Snapshot

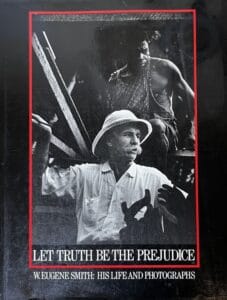

Let Truth Be the Prejudice by Ben Maddow tells the story of W. Eugene Smith, one of the most influential photojournalists in the 20th century.

The book is as unique in its writing as it is in its content. In some places, the book is written in almost poetic style, while giving a deeply personal account of Smith’s life—complete with his own letters and thoughts.

It follows Smith from his early years to his death, covering it all—the successes, the struggles, the heartbreaks, the moments of glory, and everything in between.

Table of Contents

Summary

Early Life and Influences

Eugene Smith was born in Wichita, Kansas, in 1918. From a very early age, he started taking photographs with his mother’s camera. Even then, he showed a restless drive and curiosity that never really left him.

By his mid-teens, that curiosity was starting to take shape. Sports editor Virgil Cay recalled that at just fifteen, Smith had photographs published in the Wichita Eagle. Cay described him as the kind of person who would “hang by his heels out of the press box windows” and chase every fire truck in town, all for the sake of finding a new angle.

But out of the many tragedies that would unfold in his life, the first came early. During the Great Depression, his father died by suicide—an event that haunted Smith for much of his life. Despite the loss, his mother, Nettie, pressed him to keep going with photography.

And it worked. Smith threw himself into it with even more intensity.

For him, the act of photographing was never charming—it carried a kind of tension with it. Even as a teenager, he was ambitious, self-demanding, and often torn by his own temperament. That mix of drive and inner conflict would shape not only his work, but the rest of his life.

“Cay remembered a time when Smith had been photographing a flood from an airplane, and the machine ran out of gas. Smith ordered the pilot to coast in the air with a dead motor until he finished all the shots he wanted. Cay said that Smith, in the lingo of the time, had nerve, coolness, and guts—a news editor’s ideal cameraman.”

“His letters to his mother from Notre Dame are a strange amalgam of the good child and the fractious, moody rebel. They are a diary of a bright, and at first, non-literary young man. The tone of his written voice varies between the plain hunger for sweets that would be natural in a nine-year-old away from home for the first time, and the sensitivity and boastfulness of an emerging artist.”

Artistic Philosophy and Technique

Smith’s photography techniques were unmistakably his own—dark, angry, violent, lonely, and vulnerable all at once. Yet the strange quality of photography is that it reveals as much about the person behind the camera as it does about what’s in front of it. And in Smith’s case, we don’t see a dark, violent man at all.

“Anger and sorrow fire the universe of my being. And pain is the searing twister causing freeze,” he once said of his work. His commitment was always to show the world as it was. “Let truth be the prejudice,” he declared—a philosophy that guided everything he created. His goal was to make his photographs a window to the world, to show both the good and the bad without judgment or bias.

And just like his philosophy, his techniques were distinct—restless, precise, and deeply personal.

“I overexpose flashes by about three times. Everyone says that’ll give you flat prints and blown-out highlights, but it just doesn’t work that way for me. Sure, I have to burn in the faces, but I still get all the crisp detail in the shadows.”

The result was prints dominated by deep, expressive shadows—this is the hallmark of his style. As he grew older, those shadows only deepened. You can see it throughout his work: in the soot-covered faces of Pittsburgh’s steelworkers, and in the soft, glowing light that falls on the children in The Walk to Paradise Garden.

“Study certain famous Smith images: the woman from Minamata and her maimed daughter; the mourners at the wake of the Spanish father; the three Welsh miners with their charcoal faces; the three Spanish Civil Guards in their black tricorns; the blinding stare of the black woman in the dark stockade for the insane in Haiti; and the black sweat of the Pittsburgh steelworkers. One notices that dark areas dominate the plane of the print. That’s even true of the two luminous children in “The Walk to Paradise Garden.” Smith’s technique was keyed to this ratio.”

Smith’s work also carried a strong moral weight and a clear sense of purpose.

His projects, Spanish Village and Minamata are good examples of this. His approach was never to “take photographs to show something” but to draw attention to the struggles people were living through at the time.

