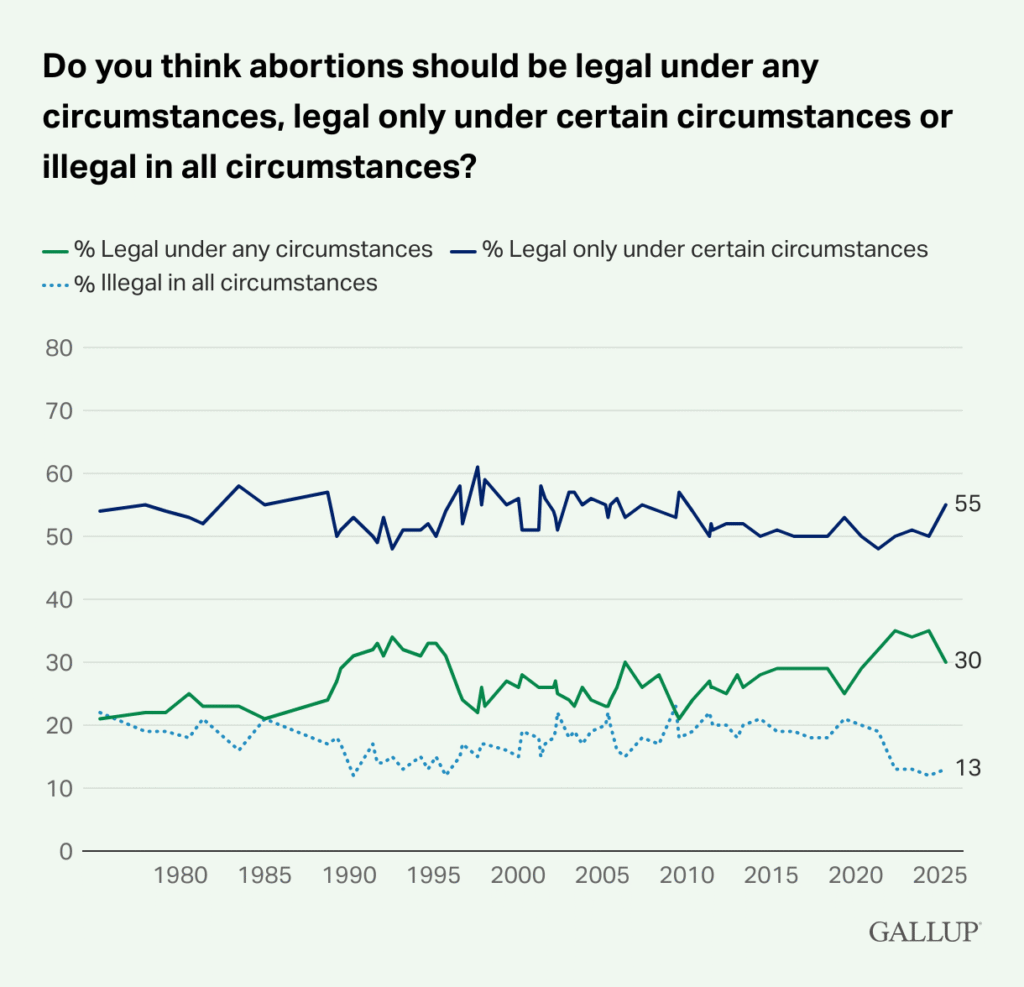

Well, here’s an interesting statistic.

In a May 2025 poll by Gallup, 51% of U.S. adults say they identify as “pro-choice,” and 43% say they identify as “pro-life.”

No matter which “camp” you’re in, you’ve got to admit: we can’t just rationalize the fact that half the people in a country don’t know what they’re talking about. something else, something much deeper, that keeps us holding onto our own narrative, no matter what the facts or evidence say.

Neither of you can prove that gut feeling right or wrong. So where does it come from? What shapes it? And if we know someone’s gut feeling on one moral issue, say, abortion, could we predict how they’ll feel about another, like gun control?

