20 years ago, I remember going to this small, two-room library my dad once introduced me to.

I would spend my summer holidays reading books, as if reading was my day job.

For three months straight, I’d eat breakfast, pack my lunch, and head to that library, only to return home past six in the evening. I followed that same routine every summer and every December break for six years, and by the end of it, I had probably read eighty percent of all the books on those shelves.

That’s a lot of books.

But more importantly, I remember everything I read during those six years.

But that was when I was a kid. And then, life got complicated.

When I tried getting back into reading in my twenties, I sometimes couldn’t even recall what was in the book I’d finished just the day before. Once I started working, it got worse. I could hardly remember anything at all.

Life got busy too quickly.

I still loved reading, but at some point I began to wonder: what’s the point of reading if you can’t remember a thing?

If one person reads a single book a month but has a framework to reflect on and remember what they’ve read, and another rushes through four books just to say they’ve finished them, who’s likely to make better decisions in life ten years from now?

Probably the one who reads to learn, not the one who reads to finish.

But building such a framework isn’t that straightforward.

How do we read and actually remember what we read while juggling everything else; jobs, routines, endless distractions?

Sure, there’s plenty of advice out there. But that, strangely enough, was the problem for me. So I had to dig down to the root of it and come up with a framework that’s simple, practical, and works over time.

This framework lets me read 50+ books a year while working full time, and helped me remember, what I want to remember, from each and every one them.

Table of Contents

Part 1: Why most systems fail?

The wrong system always creates fatigue.

This is true for anything, whether it’s a system for remembering what you read or managing something entirely different.

But it’s worth asking why.

Some years ago, I tried the Zettelkasten system to help me remember what I read. I’d heard that authors like Robert Greene and Ryan Holiday use it, and since it had stood the test of time, I was convinced it was the right choice. Instead of the original paper version, I recreated it inside my note-taking app, Obsidian.

The first few weeks were exciting.

I spent hours deciding how to categorize everything I read, and after finishing each book, I would carefully file my notes into their respective folders.

But all that excitement faded after a few months.

The more time I spent with this system, the more fatigue it created.

After about six months of dragging myself through a process that clearly wasn’t working, I quit. That failure hit harder than I expected. For a while, I couldn’t even bring myself to read again at all.

Later, I asked myself why. Why had this brilliant system failed me when it worked for so many writers?

Then it became clear. The answer was already in the question.

They’re writers. Reading is a part of their job. Of course, they can make a system like that function smoothly. It’s built for people whose days revolve around reading, writing, and refining ideas. For them, the complexity of this system isn’t a burden; it’s what makes their life easier.

But for someone like me, someone with a full-time job who still wants to read and remember. It’s quite the opposite.

Some systems look perfect on paper but collapse in real life. Even if you push through, they quietly build fatigue until, one day, you burn out and stop reading altogether.

For most of us, probably ninety-nine percent of those looking for a “system to remember what we read”, reading is something we fit around work, family, and limited energy.

That means we need to start small and be practical.

This is why, after nearly a decade of trial and error, I developed a framework that works well within a busy life.

The framework below is a ‘barebones’ system: simple enough for anyone to start with, yet flexible enough to customize it over time.

Part 2: The Framework

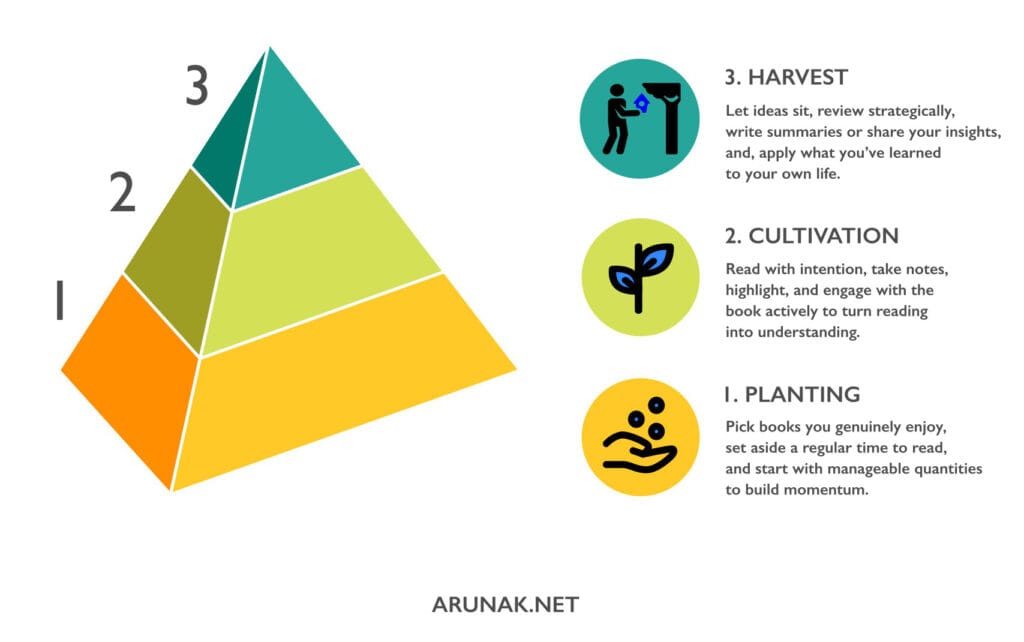

Step 1: Planting

Select a book that you would enjoy

If I had to answer the question, “How do you remember what you read?” in one sentence, it would be this: read what you actually like.

Everything else on this framework depends on this.

Think of reading as a tree growing toward light.

A tree doesn’t argue with where the sunlight should be. It follows it. Reading works the same way. When you keep chasing what everyone else is reading, forcing yourself toward books that don’t genuinely interest you, fatigue builds quietly. You might still turn the pages, but nothing will stay with you. And soon, even reading itself begins to feel like work.

But when you start with what draws you in, growth happens organically. One book points to another; your curiosity expands on its own. Without effort, you find yourself picking up harder, deeper books because now you are actually interested in them.

That’s when reading becomes a living, breathing process, not an obligation. We should not force it.