Career Beginnings and War Experience

In his late teen years, Smith moved to New York and began working at Newsweek, one of the major magazines at the time. But it didn’t take long for disagreements to surface. He often clashed with editors over his photographs and how they were published. Eventually, with no resolution in sight, he left Newsweek and joined another leading magazine of the era—Life.

For much of his career, Smith would work for Life, producing some of the most influential photo essays ever published. During World War II, he covered the Pacific theater, photographing the battles of Saipan, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa. On one mission, he was critically wounded by a mortar blast—a moment that left him with lasting injuries and shaped the rest of his life.

“You can’t raise a nation to kill and murder without injury to the mind… it is up to some of us who have idealism and a sense of justice and honesty to live that idealism with our whole being, even into the face of death.”

Smith’s work on World War II is recognized as excellent and carries tremendous emotional power. Behind it was his own moral drive: to take the best photograph possible, no matter the circumstances. That determination is what led him to create a powerful set of images during this time.

“The day Smith heard about Pearl Harbor, his frustration was so great that he went home to his 65th Street apartment and smashed his fist through a glass door. The next day, he was due to photograph a fashion show; “composing nothing into nothing,” he said. “I practically vomited, it seemed so damned stupid and useless.” In January, 1942, he tried to get out of this pocket of triviality by writing to the famous Dr. M.F. Agha, the art editor for the Condé Nast publications and a patron of photography. Smith was not modest, either; he had a sharp sense of his own biography:

Dear Dr. Agha:

Several years ago, there was a boy and a camera. He was a newspaper photographer—a very young newspaper photographer. Of ambition, the boy had much, an ambition to be in on the making of history.

Let others make the history—he would record it.”

The images from this period revealed a shift—Smith was no longer just a skilled photojournalist; he had become something closer to a genius.

Personal Life and Struggles

Smith’s personal life, by contrast, was always chaotic. Losing his father at a young age changed the course of his life and left a lasting mark on him.

“According to Jim Karales, the young man who worked as his darkroom assistant on the Pittsburgh project, Gene was “really pissed at my father for killing himself. If he’d only waited six more fucking months, he’d of been all right.” But of course that was 20 years and many crises later. “

Smith dealt not just with the physical pain from his war injuries and the long-term effects of medication, but also with the lasting psychological scars from his father’s suicide. These early traumas showed up in his childhood fantasies, and his letters reveal a mix of fierce rebellion and deep connection—especially with his mother.