These are the questions answered in A conflicts of Visions by Thomas Sowell.

Table of Contents

Part 1: Patterns

1. The Role of Visions

It’s easy to assume that conflicts like these exist because we don’t have the “facts” right. But more often than not, especially in the modern world, getting the facts is just a touch of a button away. And once we have them, we can bring evidence to try to falsify one theory against another.

Evidence is fact that discriminates between one theory and another. Facts do not “speak for themselves.” They speak for or against competing theories. Facts divorced from theory or visions are mere isolated curiosities. (Page 16)

So if there are conflicts of interest, we might think we could just propose a theory and then test it against existing ones. But concepts aren’t like equations.

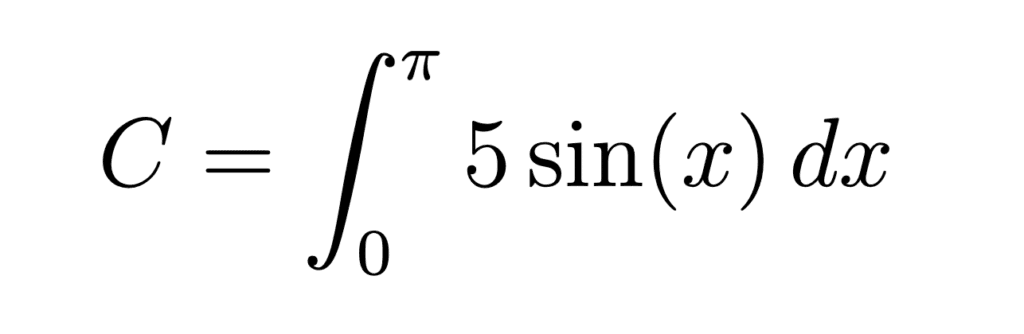

Let’s say we have two mathematical equations to solve, and both come from the same system, meaning C is a constant, no matter the equation. Let’s try it.

The first equation is: A + B = C. We already know A = 6 and B = 4. Falsifying it is simple—we all know the answer: C = 10.

Now, imagine we can write another equation for the same system, like this:

It takes a bit more knowledge than before, but if someone takes the time to go through already proven theories, we still get the same answer: C = 10.

Perfect!

No matter what angle we look at this system from, we can prove that C is always 10. If we could solve all our life problems like this, there would be no wars, no conflicts, no confusion.

But here’s the problem: most of the conflicts we face in daily life aren’t mathematical. They’re philosophical. And there is no right answer to a philosophical theory. In fact, that’s the whole point of philosophy in the first place.

The knowledge we use to prove a theory has, and always will have, holes in it.

Sowell argues that we fill those gaps, these “holes” in our knowledge, with visions. The problem is, you can’t just prove a vision. You simply have it, like a gut feeling.

And that’s why there are, and always will be, conflicts.

They don’t arise from the available theories or evidence, but from the gaps in knowledge we have to fill in order to create those theories and test them against the evidence.

Visions fill in the necessarily large gaps in individual knowledge. Thus, for example, an individual may act in one way in some area in which he has great knowledge, but in just the opposite way elsewhere, where he is relying on a vision he has never tested empirically. A doctor may be a conservative on medical issues and a liberal on social and political issues, or vice versa. (Page 17)

Conflicts of vision dominate the human experience, nearly all the struggles in politics, economics, and culture can be traced back to a clash of different visions.

The purpose of the book is to show how recurring historical and intellectual conflicts reflect a clash of visions about human nature, knowledge, and morality.

2. Constrained and Unconstrained Visions

So what are these different visions?

Sowell argues that there are many, but they all narrow down to just two: the constrained and the unconstrained visions.

What is the definition of constrained vision?

The constrained vision assumes that human nature is limited and self-interested.

