Snapshot

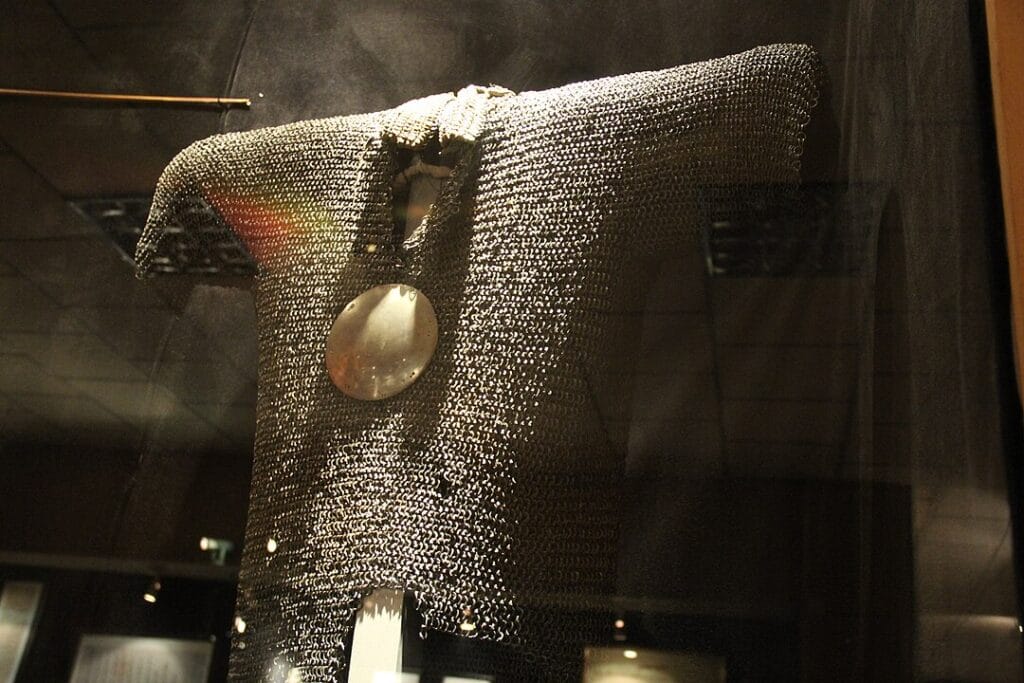

On the book, Chronica Majora(1240s–1250s), the author describes the mongol army:

“They clothe themselves in the skins of bulls, and are armed with iron lances; they are short in stature and thickset, compact in their bodies, and of great strength; invincible in battle, indefatigable in labour; they wear no armour on the back part of their bodies, but are protected by it in front; they drink the blood which flows from their flocks, and consider it a delicacy; they have large powerful horses, which eat leaves and even the trees themselves, and which owing to the shortness of their legs, they mount by three steps instead of stirrups.”

Genghis Khan by Jack Weatherford tells the remarkable story of how a troubled boy from a small tribe in Mongolia, who began with nothing, created such a disciplined and fearsome army and became one of the greatest conquerors of all time.

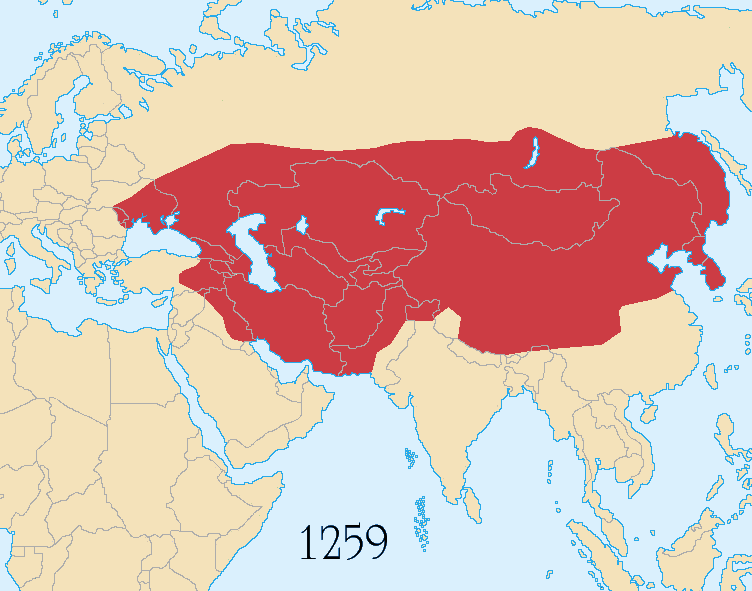

The book discusses how, in just twenty-five years, the Mongols conquered more lands and people than the Romans had conquered in four hundred years, and the impact it made on the world today.