So don’t start with a book that has 1000 pages and takes 10 minutes to grasp one page’s information. Start small. Pick the short one, the hundred-page book, written in clear, simple language, that you can finish in a few days.

The momentum of finishing matters more than the difficulty of the book.

Because you won’t remember much from a book you never enjoyed, even if it’s “good for you.”

Pick a time to read every day

If you don’t read, there’s nothing to remember in the first place!

That’s why it’s important to set aside a time to read. Life is busy already; without a dedicated slot, reading slips into the category of “optional”. And optional habits never last.

But this isn’t just about consistency; it’s also about memory. The times you choose to read also matter. If you choose to read right after work or during your commute, you are surrounded by distractions. You might turn the pages, but nothing will stick. That’s fine for a light novel, but if you’re reading non-fiction and want the ideas to stay, you need a quiet place to focus on what you read.

Even the smallest things count. Reading when you’re tired or hungry is a common trap.

A good start is to fix a time daily, say an hour, just for reading. Later, you can add a rough page target. Some books will demand slow reading; others will flow faster. Over time, you’ll sense the rhythm of each.

Here’s why a page target matters: imagine reading for half an hour at night, distracted. You move through five pages and close the book, thinking you’ve done your part. But have you really? If that pattern repeats, the reading habit fades quietly.

Reading more also means remembering more. A small page goal keeps you honest and keeps you up to date with progress.

An argument can be made, “Isn’t the goal to remember, not just to finish?”

Not quite.

Most non-fiction books, for example, are built around one main idea. You can’t see the whole picture halfway through. Finishing the book gives you context, and only then can you revisit and reflect on what really matters. It’s way more effective to focus on remembering things after you know the full story, instead of trying to do it with just half the picture (see Step 3 of this framework).

There’s another advantage: finishing books builds momentum. Each completion fuels the next, and with it, your capacity to remember deepens.

I learned this the hard way. I used to listen to audiobooks while working, and almost nothing stayed. My attention was split; the words became background noise. Reading, if you mean to retain it, cannot be background noise. It needs its own time and its own attention.

Pick a time and stick with it for a while. If it doesn’t fit, adjust it. Mornings often work best because the mind is clear and open.

When I was building the habit, I read at the very start and very end of the day. Both worked fine at first. But then I noticed that my mind is in totally different states in the morning and evening, even though it feels “peaceful” at both times. In the morning, the day is just starting, and the mind is ready for a challenge. In the evening, right before bed, it doesn’t want that heavy work; it’s winding down. So a tough non-fiction book works well in the morning, but not at night. That’s when I realized I should read at least two books at a time.

Read more than one book at a time

Reading is like a diet. It’s best to pair a slow-cooked stew with a crisp salad or a rich slice of cake with tea. Balance matters. A dense, demanding book gives substance and nourishment; a lighter one keeps your appetite alive. Together, reading becomes a pleasure, not a chore.

But too much can backfire.

Years ago, I tried juggling five or six books at once. More books, the better, I thought. But keeping up with all that information didn’t work. Most remembering happens unconsciously (see Step 3 of this framework), and my brain wasn’t happy trying to cram six completely different ideas at once.

I settled on three. One non-fiction in the morning, one fiction at night, and a third to pick up whenever I have free time.

Step 2: Cultivation

Set a specific goal

Regardless of whether it’s a fiction or non-fiction, you would pick a book to get something out of it. If it’s a novel, it could be the pleasure of exposing yourself to a good story. If it’s a non-fiction, it could be a question that you were always thinking about and you needed a comprehensive answer, or you are trying to learn how to control your money.

It’s important to have that goal in mind before you start. This is especially important if it’s a non-fiction book.

If you are reading a non-fiction book from cover to cover, you are doing it wrong.

Once you find that answer, you can stop reading because you’ve got what you wanted.

For example, one question that’s always been in the back of my mind is: how come Asians, despite being the center of power for centuries, couldn’t hold on to it in the 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries? How did that power shift to Europe and then, relatively quickly, to the United States?

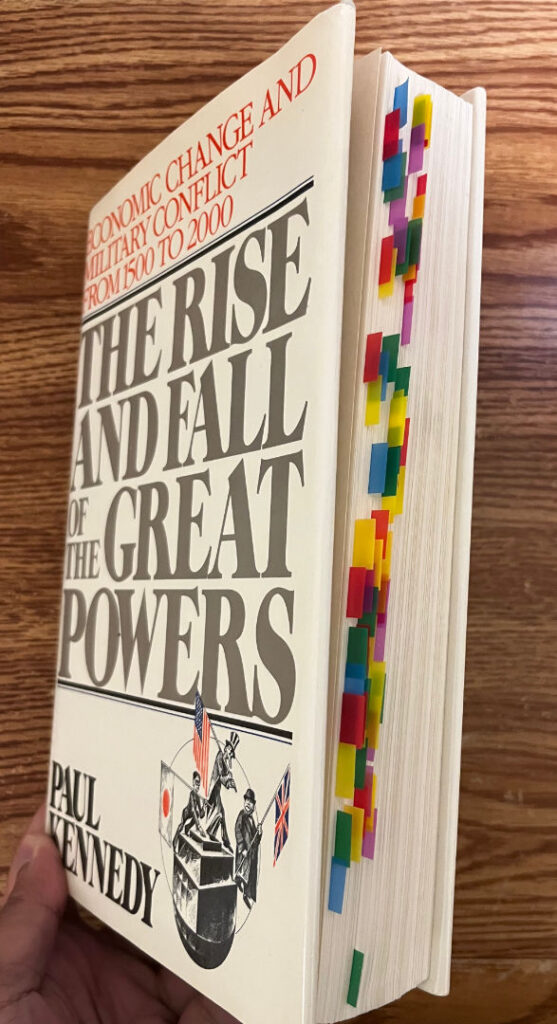

So I picked up the book, ‘The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers by Paul Kennedy‘.

I made notes, highlighted, and set bookmarks.

About halfway through this book, I found the answer. So I stopped reading.

You can see below that all the highlights end at the halfway point.

This way, you read on purpose and make sure you remember the ideas that matter most to you.