Moral progress doesn’t come from trying to fix these flaws, but from learning how to manage them. That’s why this view places its faith in institutions, traditions, and systems, markets, laws, and norms, that channel our imperfect motives toward something socially useful.

What is the definition of unconstrained vision?

The unconstrained vision starts from the belief that human nature can be improved and reach its full potential.

With enough reason, education, and moral effort, social problems aren’t just manageable, they’re solvable.

This view places its trust in intentions, moral responsibility, and rational design, aiming not to accept the world as it is, but to shape it into what it ought to be.

3. Visions of Knowledge and Reason

When you’re watching a debate, have you ever caught yourself thinking, “What on earth is this person talking about? How can they not understand something so simple?”

Well, here’s the rational answer: their definitions—even for the most fundamental things—might be completely different from yours.

Take the word “knowledge,” for instance. It carries two very different meanings within these two visions.

In the constrained vision, knowledge is something we accumulate slowly, over time, through experience and evolved processes like the free market or cultural traditions. Since this vision begins with the idea that human nature is inherently flawed, it assumes that individuals can’t simply create knowledge on their own.

On the other hand, the unconstrained vision starts from the belief that human beings can reach the intellectual potential they aspire to. Here, knowledge is something we obtain through reason and intellect.

In other words, the constrained vision trusts processes, while the unconstrained vision trusts experts.

Both see the same word, “knowledge”, but through entirely different lenses.

| Aspect | Constrained Vision | Unconstrained Vision |

|---|---|---|

| View of Social Order | Trusts systemic processes like markets, traditions, and evolved institutions. | Trusts intentional processes—deliberate planning and expert design. |

| Examples | Markets, rule of law, cultural traditions. | Central planning, judicial activism, rational social design. |

| Source of Trust | Relies on processes that harness human limitations for social good. | Relies on experts and moral reasoning to shape society. |

4. Visions of Social Processes

Consequently, these two visions hold very different ideas about how societies evolve and function.

Adam Smith’s “invisible hand”

For instance, in the constrained vision, social order emerges from norms that have evolved over generations. It sees the feedback we get from backlash, and the trade-offs people make along the way, as our best teacher. Those lessons are what really move people forward.

A good example of this way of thinking comes from the economics giant Adam Smith. His book, The Wealth of Nations (An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations), published in 1776, captures this idea perfectly.

Adam Smith’s “invisible hand” means that when people act in their own self-interest, like a baker selling bread to make a living, they often end up helping others without even trying. The baker makes good bread to attract customers, people get food, and everyone benefits. Smith used this idea to show that society doesn’t always need strict control to work well. When people freely trade and pursue their own goals, the economy can organize itself naturally, as if guided by an invisible hand.

Rousseau’s “general will”

On the other hand, the unconstrained vision assumes that people are much more in control, that they can consciously make the right decisions, and that doing so moves society forward.

A good example of this comes from Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778), the French philosopher. His 1762 book, The Social Contract (Du contrat social), captures this vision. One of the best examples is Rousseau’s idea of the general will.

Rousseau’s “general will” means that the best decisions for society come from the collective will of its people, not just individual desires. When everyone focuses on what’s good for the community as a whole, rather than only what benefits themselves, society can act in a fair and just way. Rousseau believed that following the general will actually helps people live freely, because true freedom comes from obeying rules they see as serving the common good.

| Aspect | Constrained Vision | Unconstrained Vision |

|---|---|---|

| View of Conflict | Sees conflict as inevitable due to human limitations; resolution requires compromise and trade-offs. | Views conflict as avoidable through reform, education, and moral progress. |

| Examples | Tends toward systemic interpretations of issues like crime, war, and economics. | Favours moralistic interpretations, focusing on justice, intentions, and reform. |

5. Varieties and Dynamics of Visions

But these visions don’t exist in their pure form in the real world. Most thinkers from both sides fall somewhere along the spectrum.

Nobody sits at the extreme.