Table of Contents

Part 1: The Reign of Terror on the Steppe: 1162–1206

The Blood Cot

In the spring of 1162, the Year of the Horse in the Asian calendar, a boy was born in a small village near the border of modern-day Mongolia and Siberia.

Little did everybody know that the boy would one day become the world’s greatest conqueror.

His mother, Hoelun, named him Temüjin.

From the very beginning, life was hard for them.

Hoelun had been kidnapped while traveling along the Onon River by a man named Yesügei, a hunter from a small clan that would later be known as the Mongols. Back then, they were just another poor, small tribe on the steppe; a vast, open territory from Central Europe to China

People say that when Temüjin was born, he was holding a small black blood clot in his hand. Some thought it was a sign of greatness, others thought it was a curse. Even today, after nearly 800 years, we still look for an answer.

When Temüjin was eight years old, his father was poisoned by a rival clan. Hoelun was left with five children to raise alone in the freezing, open land of Mongolia. Somehow, she kept them all alive.

That is a great surviving story on its own. But it also makes you wonder: how could a boy from such a poor, broken family end up ruling the largest empire in history?

The Secret History of the Mongols, an old record about his life, gives some clues from his early life. It shows that even as a kid, Temüjin cared more about trust and loyalty than blood ties. That was unusual back then because most people only trusted their family or clan.

The tragedies his family endured seemed to have instilled in him a profound determination to defy the strict caste structure of the steppes, to take charge of his fate, and to rely on alliances with trusted associates, rather than his family or tribe, as his primary base of support. (page 21)

One of his closest friends was Jamuka, a boy from another tribe. Jamuka would later become one of his strongest allies, and later, one of his biggest enemies.

But not all his family ties were that strong.

His half-brother Begter often picked on him. One day, after too many fights, Temüjin and his younger brother killed him. It was the first time Temüjin took a life, and it showed how far he was willing to go to survive.

The Tale of Three Rivers

By 1178, Temüjin was sixteen and married to his childhood fiancée, Börte.

One day, their camp was attacked by the Merkids, another tribal clan, and Börte was kidnapped.

Temüjin had two choices: run and hide or fight to get her back.

He chose to fight.

He went to two people he trusted: Ong Khan, an older and respected leader, and Jamuka, his sworn brother. Together, they formed an army and rode to rescue Börte. Ong Khan led the right side, Jamuka the left, and Temüjin took the center.

The attack worked. They defeated the Merkids and brought Börte home.

Not long after, Börte gave birth to their first son, Jochi.

After that victory, Temüjin began to move away from hunting and learned how to herd animals from Jamuka’s people. But over time, things changed. Jamuka started treating him more like a servant than an equal.

That tension grew into open conflict, a fight for power that lasted nearly twenty years.

This is the beginning of the Mongol Civil War.

By 1181, Temüjin had broken away from Jamuka completely. He started building alliances of his own, focusing on loyalty and fairness.

Temüjin’s discipline and his sense of ‘order’ made him unique from other tribal chiefs.

He organized his warriors into squads, or arban, of ten who were to be brothers to one another. No matter what their kin group or tribal origin, they were ordered to live and fight together as loyally as brothers; in the ultimate affirmation of kinship, no one of them could ever leave the other behind in battle as a captive. Like any family of brothers in which the eldest had total control, the eldest man took the leadership position in the Mongol army, but the men could also choose another to hold this position. (page 52)

By his early thirties, he had defeated some of the most powerful tribes on the steppe: the Tatars, Tayichiud, and Jurkin.

But one big fight still remained: the final battle against Jamuka.