Bring the book to life

Just reading a book doesn’t mean you’ll remember it. Speed reading, listening to audiobooks (if it’s non-fiction), or rushing just to “finish” doesn’t help much in the long run.

So how can we get the most out of a book?

One way is to bring the book to life.

We rarely remember every paragraph we read last month, but we do remember small, vivid details from years ago, like the color of a friend’s car mentioned at a dinner long ago.

Why is that?

Because we were having a conversation.

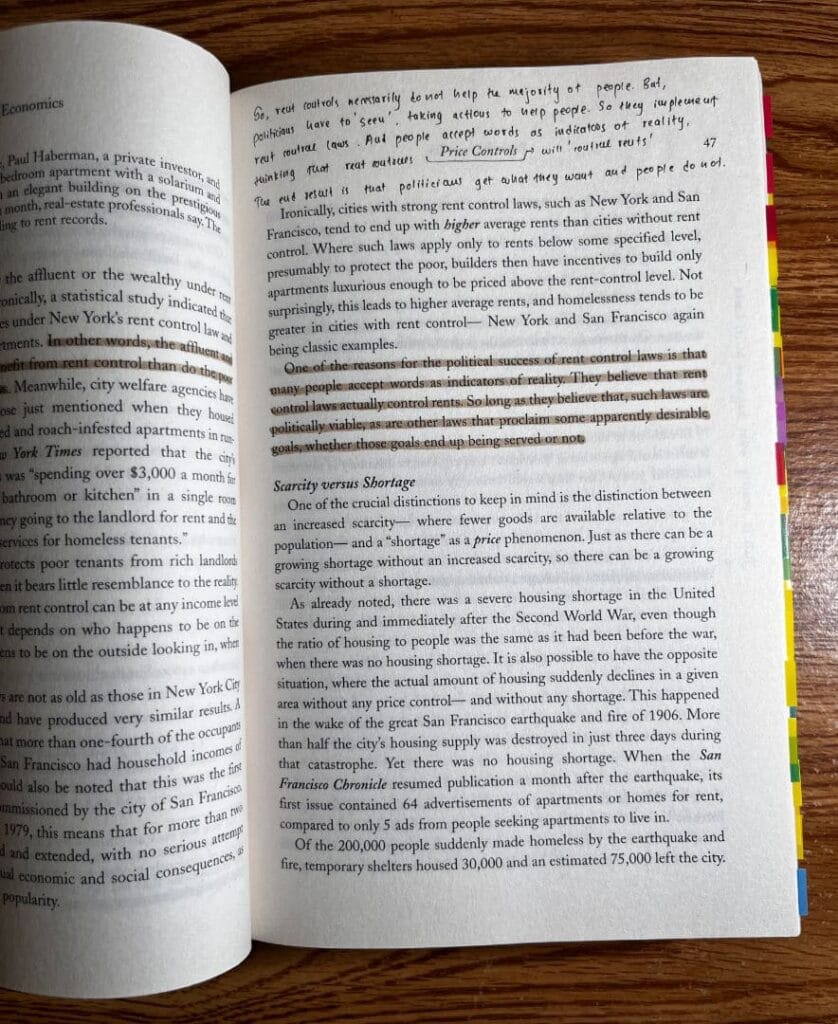

We can apply this to reading. Let the author make their point, but make yours too. Disagree when it feels right.