One reason is that visions evolve over time. People merge, mix, and adapt their visions depending on historical knowledge, cultural shifts, and other influences. In this book, these are called “hybrid visions.”

Some examples are:

1. Sweden’s Market Welfare Balance

Sweden is a good example of a hybrid vision. It runs on free markets and global competition, but also maintains strong safety nets like healthcare and worker support. It acknowledges that people are driven by self-interest (the constrained view), yet it still believes society can push for the collective good (the unconstrained view). Its success comes from balancing both, harnessing capitalist energy while promoting social fairness.

2. The New Deal’s Pragmatic Reformism

Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal is another example of a hybrid vision. It didn’t reject capitalism, it reshaped it. The New Deal recognized market limits and self-interest (the constrained view) but also aimed for moral progress through social security, public projects, and financial reform (the unconstrained view). It showed that systems can evolve without being torn down, proving that stability and fairness can go hand in hand.

3. Singapore’s Guided Capitalism

Singapore is another example of a hybrid vision. Strict laws, strong institutions, and economic incentives maintain order and drive productivity, while heavy investment in education, housing, and healthcare pushes social progress. It channels self-interest toward collective goals, showing how smart policy and leadership can create a stable, high-growth society.

4. Carbon Pricing as Moral Economics

Modern environmental policy is another example of a hybrid vision. Tools like carbon taxes or trading schemes work with self-interest (the constrained view) while pursuing a moral goal: protecting the planet for future generations. Effective policies balance fairness, efficiency, and accountability, showing how practical incentives and ethical goals can work together.

The dynamics of visions continue to dominate our lives.

This is why, no matter what political or economic stance people hold, struggles keep going, and often resurface after centuries. They are rooted in the same two core visions: constrained and unconstrained.

Part 2: Applications

Now that the “theory” of the two visions and their dynamics has been explained, Sowell turns to their applications; how constrained and unconstrained visions show up in the real world.

6. Visions of Equality

“Equality” has become a hot topic these days. You hear it in debates about the gender pay gap, college admissions, and all sorts of other issues.

The reason these debates never end is simple: the constrained and unconstrained visions see “equality” in completely different ways.

In the constrained vision, everyone gets equal opportunity, but inequality is just part of life.

It comes from differences in talent, effort, and circumstances.

On the other hand, the unconstrained vision thinks equality is something we have to actively make happen. It’s up to us to fix inequalities, rather than just letting resources be available to everyone. The unconstrained vision sees inequality as a flaw in the system; the constrained vision sees it as a natural byproduct of liberty and diversity.

From this angle, trying to force equality of outcomes can actually break the systems that keep society running. That’s why these two visions are always clashing when it comes to welfare, taxes, affirmative action, and education funding.

| Example | Constrained Vision | Unconstrained Vision |

|---|---|---|

| Gender pay gap | Differences in pay are largely expected because of variations in careers, experience, roles, and talent. Inequality is a by‑product of these differences. (mckinsey.com) | Pay gaps are seen as flaws in the system that must be corrected through active intervention and policy (e.g., legislation, pay‑equity measures). (payequity.gov.on.ca) |

| College admissions | Equal opportunity is given, but unequal outcomes are expected because of talent, background, effort, and circumstance. | Inequality in outcomes is viewed as evidence that the system needs reform; outcomes should be actively shaped via policy (e.g., affirmative action). (civilrightsproject.ucla.edu) |

| Income/wealth inequality | Unequal results are inevitable given differences in talent, choices, starting positions, and incentives; the focus is on process and opportunity. (pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) | Large inequalities are seen as systemic defects requiring meaningful redistribution or structural change to achieve more equitable outcomes. |

7. Visions of Power

The constrained vision sees “power” as something spread out through institutions and checks and balances. And here, institutions don’t just mean government. They mean the political and economic processes, like the free market, price floors, price ceilings, and so on. This vision assumes freedom depends on keeping power from concentrating too much.