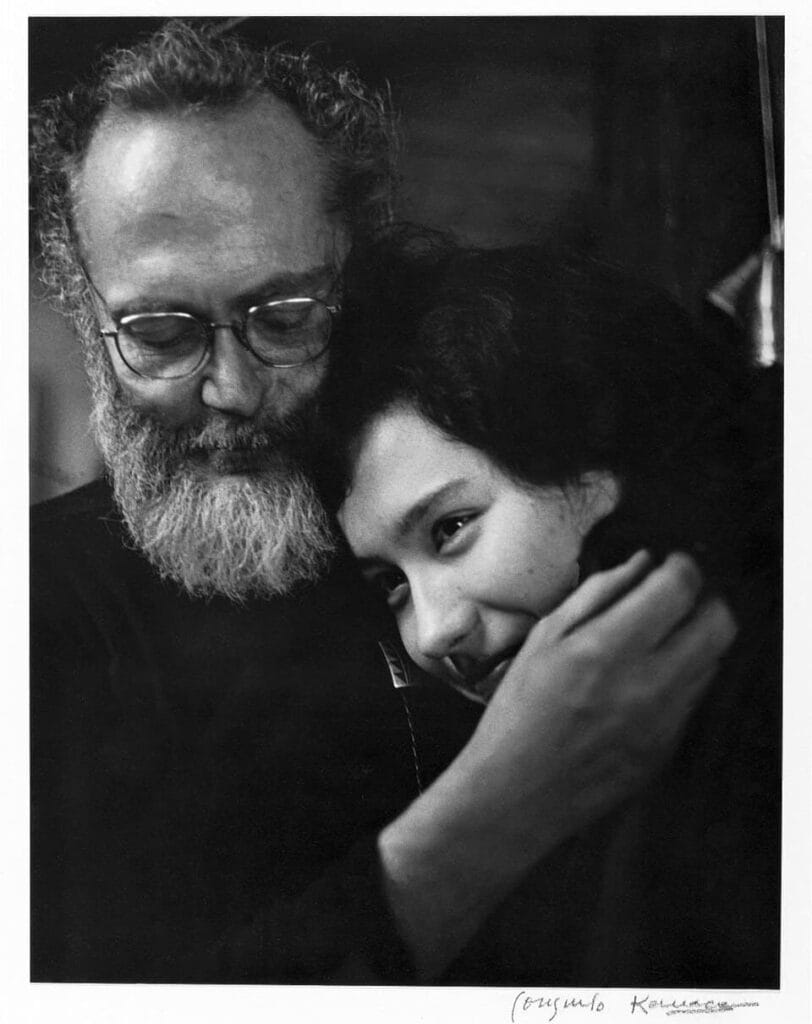

His love life was just as intense and often tragic. Carmen Martinez became his first wife, and their romance was immediate and all-consuming. Later, Aileen Sprague came into his life, first as an assistant and interpreter in Japan. But with his passion for photography, Smith couldn’t make these relationships last, eventually divorcing both of them.

On top of all this, Smith periodically faced severe mental health crises. Alcohol became his coping mechanism, but it also took a heavy toll, shortening the arc of his life. A perfectionist to the core, he devoted himself entirely to his craft, but in doing so, he compromised nearly everything else—his relationships, his well-being, and, at times, his own stability.

“Carole Thomas would confirm: “I knew both the best and worst side of Gene, not just the extremes but the nuances. There were contradictions-lovable qualities and the monstrous flaws in him that, finally, I could not tolerate. Yet, I also have memories of him as a tender, gentle and loving man-that I think is evident through as well as in his photographs. I knew the man with his child-like, electric delight in seeing and recording what he saw— yet he photographed not so much to celebrate life, but to challenge its conscience. I think that continuously looking at the dark side finally got to him, which is our loss as well as his.””

Major Projects and Photo Essays

The Pittsburgh Project (1955–1958)

Smith was commissioned by the Allegheny Conference and guided by editor Stefan Lorant to document Pittsburgh. What began as a project planned for just a few weeks stretched into nearly two years. Over that time, he produced more than 17,000 negatives, far exceeding the original scope. Yet, being a perfectionist, Smith considered the project a failure—even though today it is regarded as one of his most beloved photo essays.

The final text, though, was a compromise, and Smith was “not happy with it nor with himself.” He wrote to his friend Ansel Adams, in November of 1958: “A personal apology to you (and thus to photography) for the final failure, the debacle of Pittsburgh as printed …after four years of excruciating effort…” He had written, during this crisis, a most extraordinary letter to Nancy Newhall, the photographic historian, which could not be called lucid but which is touching because it is so brutally self-perceptive; it contains bitter puns: “And lived is the devil, backwards-and the same can be said of live evil. Dam, mad, tug, gut, eros, sore… Nema-he who does live the evil ways of Eros the Sore, having lived thus, is to be consigned to the devil. Amen.”

Minamata, Japan (1970s)

Smith met Aileen Sprague in 1970, and just a few months later, they got married. It was Aileen who first shared with him the devastating effects of mercury poisoning in a small village in Japan—Minamata. This project would go on to become one of the most influential photo essays in the history of photojournalism and ultimately, Smith’s final major work.

THE DRAMA of the poisoned fish really began in the fifties, in a small fishing town called Minamata, on a beautiful bay on the west coast of the Japanese island of Kyushu. A very large chemical firm, Chisso, had a plant nearby, which used mercury as a catalyst for acetaldehyde, which was the basis for the manufacture of that universal relic of the 20th century: plastic. The waste water from the plant was discharged directly into the sea, from which it was absorbed by the plankton. There it was changed from its original inorganic mercury into an organic poison, and so up through the food chain into the fish and, therefore, into one of the two chief sources of protein for the Japanese. The amount of mercury was enough to kill great numbers of fish and shellfish; and if they didn’t die soon enough, but were netted and eaten, the ordinary Japanese got with his meals about one tenth of the dose needed to kill him, too. This amount was considered safe by the Japanese Government, and, of course, by Chisso, too, and therefore by the town that depended upon Chisso for jobs and money.