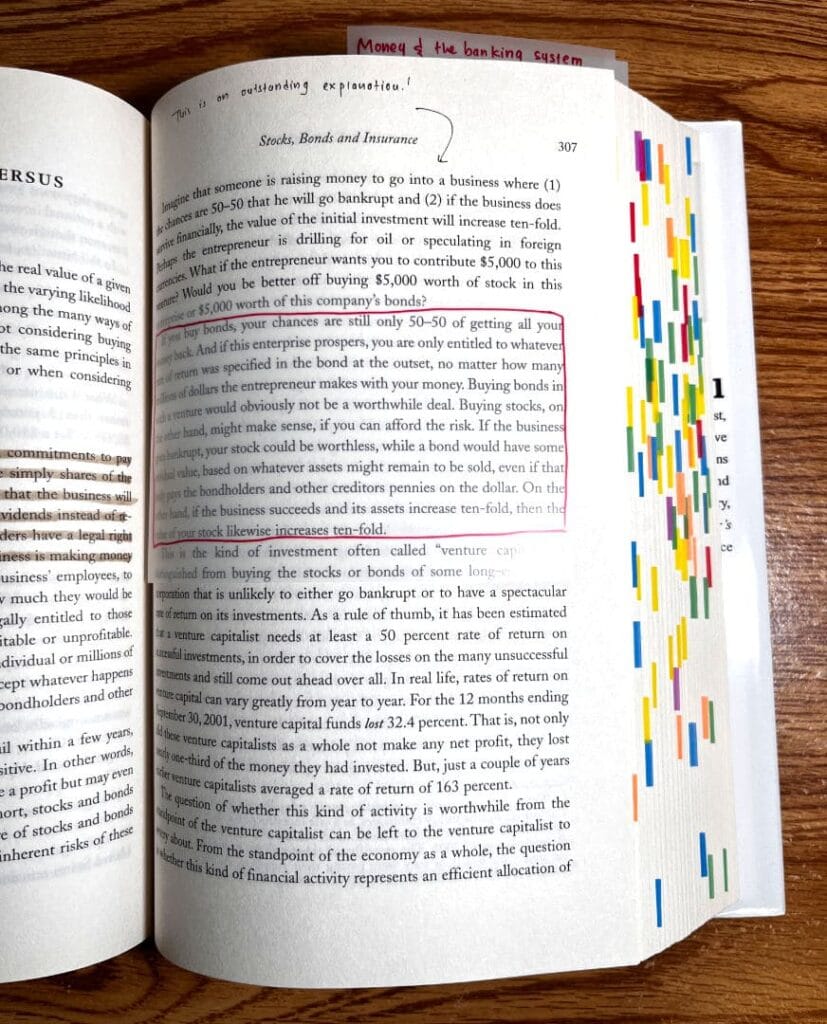

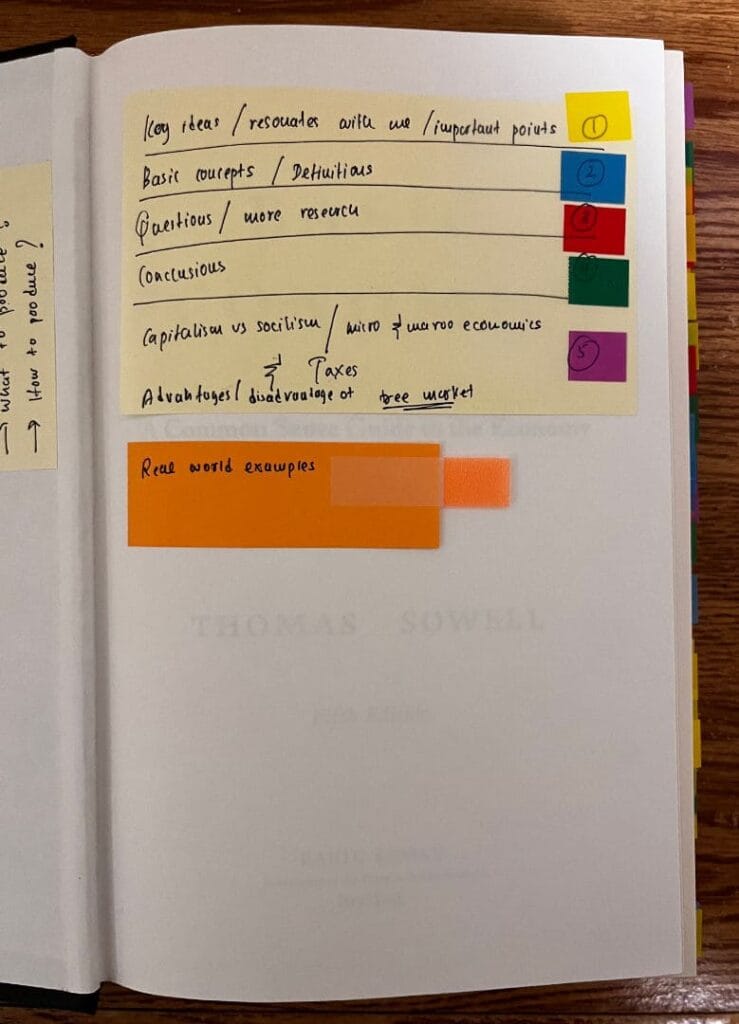

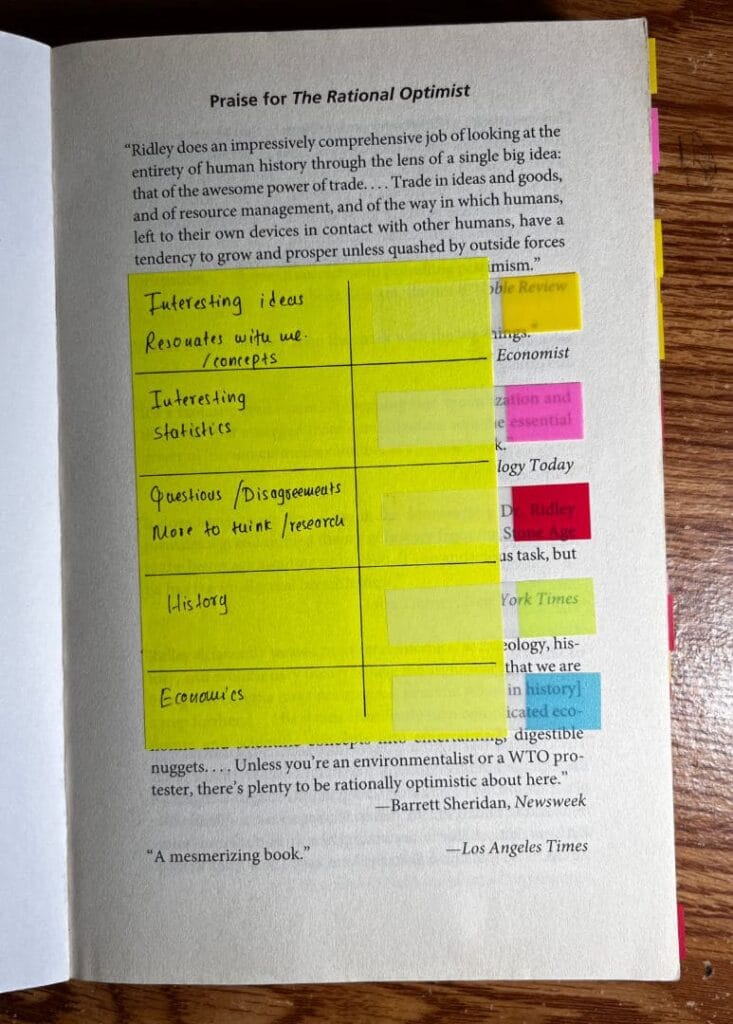

There are two ways to do this: (1) make notes, and (2) highlight and create tabs.

Some people don’t want to write in a book. Maybe they plan to return it, or it belongs to a library. In that case, you can still use sticky tabs or transparent sticky notes to mark the place and jot a note. Later, you can remove them after reflecting on your notes as a whole.

Highlighting is simple but powerful. It does two things: first, it marks a spot for your future self to return to. Second, deciding what to highlight forces you to pause, reread, and think about what really matters. These small moments add up and make a memory stick.

Highlighting becomes even more useful if you read with purpose. You highlight passages for a reason, not just because they seem interesting.

Over time, this becomes second nature. You don’t even need to check the book again to remember the points you highlighted.