War of Khans

That last battle came in 1204, the Year of the Rat.

Temüjin used a clever trick. His soldiers carried bushes and branches in front of them to make the army look much larger than it was. This “moving bush” strategy scared Jamuka’s men before the battle even began.

When the fighting started, Temüjin’s army moved fast and hit hard. Jamuka’s forces quickly fell apart. His own men, desperate to save themselves, betrayed him and handed him over to Temüjin.

Jamuka was executed.

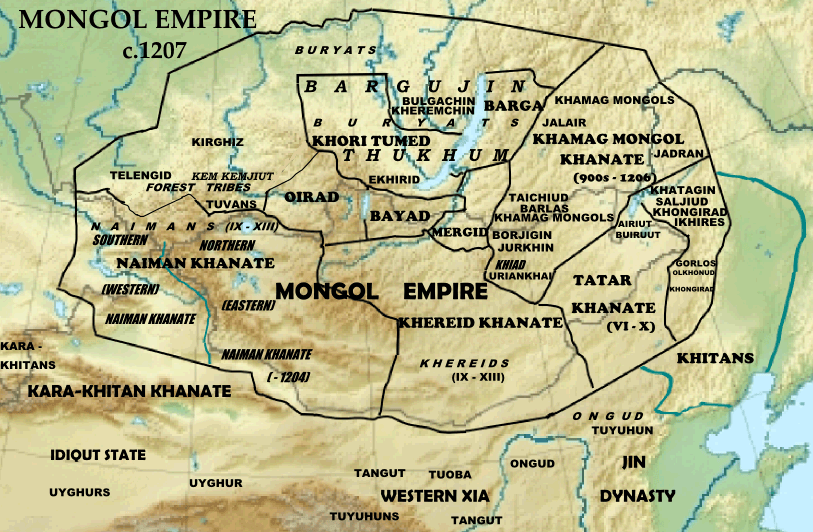

With that battle ended, Temüjin became the sole ruler of the entire Mongolian steppe, a land as large as Western Europe.

Now that he rules the entire Steppe, he wants to make sure it stays that way going forward.

To stop the further tribal fighting, he created a set of laws called The Great Law (Yassa) and built a central government where people were chosen by skill and loyalty, not by birth.

In later life, he would judge others primarily by their actions toward him and not according to their kinship bonds, a revolutionary concept in steppe society. (page 26)

From a world of small, fighting clans, a single nation was born. And Temüjin took a new name: Genghis Khan, meaning “Universal Ruler.”

Part 2: The Mongol World War (1211–1261)

Spitting on the Golden Khan

Now, he looked to south, toward the Jin dynasty in northern China, a powerful empire that had once demanded taxes from the Mongols.

When Genghis Khan sent his messengers, the Jin emperor insulted them.

That led to war.

In 1211, he led his army across the Great Wall of China. At this time, Genghis Khan’s army had years of experience in warfare. Some of the techniques they were using were novel and oblivious to the enemy.

After all the reconnaissance, organization, and propaganda, when the attack finally came, the Mongol army sought to create as much confusion and havoc for the enemy as possible. One of the most common forms of attack, similar to the Bush Formation, was the Crow Swarm or Falling Stars attack. At the signal of a drum, or by fire at night, the horsemen came galloping from all directions at once. In the words of a Chinese observer of the time, “they come as though the sky were falling, and they disappear like the flash of lightning.” The enemy was shaken and unnerved by the sudden assault and equally sudden disappearance, the roaring wave of noise followed by a greater silence. Before they could respond properly to the attack, the Mongols were gone and left the enemy bleeding and confused. (page 94)

When he could not overtake their fortifications, Genghis Khan tried to draw the enemy out from their stronghold through strategems such as pretending to retreat, as illustrated in Jebe’s siege of Liaoyang during the Jurchen campaign. In a movement known as the Dog Fight tactic, he feigned a withdrawal, ordering his troops to leave behind a lot of their equipment and stores as though they had fled in great fearful haste. The city officials sent soldiers out to gather up the booty, and they quickly clogged the open gates with carts and animals transporting all the goods. With the soldiers on the open field, and the city gates opened, the Mongols fell upon them and raced through the open doors to capture the city. (page 95)

Cities that didn’t give up were destroyed. Those who surrendered were spared.