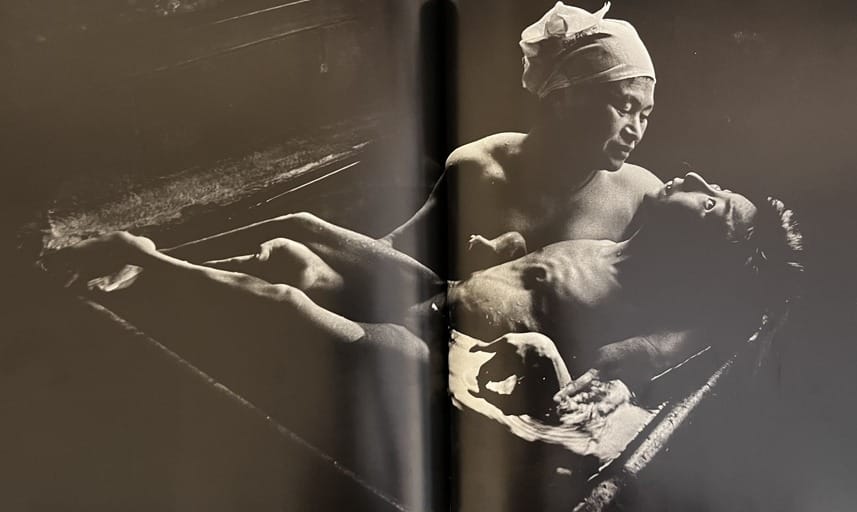

His most iconic image, Tomoko Uemura and her mother, symbolized the human cost of industrial pollution. Later, he and Aileen also co-authored a book about this project.

Other Assignments

Smith was always the friendly loner, and it gained him acceptance everywhere.

Smith had two psychological habits on such assignments, and both of them were very helpful to him. The first was to fit with gentle ease into people’s lives, never demanding or obtrusive, certainly not right away, until they grew to like and trust him. The other habit was his curious but natural tendency to idolize his subject. Dr. Ceriani was not the first, of course; Smith had been dazzled by Msgr. Sheen, by the dancer Marissa, and there would be more illustrious idols in the future. Perhaps he identified himself with these heroes and heroines; they would, in any case, give him the inner energy to continue an arduous search for a depth of understanding that had been lacking in photojournalism up to that time.

Between his Pittsburgh project and Minamata, he took on numerous assignments that would cement his reputation as one of the most important photojournalists of his time.

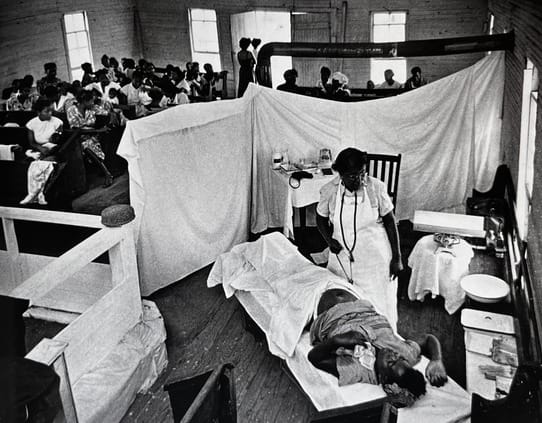

Some of his notable works include The Battle of Okinawa (1945) for Life magazine, a powerful series capturing the brutality of combat and the suffering of civilians during World War II. In Country Doctor (1948), also for Life, he followed Dr. Ernest Ceriani in rural Colorado, photographing the challenges of medical care in isolated communities. Nurse Midwife (1951) documents Maude Callen, a nurse midwife in South Carolina who provided care to poor, mostly Black communities. That same year, Spanish Village explored the everyday life in the rural Spanish village of Deleitosa under Franco’s regime. Finally, in A Man of Mercy (1954), Smith photographed a humanitarian doctor, Albert Schweitzer, at his hospital in Lambaréné, Gabon.