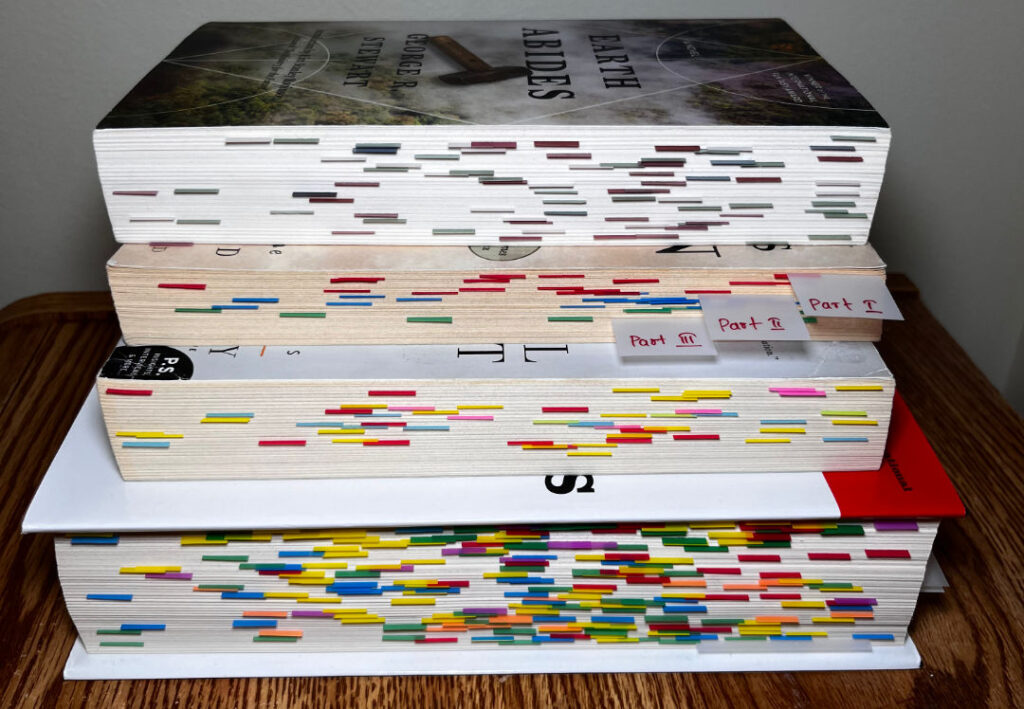

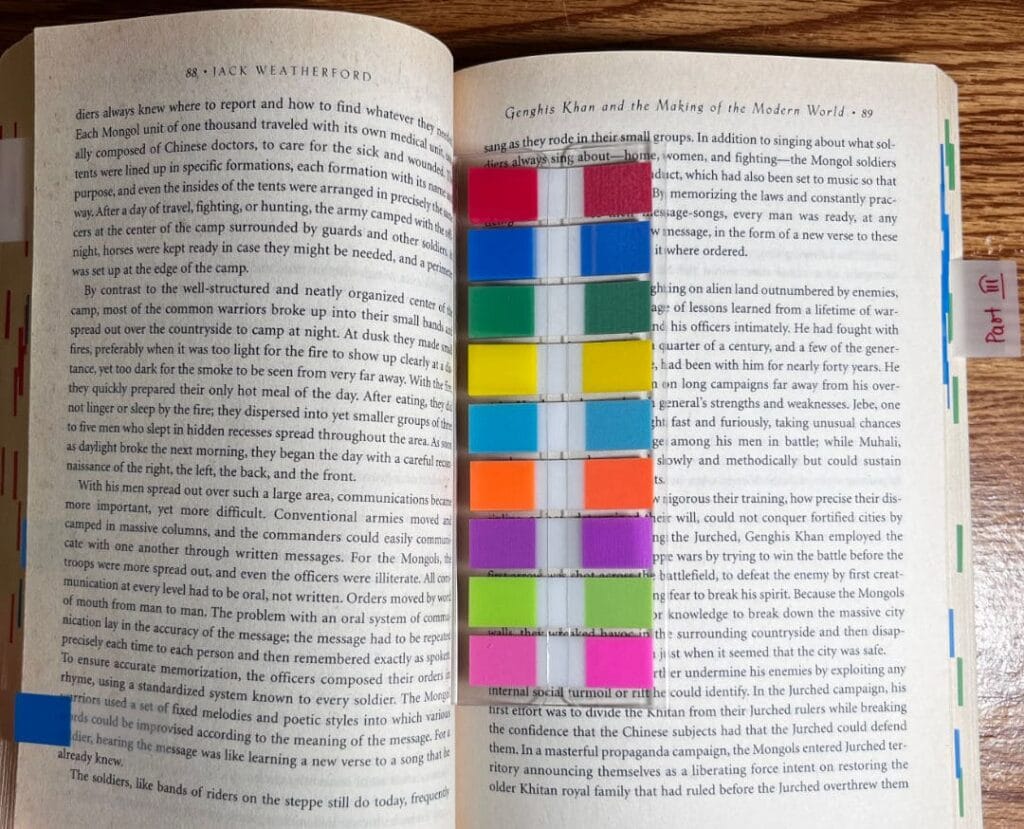

Color coding adds another layer. Different colors can show themes, ideas, or importance. Whether it’s a digital book or a physical one, collecting highlights for later review strengthens your memory.

Eventually, taking notes turns reading into understanding, into a conversation with the book. Putting ideas into your own words forces you to think, organize, and remember.