On the other hand, the unconstrained vision sees power as more “hands-on.” It can be actively used by people or groups who are in a position to do so. That means the unconstrained vision is more comfortable with centralized authority to maintain social and economic balance. In contrast, the constrained vision assumes centralized authority is inherently corrupting, so it’s necessary to limit its power and channel it through institutions and processes that prevent abuse.

| Aspect / Example | Constrained Vision | Unconstrained Vision | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| View of Power | Power is dispersed through institutions and systemic processes (not just government)—like markets, price floors, price ceilings. Freedom depends on limiting concentrated power. | Power can be actively wielded by people or groups entitled to it. Centralized authority is acceptable if it maintains social or economic balance. | Sowell 2008: hoover.org |

| Institutional Focus | Trusts processes to check and balance power; centralized authority is assumed corrupting and must be constrained. | Trusts leaders or authorities to wield power directly to achieve desired social or economic outcomes. | FEE : fee.org |

| Historical Examples | Limited government intervention, decentralized wartime decision‑making, checks on monarchical or executive power. | Strong government interventions during crises (e.g., New Deal, wartime central planning), centralized leadership in war or reconstruction. | SWJ : smallwarsjournal.com |

| Practical Examples | Market regulation to prevent monopolies, independent judiciary, decentralized organizational decision‑making. | Executive‑led reforms, targeted policy interventions, and central planning to correct systemic problems. | DailyEconomy 2023: thedailyeconomy.org |

8. Visions of Justice

Justice, like equality, is defined differently in each vision.

The unconstrained vision believes in cosmic justice. Justice is achieved when moral desirability is met. It’s what you might call “result justice”: fairness is judged by how things turn out. If one group ends up with less wealth or opportunity than another, the unconstrained vision sees that as an injustice to be corrected, even if the same rules were applied.

On the other hand, the constrained vision focuses on process justice. Justice comes from impartial rules. Impartial rules are applied objectively, without bias or prejudice, ensuring everyone is treated equally based on merit and without outside interference.

In short, the constrained vision focuses on fairness in the process, while the unconstrained vision focuses on fairness in the outcome.

Put another way: the unconstrained vision prioritizes intentions and outcomes; the constrained vision prioritizes procedures and trade-offs.

| Example | Constrained Vision (Process Justice) | Unconstrained Vision (Result Justice) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Criminal Sentencing | Equal application of laws and sentencing guidelines, treating everyone the same regardless of background. | Adjusting sentences to account for social context or systemic bias to achieve fairer outcomes. | Our Commons |

| University Admissions | Merit-based admissions; everyone competes under the same rules, and outcomes may differ. | Affirmative action or quota systems to correct historical inequalities and achieve more equitable outcomes. | PBS |

| Wealth Redistribution / Taxation | Neutral tax rules applied equally to all; inequalities are expected due to talent and effort. | Progressive taxation and social programs aimed at reducing inequality and achieving fairer results. | Number Analytics |

9. Visions, Values, and Paradigms

Looking at all these dynamics between the constrained and unconstrained visions, it’s easy to see why most political, social, and economic battles never end. They aren’t just about facts. They’re about visions.

People tend to reason within their own vision, not across visions. So, like in the example from the introduction, even when all the facts are laid out, we still get the sense that the other side is “somehow” wrong.

Thomas calls this the “self-reinforcing paradigm,” which shapes our entire belief system.

The key takeaway from the book is: political and moral debates aren’t primarily about disagreement over facts. They’re rooted in conflicting assumptions about human nature, morality, and knowledge.

Ideas that resonate with me

Not a summer read

I started this book thinking I could finish it in a week. Well… that didn’t go so well.

It ended up taking me a month.

It’s not just that the book is built on a well-crafted original thesis—it’s dense. Every sentence counts, just like in any other Thomas Sowell book. For the first time, I got a highlighting warning on my Kindle because I was highlighting every other sentence.