By 1215, the Mongols had captured Zhongdu; today’s Beijing.

A new world power had arrived.

Sultan Versus Khan

After China, Genghis Khan turned west toward the Khwarazm Empire, a rich Islamic kingdom covering much of Persia and Central Asia.

Genghis Khan sent envoys. Their choices were two-fold. Either they have to surrender or prepare for war.

When the Shah of Khwarazm killed Genghis’s envoys, it became personal.

Genghis launched one of the most devastating attacks in history against the Khwarazm Empire.

His army surrounded Shah’s kingdom, divided into smaller groups while keeping their communications intact across thousands of miles.

To ensure accurate memorization, the officers composed their orders in rhyme, using a standardized system known to every soldier. The Mongol warriors used a set of fixed melodies and poetic styles into which various words could be improvised according to the meaning of the message. For a soldier, hearing the message was like learning a new verse to a song that he already knew. (page 88)

They crushed great cities like Bukhara and Samarkand. By 1221, the Khwarazm Empire was completely destroyed.

The Mongols now ruled from the Pacific Ocean to the Caspian Sea.

The Discovery and Conquest of Europe

After Genghis’s death, his sons and generals kept expanding.

The momentum Genghis Khan built was enough for them to conquer the rest of Europe.

By the late 1230s, Mongol armies had reached Russia, Hungary, and Poland.

Europe, divided and unprepared, and confused by the Mongols’ bizarre war tactics, thought they were ‘being attacked by monsters’.

Then, just as suddenly as they came, the Mongols left after the death of Ögedei Khan, Genghis Khan’s son.

But their brief arrival changed Europe forever.

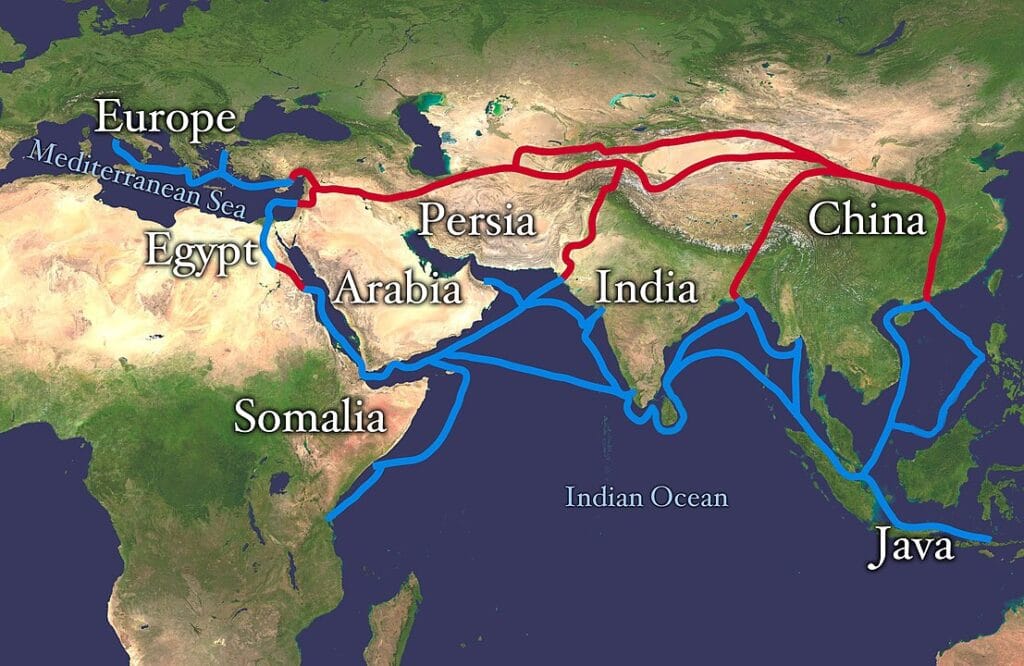

For the first time, Europeans saw the vast world beyond their borders. It opened the door to new trade, travel, and cultural exchange — laying the path for the Silk Road that would link East and West.