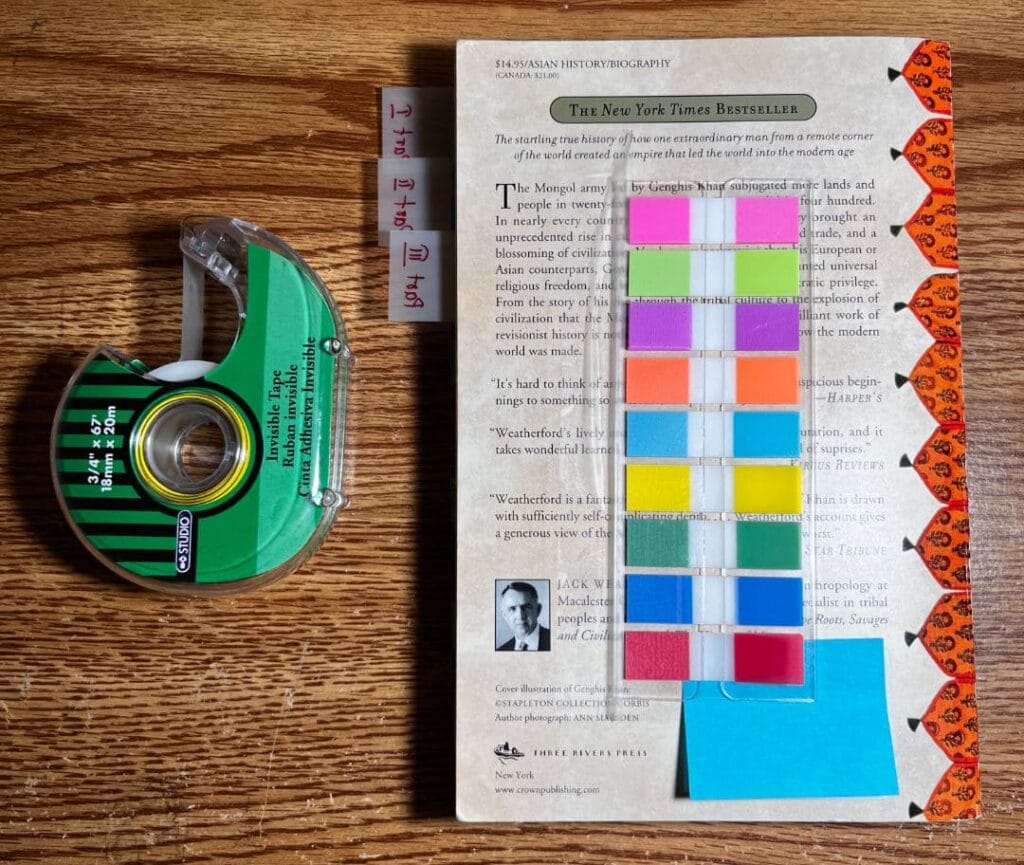

Below is a list of the items I use for color-coding, highlighting, and note-taking

- Highlight: Tombow Dual Brush Pen

- Pen: Pentel Arts Hybrid Technica 0.3 mm Pen

- Transparent sticky notes: Tekunao Transparent notes

- Sticky tabs: Moinkerin Transparent Sticky Notes

- Invisible tape: Scotch Magic Tape

Step 3: Harvest

Let it sit for a while

Most remembering actually happens without us even noticing.

There’s a reason we catch ourselves thinking about complex ideas while showering, walking, or standing in line. It’s not random. A 2024 study in PNAS Nexus found that these little mind wanderings help our brains replay and lock in memories. When you find yourself thinking about a story or an idea from a book, your brain is quietly doing its work.

But this would not happen if we force ourselves to read something that we have no interest in. This is why picking a book you actually like is the most important step in the whole framework.

If you want a book to stick for a long time, give it some breathing room. Let it sit for about a week before picking it up again and going through your notes and highlights. That pause gives your mind time to consolidate what you read, turning quick impressions into something more lasting.

After a few days, check your notes and highlights, and once more after about a month. Research on the spacing effect shows that spacing out reviews like this actually makes what you remember stronger. It’s those pauses, not just repetition, that help the book stick.

Writing a review or a summary

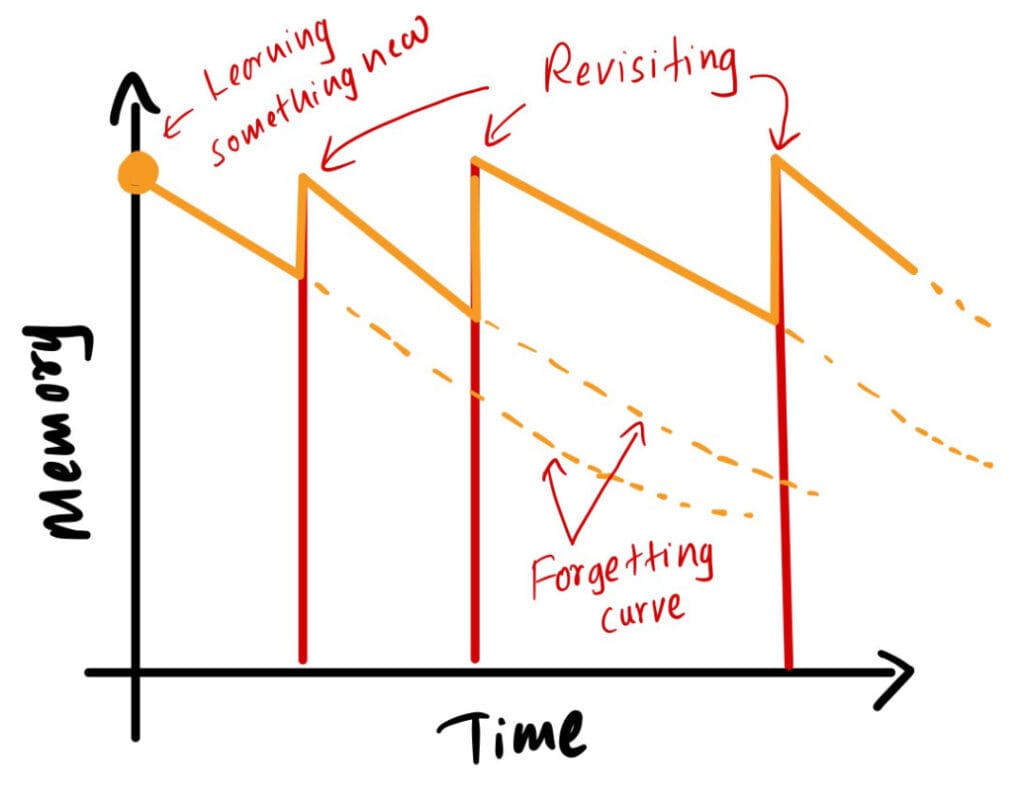

But there’s something else you might have noticed on that graph: the forgetting curve.

Even if we revisit our notes and highlights, we’re still going to forget things we learned eventually.

So how do we combat this forgetting curve?

The best way is to make something your own from those notes and highlights.