After chipping away at it for about 30 mornings, that’s 30 hours, I finally finished it.

And it was completely worth the time.

The brave new world and conflict of visions

The same month I was reading this book, I was also reading Brave New World by Aldous Huxley.

If there had to be a fiction version of this non-fiction book, it would be Brave New World.

For example, here are some quotes from Brave New World:

“Just to give you a general idea,” he would explain to them. For, of course, some sort of general idea they must have if they were to do their work intelligently—though as little of one, if they were to be good and happy members of society, as possible.

For particulars, as everyone knows, make for virtue and happiness; generalities are intellectually necessary evils. Not philosophers but fretsawyers and stamp collectors compose the backbone of society. (page 4, Brave New World by Aldous Huxley)

“Old?” she repeated. “But the Director’s old; lots of people are old; they’re not like that.”

“That’s because we don’t allow them to be like that. We preserve them from diseases. We keep their internal secretions artificially balanced at a youthful equilibrium. We don’t permit their magnesium-calcium ratio to fall below what it was at thirty. We give them transfusions of young blood. We keep their metabolism permanently stimulated. So, of course, they don’t look like that. Partly,” he added, “because most of them die long before they reach this old creature’s age. Youth is almost unimpaired till sixty, and then, crack! the end.” (page 111, Brave New World by Aldous Huxley)

This book shows a world where an unconstrained vision clashes with the constrained vision at their extreme ends, showing what happens when these two extremes collide.

Why only two visions?

Why are these visions binary? Why is it possible to shrink all the hybrid visions down to just two? Why not four or three?

People are complicated, sure, and we all have plenty of moral and thinking quirks. But research shows that a handful of patterns explain most differences in political attitudes. Sowell’s two visions line up with one of the biggest patterns: do we see human nature as limited, or do we think people can be shaped toward some perfect ideal?

Socialism and capitalism vs constrained vision and unconstrained vision

This was the first question that popped into my head while reading the book:

Does the constrained mind line up with right-wing ideologies, and the unconstrained mind with left-wing ideologies?

At first glance, it might seem that way. Sowell says people with a constrained vision prefer to rely on “institutions.” That sounds a bit like socialism, where institutions play a big organizing role.

But Sowell actually associates the constrained vision with capitalism, not socialism. The difference is in what he means by “institutions.” For him, these aren’t tools of central control—they’re evolved systems, like markets, traditions, and the rule of law, that help manage human limitations. In other words, institutions here refer to systematic processes, not government entities.

So, who’s right?

This is the big question—what it all really comes down to.

Like I mentioned at the beginning, if a country is split right down the middle, how can we ever get along?

After all, who’s right? Is the rest of the country wrong? The truth is, we’ll never really know. That might sound like a flimsy answer, but there’s a silver lining.

Looking back over history—30,000 years into the past, and then to now—one thing is clear: things got better. Much better, especially in the last 2,000 years, where both visions coexisted. Both constrained and unconstrained visions have played a role in getting us here.

Because at the end of the day, humans have done one thing and one thing only for progress: defining boundaries.

And we can’t create a boundary without two phases, without two perspectives.

That’s why we need both of these visions to move forward.

If I were to challenge the premises of A Conflict of Visions, what potential weaknesses or counter-arguments might I raise?

This is one of those ‘good’ books, that once you understand the basic premise of it, you start seeing it everywhere.

That said, if I had to add something, one question that kept coming to mind while reading was: what gives us these separate visions in the first place? Is it biological or sociological? In other words, is it nature or nurture?

But that question wasn’t really within the scope of this book anyway.