Warring Queens

When Genghis Khan died in 1227, his sons were barely holding the empire together.

Besides, they were busy conquering the European regions.

But the Mongol empire didn’t fall apart, and that was thanks to the Mongol queens.

Women like Töregene Khatun and Sorghaghtani Beki ruled territories, handled politics, and kept the empire together while their sons and husbands were at war.

Weatherford calls this the “hidden matriarchy”, the unseen network of women who helped build and protect one of the largest empires in history.

Part 3: The Global Awakening (1262–1962)

Khubilai Khan and the New Mongol Empire

Among Genghis Khan’s grandchildren, Khubilai Khan was the one who stood out.

He was both a warrior and a statesman. His war tactics made him an outlier among other Mongol warriors.

He finished the conquest of China and started the Yuan Dynasty, ruling from a new capital in what is now Beijing.

Khubilai respected Chinese culture and mixed it with Mongol traditions. He encouraged trade, science, and learning. Scholars, artists, and travelers, including Marco Polo, came from all over the world to his court.

After Genghis Khan, who conquered a massive land, Khubilai Khan took the next step, making those lands sustainable.

Under Khubilai, the Mongol Empire became the center of global connection.

Their Golden Light

The time that followed, known as the Pax Mongolica, or “Mongol Peace” — was a golden age of global exchange.

For the first time in history, most of Eurasia was connected by trade and communication.

Paper money, printing, gunpowder, and new navigation tools spread across continents.

The Mongols even created a postal system—the Yam—that allowed messages to travel quickly across thousands of miles.

This era became the bridge between the old world and the modern one; between isolation and globalization.

The Empire Illusion

In the last part of the book, Weatherford looks at how history later painted the Mongols unfairly.

Western writers often called Genghis Khan a barbarian, forgetting that he also built systems of trade, law, and merit-based leadership.

In truth, many systems we use today—like government bureaucracy, free trade, and promotions based on skill—began with the Mongols.

By 1962, on the 800th anniversary of Genghis’s birth, Mongolia had reclaimed its identity and history.

Ideas that resonate with me

Mongol army tactics were horrifying, as they were effective in warfare

Mongol warriors had a thick frontal armour and almost nothing for the back armour. That means, if they try to run away from the enemies, they are as good as dead. So, in a battle, they only had two options: either to fight until conclusion or walk away, that is, to die.

Matthew Paris (c. 1200–1259), an English Benedictine monk mentions this in his book, Chronica Majora:

‘They wear no armour on the back part of their bodies, but are protected by it in front’

Mongols had only one goal

One thing that stood out to me is that Genghis Khan was always improving his warfare strategies, but nothing else.

Weatherford mentions that, unlike other conquerors, the Mongols didn’t develop anything else; no cities, no arts, even though they were the first to kickstart global trade. They just poured all their time into getting better at fighting.

The Mongols had changed the formula of gunpowder to provide enough oxygen to make it ignite in one rapid blast rather than in the traditional slow burn of the firelance or of rockets. Such instantaneous burning produced an explosion rather than a fire, and the Mongols harnessed these explosions to hurl a variety of projectiles. Craftsmen made some of the tubes small enough that a single man could operate them and thus fire out arrowheads or other metal projectiles. The explosion in these tubes required a stronger material than bamboo; so they were made with iron tubes. The Mongols attached the smaller tubes to a wooden handle for ease of handling, and they mounted the larger ones on wheels for ease of mobility. Larger tubes fired ceramic or metal cases filled with shrapnel or more gunpowder that produced a secondary explosion upon impact. In their assault, the Mongols combined all of these forms of bombardment in an assortment of smoke bombs, proto-grenades, simple forms of mortars, and incendiary rockets. They had developed explosive devices able to hurl projectiles with such force that they may as well have been using real cannons; they managed to concentrate their fire on one area of the city defenses and hammer it down. (page 182)

This strategy worked both ways.

On one side, it made them extremely good at warfare; so good that they seemed invincible. On the flip side, it meant they always had to rely on war. Without the supplies from the empires they conquered, they couldn’t survive.

The more they conquered, the more they needed to conquer.