There are plenty of ways to do this: write a review, make a book summary, post a short Instagram video, even a YouTube clip—anything that makes you actively process what you read.

In other words: hold yourself accountable. Show your work. Don’t just write a summary, share it.

The easiest way to do this is to keep a record of your books, thoughts, and reflections on a social space like Goodreads or Medium. If you want to go a bit further, start a blog. There are free options, or if you want your own little corner of the internet, you can get a simple website with your own domain.

Apply it to your life

At this point, we’ve done most of the work. We should be able to remember what we read for quite a while. But how do we make this knowledge permanent?

The best way is to apply what you’ve learned.

When you apply something you learn from a book, two things happen:

- You’ll remember it for the longest time, maybe even for life. That’s the ultimate goal.

- You complete the circle. Once you’ve applied it, you’re ready to pass that knowledge on to someone else, confidently, because you’ve actually lived it.

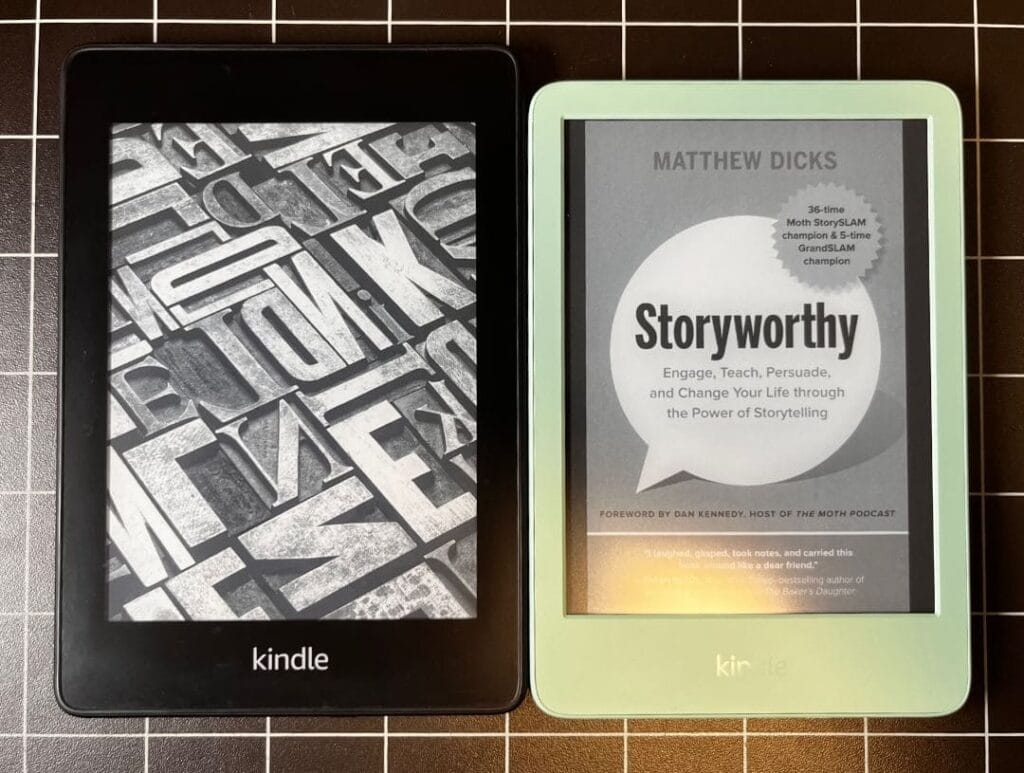

For example, about three years ago, I read Storyworthy by Matthew Dicks. The book was packed with useful, interesting ideas. But now, three years later, I only remember a handful of those ideas. One thing I remember is that Matthew Dicks made a big point about journaling. Just a few sentences a day about your thoughts or your day. He calls it “homework for life.”

I started doing it. Just a couple of sentences each day. Three years later, I’m seeing the benefits. And also, it gives me a reason to go back to the book, catch other such gems of ideas I missed, and share them with others.

It all makes sense when you apply what you read to your own life.

Part 3: Customizing the Framework

The framework is, as mentioned, a barebones starting point. Over time, I’ve refined and adjusted it for my dynamic schedule. This section shares some of those improvements and insights.

Nudges

The smallest things can make a big difference when you do them over and over for a long time.

Here are a few little nudges I’ve found that make my reading experience more comfortable, and in turn, make it easier to remember what I read.

Make things easy to access

Even the smallest delays add up. If something takes an extra second each time, that second turns into hours over months of reading.

For example, think about how long it takes to grab a sticky tab from your desk and place it in your book. A couple of seconds at most. But these seconds add up. It’s a tiny task, but it breaks the flow. Over time, it creates mental fatigue.

The solution I came up with was to keep my sticky tabs inside the book. I usually use them as a bookmark. When I start reading, I move the tab palette to a page I haven’t reached yet, but still keep it tucked inside. That way, it’s always within reach.

Sometimes, I even tape the sticky tab palette to the back cover with a bit of Scotch tape. It’s quick, simple, and saves me from reaching across the desk every few seconds.

Diagonal reading

Sometimes, especially when I’m reading a non-fiction book, I come across sections that don’t feel that important. There’s nothing really worth remembering there.

But I still don’t want to skip them completely, because they often connect to the parts that actually matter.

The best way to handle this is to read diagonally.

It takes a bit of practice, but once you get the hang of it, diagonal reading becomes one of the best tools to help you get to the important stuff without losing track of the flow.

Book size

This doesn’t directly help you remember what you read, but the more you read, the more you’ll have to remember. So making reading easier matters, too.

Big books are hard to handle. They’re less portable, and if you take notes on your computer, they can get in the way, too.

If you have the option, always go for the smaller version of the same book. Get the smallest one that’s comfortable to read.

This applies to e-readers too. I used a Kindle Paperwhite for almost six years, but eventually switched to the small, basic Kindle because it fits right in my pocket, and that makes all the difference.

Summarizing each chapter

Some chapters just won’t be useful to you, even if they’re well written or make good points.

Summarizing those chapters will just slow you down. There’s nothing much in them worth remembering anyway.