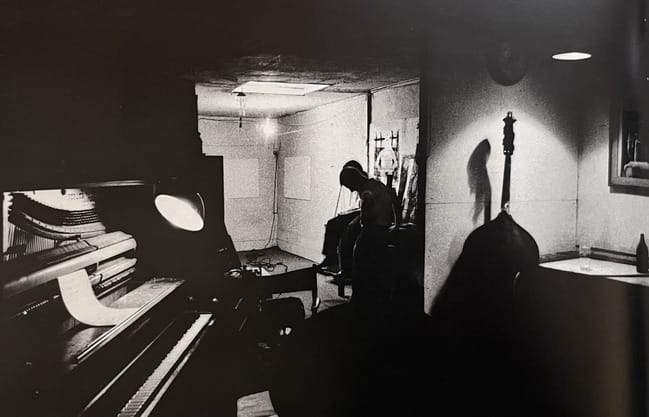

Here, there is a smiling mutual respect between Smith and the musicians. They are the people living next door, not the dry, sharp objective images of Walker Evans’ Alabamans, or the tragic, impressionistic prints of Doris Umann’s black back-country women. Smith was at home with his folk musicians, in that deeper sense of not being really at home anywhere or a genuine part of any society.

Final Years and Death

Even later in life, he stayed devoted to teaching, mentoring, and making photographs. At one point, his injuries were so bad that he couldn’t even lift a camera. But his passion for photography didn’t fade—he turned to teaching instead. He shared his knowledge at several places, including the New School for Social Research and the School of Visual Arts in New York, as well as the University of Arizona in Tucson.

After a lifetime of tremendous contributions to photography and photojournalism, Eugene Smith died on October 22, 1978. He was buried quietly at Crum Elbow Rural Cemetery in Hyde Park, New York. Yet his legacy lives on, carried through his photo essays and the generations of photographers he influenced.

The letters from Minamata alone—sent after the news of his passing—testify to the depth and reach of that legacy.

“WE COME UPON THE UNEXPECTED NEWS OF YOUR DEATH AND PROFOUNDLY CANNOT ENDURE OUR GRIEF. YOUR HISTORY IS OUR COURAGE ITSELF. WE PLEDGE OUR INHERITANCE OF THE MIGHTY FOOTSTEPS YOU LEFT BEHIND AT MINAMATA.”

Ideas that resonate with me

Eugene Smith took a tremendous amount of photographs for every project

The book mentions that when Smith was teaching students about photography, he would tell them to take at least a hundred rolls of film just to warm up their photographic muscle. He did the same for every photo essay, whether he was just starting or when he was already a legendary photographer. The beauty was always in the attempt.

Both Aileen and Gene Smith photographed; they visited the victims who were still alive and exposed about 100 rolls of film.

At one time, there were seven cameras on tripods facing outward and downward through a window; his eye was always on the alert for something happening down below. He was said to have exposed a thousand rolls through the windows into the street.

The assignment was distinguished more for its logistics than for its art. Smith and his assistant, Bernie Schoenfeld, took along nearly half a ton of equipment and supplies, including 13 cameras, and they worked, Smith boasted, “933 hours out of 1128 in six weeks, leaving us an average of about four hours sleep a night.” Heat in the phosphorous plant ran up to 600°; Smith and Schoenfeld wore asbestos coats and gloves, the latter with the tips cut off so they could operate the cameras. Both of them got blisters on their fingers, and Smith fell into a drain hole and got badly bruised. They had, at the end of the job, 5,000 negatives, out of which they selected 100 prints; 18 were printed in Life.

Eugene Smith’s photography techniques were as unique as he was

Garry Winogrand once said, “The problem to solve in photography, in general, is to show something more dramatic than what actually happened.” Eugene Smith’s pictures are a good example of this. Unlike many photographers of his time, he would take his photos with two or three exposures higher than the optimum. In other words, he overexposed his shots, letting more light through the lens than necessary.

By doing this, he was able to save the details of the shadows, the darker areas in the picture.

As a result, his photographs had rich, deep shadows that still held subtle detail. They had bright, glowing highlights, especially on faces or hands, that felt luminous without ever washing out.

The brilliant thing about this is that it creates a high emotional contrast—not just in tone, but in feeling.

The style feels hyper-real—everything ordinary, yet somehow more dramatic than it really is.

One of Eugene Smith’s most iconic photographs, Tomoko Uemura in Her Bath, is a good example of Smith’s style. By overexposing his flash on purpose and carefully burning in the highlights while printing, he captured every subtle detail — from the folds of skin to the reflective water — without losing the shadows. The result is a luminous, deeply human picture, where light almost seems to come from the subjects themselves. The balance of tone creates a sense of intense emotion, giving presence and dignity to Tomoko and her mother, and letting the viewer feel the weight of their story just by looking at a still photo.