Death and burial of Genghis Khan

The burial site of Genghis Khan is still one of history’s great mysteries. Before his death, he reportedly said, “Let my body go, let my nation live,” and chose to be buried in an unmarked grave. After he died in 1227, legend has it that there was a massive burial ceremony, and yet his burial site is not disclosed.

William Honeychurch, an associate professor of anthropology at Yale, speculates that Genghis Khan’s tomb might be somewhere in the mountains of Khentii Province in Mongolia. Nancy Steinhardt, a professor of East Asian art at the University of Pennsylvania, told Live Science in an email, “I don’t think it will be found any time soon.”

Jack Weatherford, the author of Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World, adds another layer to the mystery. In an interview, he said that while the location is known among Mongols, people of Mongolia would never disclose it to the public. For them, his burial site is sacred.

Parts that left a mark on me

History has condemned most conquerors to miserable, untimely deaths. At age thirty-three, Alexander the Great died under mysterious circumstances in Babylon, while his followers killed off his family and carved up his lands. Julius Caesar’s fellow aristocrats and former allies stabbed him to death in the chamber of the Roman Senate. After enduring the destruction and reversal of all his conquests, a lonely and embittered Napoleon faced death as a solitary prisoner on one of the most remote and inaccessible islands on the planet. The nearly seventy-year-old Genghis Khan, however, passed away in his camp bed, surrounded by a loving family, faithful friends, and loyal soldiers ready to risk their life at his command. (page xx)

After all the reconnaissance, organization, and propaganda, when the attack finally came, the Mongol army sought to create as much confusion and havoc for the enemy as possible. One of the most common forms of attack, similar to the Bush Formation, was the Crow Swarm or Falling Stars attack. At the signal of a drum, or by fire at night, the horsemen came galloping from all directions at once. In the words of a Chinese observer of the time, “they come as though the sky were falling, and they disappear like the flash of lightning.” The enemy was shaken and unnerved by the sudden assault and equally sudden disappearance, the roaring wave of noise followed by a greater silence. Before they could respond properly to the attack, the Mongols were gone and left the enemy bleeding and confused. (page 94)

The majority of people today live in countries conquered by the Mongols; on the modern map, Genghis Kahn’s conquests include thirty countries with well over 3 billion people. The most astonishing aspect of this achievement is that the entire Mongol tribe under him numbered around a million, smaller than the workforce of some modern corporations. From this million, he recruited his army, which was comprised of no more than one hundred thousand warriors—a group that could comfortably fit into the larger sports stadiums of the modern era. (page xviii)

How did the book change the way I think?

To get really good at something, you have to immerse yourself in just one thing—and only that thing—for a very long time.

Genghis Khan did exactly that.

He poured all his time, energy, and resources into warfare. Nothing else. This single-minded focus is what made him, in his time and for all time, the greatest conqueror in history.

Coffee chat

What is the ‘secret history’ that Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World always refers to?

The Secret History is an ancient Mongol document, written in the Mongolian language sometime after Genghis Khan’s death in 1227. In Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World, Jack Weatherford consistently refers to it as the primary source for Genghis Khan’s early life.

What is the thesis of Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World?

The primary thesis of Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World is: for better or worse, for good or bad, Genghis Khan and his empire left a huge mark on the world we live in today.

How did Genghis Khan shape the modern world?

Some of the political, economic, and social initiatives that Genghis Khan started are still influencing the world today.

His empire stretched from Korea to Eastern Europe, and for the first time in history, the entire Eurasian continent was united under a single political entity. This was the first step toward economic globalization. The unified system opened doors to trade, established the Silk Road for merchants, and introduced paper currency in China, which encouraged credit-based systems.

Genghis Khan’s political approach was revolutionary for its time. He promoted people based on talent and performance, not lineage. This was a radical step in politics back then. He also tolerated all religions, allowing diverse beliefs to coexist within his empire. After uniting Eurasia, the Mongols made a huge effort to connect scholars, artisans, and scientists from Persia, China, and the Islamic world, sparking a technological and cultural awakening that resonated far beyond their era.

Why is Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World so popular?

The book is extremely well written.