Parts that left a mark on me

Conflicts of interests dominate the short run, but conflicts of visions dominate history. (Page 10)

Evidence is fact that discriminates between one theory and another. Facts do not “speak for themselves.” They speak for or against competing theories. Facts divorced from theory or visions are mere isolated curiosities. (Page 16)

Visions fill in the necessarily large gaps in individual knowledge. Thus, for example, an individual may act in one way in some area in which he has great knowledge, but in just the opposite way elsewhere, where he is relying on a vision he has never tested empirically. A doctor may be a conservative on medical issues and a liberal on social and political issues, or vice versa. (Page 17)

How did the book change the way I think?

Being open-minded to ideas that your gut feeling tells you not to can be one of the best ways to fill the gaps in our knowledge of how the world works.

Coffee chat

Summarise A Conflict of Visions in one paragraph

In Conflicts of Visions, Thomas Sowell argues that there are two distinct categories of visions that have dominated history—and continue to do so today.

So what are the underlying assumptions behind the very different ideological visions we see contested in modern times?

There are two main types, although most real-world ideologies are a mix of both in varying proportions.

The first is the constrained vision, where people believe that human nature is inherently flawed. Progress, then, comes from learning from our mistakes and trusting tested economic and political processes like the free market, the rule of law, and established institutions.

The second is the unconstrained vision, which believes we are capable of improving ourselves and reaching our full potential through reason, education, and moral effort. This vision puts its trust in intentions, individual intellect, and moral responsibility.

What are the main visions in A Conflict of Visions and how do they differ?

The two main visions discussed in Conflicts of Visions are the constrained and unconstrained visions.

The constrained vision assumes that human nature is limited and self-interested. Moral progress doesn’t come from trying to fix these flaws, but from learning how to manage them. This view places its faith in institutions, traditions, and systems—markets, laws, norms—that channel our imperfect motives toward something socially useful.

The unconstrained vision, on the other hand, starts from the belief that human nature can be improved and reach its full potential. With enough reason, education, and moral effort, social problems aren’t just manageable—they’re solvable. This view trusts in intentions, moral responsibility, and rational design, aiming not to accept the world as it is, but to shape it into what it ought to be.

Why does Sowell argue human nature is central to political conflict in A Conflict of Visions?

Vision, Sowell argues, is a “pre-analytic cognitive act.”

It’s what we sense or feel before we’ve constructed any systematic reasoning that could be called a theory. The key point is that theories are built on visions. That means even the definitions of concepts we debate every day can be different for different people.

This is one reason why debates about economics, freedom, free trade, justice, power, and equality seem to go on forever—sometimes for centuries.

Understanding this helps us see where each other stand on a deeper, moral level, which in turn can help resolve these long-lasting debates.

What criticisms have been made of A Conflict of Visions by Thomas Sowell?

Some critics say Sowell’s two-vision framework oversimplifies political beliefs, since most real-world views are a mix of both. Others point out that it downplays historical and social context and sometimes leans more toward the constrained vision in its examples.

Even so, the book is still useful and well respected for seeing the patterns that keep repeating in the world for centuries.

Explain the difference between the constrained vision and the unconstrained vision in A Conflict of Visions.

The constrained vision assumes that human nature is limited and self-interested. Moral progress doesn’t come from trying to fix these flaws, but from learning how to manage them. This vision puts its faith in institutions, traditions, and systems—like markets, laws, and social norms—that channel our imperfect motives toward something socially useful.

The unconstrained vision, on the other hand, starts from the belief that human nature can be improved and reach its full potential. With enough reason, education, and moral effort, social problems aren’t just manageable—they’re solvable. This view trusts in intentions, moral responsibility, and rational design, aiming not to accept the world as it is, but to shape it into what it ought to be.

How does Thomas Sowell use historical thinkers and examples to illustrate his two visions?

Sowell draws on many thinkers, politicians, and economists from the past to illustrate the two main visions discussed in the book: constrained and unconstrained.

For the constrained vision, he often quotes Adam Smith, especially from his book The Wealth of Nations. On the other hand, for the unconstrained vision, Sowell frequently references Jean-Jacques Rousseau, particularly his 1762 work, The Social Contract (Du contrat social).