Parts that left a mark on me

Photographs can stand alone, which, for interest, did not depend upon the public importance of the subjects. Or, for a commercial reason, if something must be emphasized, to emphasize it in the most vibrant and pictorially exciting way. That is the way I try to make pictures today.

I was nearly killed three times in three hours.” It’s unknown to which incident Smith refers. In any case: “During a bombing run I am unashamedly enjoying myself”-all this on the day before Christmas. On December 26, 1943, Smith wrote his family: “The moon was a rust blood saucer… for the cry of the night was to pierce all men, may the killing be good.” He was ill with the flu and spared them no details: “I vomited what wasn’t there.” Smith regretted: “… not being able to find Mother a decent present or the kids and felt like a heel… The tears were suddenly there and I wanted so much to give up and come home-and was ready to. But suddenly I swore to myself and reminded of work of what I must do . . . I would return. in the hazy future… with upheld head and no shame in my spine. Or if I should die it would be with courage in heart and doing a job-there is no better way to die.”

You can’t raise a nation to kill and murder without injury to the mind— and the reams of written matter calculated to bring hates to the people of the world, with all of the stupid intolerances that cause the wars in the beginning—that is the reason it is up to some of us who have idealism and a sense of justice and honesty to live that idealism with our whole being and even into the face of death. It is the reason I am covering the war, for I want my pictures to carry some message against the greed, the stupidity, and the intolerance that cause these wars and the breaking of many bodies.

How did the book change the way I think?

Photographers—even the greatest of all time—take an unbelievable number of photographs, both at the start of their careers and long after they become experts. The secret to a truly great photograph lies in the attempt itself.

Coffee chat

Who was W. Eugene Smith and what is Let Truth Be the Prejudice about?

W. Eugene Smith is one of the most influential photojournalists of the 20th century.

The book, Let Truth Be the Prejudice follows Smith from his early years to his death, covering it all—the successes, the struggles, the heartbreaks, the moments of glory, and everything in between.

Why is Let Truth Be the Prejudice considered a definitive biography of Eugene Smith?

The book includes a wealth of Smith’s own writing—personal and professional letters to friends, colleagues, and mentors—allowing the reader to grasp who he truly was. Beyond that, it traces his life from early childhood to his final days, covering all of his major works.

The second part of the book presents his most celebrated photographs. Overall, the writing and the images make the book an all-in-one, definitive guide to Eugene Smith’s life and work.

What are some of W. Eugene Smith’s most famous photo essays?

Some of his most notable works include:

The Battle of Okinawa (1945) for Life magazine, a powerful series capturing the brutality of combat and the suffering of civilians during World War II. In Country Doctor (1948), also for Life, he followed Dr. Ernest Ceriani in rural Colorado, photographing the challenges of medical care in isolated communities. Nurse Midwife (1951) documents Maude Callen, a nurse midwife in South Carolina who provided care to poor, mostly Black communities. That same year, Spanish Village explored the everyday life in the rural Spanish village of Deleitosa under Franco’s regime. Finally, in A Man of Mercy (1954), Smith photographed a humanitarian doctor, Albert Schweitzer, at his hospital in Lambaréné, Gabon.

How did W. Eugene Smith influence photojournalism?

Smith is one of the pioneers of photoessay-based photojournalism. For Life magazine alone, he completed more than 150 photo essays.

He perfected the art of visual storytelling. For his time, both his photography techniques and the philosophy behind them were uncommon. His work raised the bar for depth and narrative in photography—especially in the photojournalism genre—and has influenced countless photographers who came after him.

How did W. Eugene Smith’s personal life impact his work?

From a very young age, Smith faced a difficult life.

His father passed away when he was in his teen years, and that left a huge scar in his life.

For much of his life, he struggled with money. He could not maintain his family life and ended up divorcing twice.

On top of that, he dealt with physical injuries—some happened while covering World War II—and ongoing mental health challenges.

It seems he poured all of these troubles into his photography.

Every image was fueled, in part, by his own struggles and experiences. His photographs are deeply personal, carrying a deep emotional weight. He dedicated his life to capturing the human condition as it truly is, with empathy and honesty.