Of course, for some books, your goal might be to understand every concept in every chapter. If that’s the case, summarizing each section makes sense.

But if your goal is to get the main idea or the central theme of the book, it’s better to wait until you’ve finished reading. Then you can spend your time reflecting and summarizing the whole book instead of breaking it down chapter by chapter.

Color coding and highlighting

There’s no need to color-code or highlight every book. It’s better to adjust it to your needs.

For one thing, writing or highlighting takes a setup. You need a pen or a highlighter, and then a table to keep all that. This makes you stationary. And that can be a problem if you like to read in bed.

Then it becomes a mental block.

As a solution, I adapted a hybrid setup.

I still take notes and highlight in the morning (mostly non-fiction books), but in the evening, I just use sticky tabs that I already keep inside the book. I don’t highlight or write while reading, so I can lie down on the sofa or in bed and read freely.

I used to color-code every single book, fiction and non-fiction alike. But over time, I realized I could just use a sticky tab to mark the pages I want to revisit and later pull out the interesting parts when writing my review.

Of course, some people love color-coding every book, and that makes perfect sense. But for my goals, I prefer to spend that time in Part 3 of this framework: revisiting and reflecting on the sections that matter most. In the end, it’s just a matter of preference.

The decision about how much you want to color-code, highlight, or take notes also depends on how many books you plan to read in a year.

If you only read a few books a year, you can afford to do all of these things for each one. It might even be worth it. But if you read a lot, the value of spending all that time on color coding starts to decline, and it’s better to invest that time in the review stage instead.

These aren’t perfect solutions, of course. Just trade-offs.

It’s not that serious

If the book you’re reading doesn’t interest you, put it down. That doesn’t mean it’s badly written. It might just mean you and the book met at the wrong time. Give it some space. When the time is right, it’ll be waiting for you on the shelf.

Ryan Holiday once said in an interview:

“Even if all you get is one life-changing idea from a book, that’s still a pretty good ROI.”

If your week is already packed, it’s fine to skip note-taking or other techniques. What matters more is to keep reading, to keep the habit alive. If you spot a good point along the way, you can always come back later for a focused, deep read.

It’s not that serious.

FAQs

Why do I forget what I read so quickly?

Forgetting what we read so quickly is actually our brain’s default setting. It’s not a flaw, it’s just how we’re wired.

Forgetting doesn’t mean you have a bad memory. Neuroscientists Andrew Budson and Elizabeth Kensinger explain that memory works in stages: encoding, storing, and retrieving. Most of the time, we forget because we never really encoded the information to begin with. If you read without focus or understanding, the details just don’t stick, and that’s normal.

Their research also shows that when we focus, organize, understand, and connect what we read, when we make it meaningful instead of letting the words just pass by, we remember a lot more.

This is why having a practical framework to remember what we read is extremely important.

Is there a “magic” method that ensures I remember everything I read?

There’s good news and bad news.

The good news: a system to remember what you read does exist. The bad news: it’s unique to you. How well it works depends on your personality, your job, your daily routines, and everything else life throws at you.

That means you have to start somewhere, using what you know about systems others have used. Experiment, observe, and see what actually works for you.

This is why starting with a bare-bones system is so important. Keep it simple, light, and flexible. If you try to copy a system built for someone else, like a full-time professional writer who also reads full-time, you’ll just burn out. And once that happens, reading can easily fall out of your life altogether.

Should I take notes while reading or after finishing a chapter/book?

Both have their own benefits.

Taking notes while reading feels like chatting with a stranger in a bar.

You want to catch every little detail of their story. Taking notes after finishing the chapter is more like telling your spouse about a meeting at work. You focus on the main points and skip the small stuff.

Taking notes while reading can slow you down compared to summarizing a chapter afterward. The approach you choose depends on the book. For a detailed history, like one about World War II, taking notes as you go helps lock in the facts. For a novel or a book built around a single idea, summarizing after each chapter is usually enough to remember most of it.

In short, let your note-taking match your goal. The method should serve you, not the other way around.

How often should I review my notes to retain what I’ve learned?

Reviewing too soon wastes time. Reviewing too late, and you risk forgetting.

In practice, the sweet spot is three to seven days. The forgetting curve is real. Even if you revisit notes and highlights, you need to come back to them again and again if you want them to stick long-term.

But if you’re juggling a lot of things—work, family, other responsibilities—this repeated process can become mentally exhausting. Eventually, it might even make you give up reading entirely.

A practical way around this is to do something with what you learn.

There are two main ways to do this. First, write a review or a summary of the book and the ideas you want to remember. Hold yourself accountable. Publish it somewhere people can see it.

The second way is to apply something from the book to your life. This is the most reliable way to make what you read last.

What tools should I use to store and retrieve my notes?

You can use either physical or digital tools. It doesn’t really matter. The key is to sort and categorize your notes so you can get back to them easily later.

A good tool, whether it’s a notebook or an app, has three must-have qualities: it’s easy to store information, easy to organize it afterward, and easy to find again when you need it.

No system works perfectly for everyone. If it takes too much time or effort, you end up working for the system instead of it working for you.

How many books can I apply such a system to? Won’t it become overwhelming?

Start small, and stay small until it feels natural. At first, a simple three-step framework to remember what you read might feel a bit rigid. You move from step one to step two, then step three, carefully following each stage. Over time, those steps blend into one smooth habit, and you’ll see how flexible the system can be, fitting into your everyday life.

At the start, to avoid feeling overwhelmed, pick books you really enjoy. Stick to a barebones system. Expand or add complexity only once it feels comfortable.

Does this work for fiction or more abstract/philosophical texts?

This system works for any book (fiction or non-fiction, easy or hard).

It’s not really about the book itself, but about giving you a lens to zoom in on the content.

You can even use this framework for articles, podcasts, YouTube videos, or any other information you want to absorb.

How long does it take to build this “reading memory system”?

Reading four or five books is usually enough to get used to this framework. If it still feels hard or tiring after that, it means you need to adjust it to fit your schedule and personality.

The first few books may feel slow, but as you get into the habit, using your templates, structure, and tools, it gets easier, and the benefits will grow.