Even if you just read the topic sentences of each paragraph, which you could do in 30 minutes to an hour, you’ll still come away with a surprisingly extensive knowledge of Genghis Khan and his empire.

On top of that, Jack Weatherford’s thorough research, paired with his epic narrative, hooks you from cover to cover.

What criticisms exist of Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World?

The narration isn’t neutral.

Jack Weatherford portrays Genghis Khan as a champion of meritocracy, religious tolerance, and even women’s rights. He has enough sources to back this up, but there’s a risk of over-romanticizing. After all, he was also one of the most violent conquerors the world has ever seen.

That said, Weatherford doesn’t hide Genghis Khan’s brutal methods or his use of violence.

What are the key contributions of Jack Weatherford’s Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World?

This book gives a ‘concise overview’ of how Genghis Khan rose to power. The book is best as the first book for someone to learn about the Mongol empire.

Summarize Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World in 3 paragraphs

The first part of the book tells the story of Genghis Khan’s rise to power on the steppe, exploring the forces that shaped his life and personality from his birth in 1162 until he unified all the tribes and founded the Mongol nation in 1206.

The second part follows the Mongols’ entrance onto the stage of history through the Mongol World War, which lasted five decades—from 1211 to 1261—until Genghis Khan’s grandsons turned against one another.

The third section examines the century of peace and the Global Awakening that laid the foundations for the political, commercial, and military institutions of the modern world.

What sources did Weatherford use to write the book?

One of the main sources for this book is ‘Secret History’.

The Secret History is an ancient Mongol document, written in the Mongolian language sometime after Genghis Khan’s death in 1227. In Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World, Jack Weatherford consistently refers to it as the primary source for Genghis Khan’s early life.

“Our team began working together. We compared the most important primary and secondary texts from a dozen languages with the accounts in the Secret History. We hunched over maps and debated the precise meaning of different documents and much older analyses. Not surprisingly, we found vast discrepancies and numerous contradictions that were difficult to reconcile.” (page xxxi)

Was Genghis Khan unusually brutal for his time?

Yes, Genghis Khan’s war tactics were rooted in violence, even though he brought peace once he rose to supreme power.

“While the destruction of many cities was complete, the numbers given by historians over the years were not merely exaggerated or fanciful—they were preposterous. The Persian chronicles reported that at the battle of Nishapur, the Mongols slaughtered the staggeringly precise number of 1,747,000. This surpassed the 1,600,000 listed as executed in the city of Herat. In more outrageous claims, Juzjani, a respectable but vehemently anti-Mongol historian, puts the total for Herat at 2,400,000. Later, more conservative scholars place the number of dead from Genghis Khan’s invasion of central Asia at 15 million within five years. Even this more modest total, however, would require that each Mongol kill more than a hundred people; the inflated tallies for other cities required a slaughter of 350 people by every Mongol soldier. Had so many people lived in the cities of central Asia at the time, they could have easily overwhelmed the invading Mongols.” (page 118)

How did Genghis Khan treat religion and religious freedom?

Genghis Khan’s core belief was that, no matter what religion we follow or worship, we are all honoring the same ultimate reality.

In The Secret History, he says, “We believe that there is only one Eternal Heaven. We honor the gods of all men, and we wish that they grant us their aid.” As a result, he allowed anyone under his empire to practice whichever religion they wanted, a radical decision for that time.

Jack Weatherford even wrote a separate book on Genghis Khan’s approach to religious freedom, Genghis Khan and the Quest for God.

What was Genghis Khan like before he became “Khan”?

Temüjin(Genghis Khan’s birth name) didn’t have an easy childhood.

At a very young age, he lost his father, and his mother, Hoelun, had to raise five children in the wilderness with almost no supplies. Even so, from an early age, Temüjin showed the qualities of a future emperor. He built alliances outside his clan, which was unusual for someone to do at that time.

These allies would later help him enormously in creating the Mongol Empire.

Is this book a good introduction to Mongol history?

Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World is the best beginner’s book for learning about the rise of modern empires. It provides a trustworthy and concise summary of the entire Mongol Empire, from Genghis Khan’s early life to the era of his grandchildren.

On top of that, the book is extremely well written, which makes it an easy and engaging read.