One line takeaway

A story about a lone physicist’s quest to define what freedom really is.

Snapshot

The most unsettling societies are the ones built on good intentions, not the openly tyrannical ones.

This is why, even though The Dispossessed by Ursula Le Guin is considered a utopia, you might end up thinking you read the beginning chapters of a dystopia.

In this novel, we follow Shevek, a physicist who lives on the deserted moon Anarres, much like our own moon, located in the Tau Ceti solar system. Anarres orbits the mother planet Urras. About 170 years ago, Shevek’s ancestors migrated from Urras to settle on this harsh, barren moon.

Unlike Anarres, Urras is a habitable planet with lush forests, abundant resources, and thriving cities, much like Earth.

Just like the planets themselves, the two worlds have completely different political systems. Anarres is an anarchist society with no central government. Social order is maintained by the society itself, through shared responsibilities, interdependence, and peer pressure. On the other hand, Urras is built on a capitalistic system, where there’s clear class division between rich and poor, government control, and exploitation of the working class.

Because of this political mismatch, no one in 170 years has visited their neighboring planet. Until now.

Shevek wants to break this cycle of isolation and bring peace between the worlds. The story goes on to show Shevek’s struggles to fit in both worlds and his attempt to define what freedom really is.

Table of Contents

Summary

A physicist from the moon

Roughly 12 light years from Earth lies the solar system Tau Ceti.

The story unfolds across two worlds: Urras and Anarres, both revolving around Tau Ceti. People fled from planet Urras, the mother planet, to colonize their moon, Anarres.

Urras, very similar to our Earth, is a lush, habitable world with abundant resources and thriving civilizations. Anarres, on the other hand, much like our moon, is a harsh, barren desert with limited water and scarce vegetation.

The planets aren’t the only major difference between these twin worlds; the societal structures are vastly different from one another. Urras (the mother planet) is a capitalist society, whereas Anarres (the moon) is an anarchist society where there’s no government, no private property, and no currency.

Because of this political tension, not only are the planets separated by a long distance of silence, but the people are too.

The story takes place 170 years after Anarres broke away from Urras. During this time, no one from either world has traveled to the other.

The story revolves around a young physicist named Shevek, who lives on Anarres and wants to share his work with both worlds. To do this, he travels from Anarres to Urras, becoming the first person in 170 years to make this journey.

The book alternates between his present journey on Urras and his past life on Anarres.

The political pressure between the moon and earth

Ursula K. Le Guin used this twin political system as a vessel to explore the tension between two different political views that coexist in our society: anarchism and capitalism.

On Anarres, the anarchist moon, there’s no government, no private property, and complete equality. But the social pressure creates a subtle form of oppression. There’s no such thing as rich or poor because everybody’s poor on Anarres. Everyone works all the jobs, rotating through different roles as the community needs.

On Urras, the capitalist planet, some people are wealthy and some are poor. It’s hierarchical, materialistic, pretty similar to the world we’re living in. Beautiful but deeply unequal. Freedom is gained through money, but exploitation lies beneath the surface.

The timeline

On Anarres (flashbacks):

Shevek learns about the Urras-Anarres split in his childhood and the founding of the anarchist society. In his late teen years, he meets his partner, Takver. Working as a physicist, he develops new scientific theories and slowly makes a name for himself in both worlds as an up-and-coming young scientist.

But he begins to realize that even though Anarres has no central government, the peer pressure creates a certain form of suppression. This social pressure creates its own form of control and bureaucracy.

Shevek finds himself at the tipping point of this suppression and decides to travel to Urras; to break the isolation between the worlds and bring about a resolution to the rising problems in his own world.

Those who build walls are their own prisoners. I’m going to go fulfill my proper function in the social organism. I’m going to go unbuild walls.” (Page 373)

We keep our initiative tucked away safe in our mind, like a room where we can come and say, ‘I don’t have to do anything, I make my own choices, I’m free.’ And then we leave the little room in our mind, and go where PDC posts us, and stay till we’re reposted.” (Page 369)

“You know what I want, Chifoilisk. I want my people to come out of exile. I came here because I don’t think you want that, in Thu. You are afraid of us, there. You fear we might bring back the revolution, the old one, the real one, the revolution for justice which you began and then stopped halfway. Here in A-Io they fear me less because they have forgotten the revolution. They don’t believe in it any more. They think if people can possess enough things they will be content to live in prison. But I will not believe that. I want the walls down. I want solidarity, human solidarity. I want free exchange between Urras and Anarres. (Page 159)

On Urras (present timeline):

Right after he arrives on Urras, he gets to see the difference between his own world—which is practically a wasteland—and this lush, abundant planet. He immediately comes to admire this new world.

As much as he’s impressed with Urras, the people are fascinated with him too. He’s the alien from the moon who came to visit them after 170 years.

After this initial excitement fades away, however, Shevek begins to see a part of Urras that was hidden from him. He sees the class system, the poverty, and the exploitation hidden beneath the surface. And he realizes that he’s just being used as a part of this capitalist system, to generate profit from his new theories. He’s not here to share knowledge, as he naively thought before.

Now he struggles to find freedom in either of the systems.

This realization pushes him to meet with an underground resistance against the capitalist system on Urras. These people are called the Odonians. After meeting with them, Shevek becomes part of one of their riots and lets his frustration ignite a revolution among the common people.

“You must come to it alone, and naked, as the child comes into the world, into his future, without any past, without any property, wholly dependent on other people for his life. You cannot take what you have not given, and you must give yourself. You cannot buy the Revolution. You cannot make the Revolution. You can only be the Revolution. It is in your spirit, or it is nowhere.” (Page 337)

After the riot, Shevek escapes and flees to the Terran embassy on Urras, a neutral territory.

And he finally decides not to share his theories with the Urras government but with all the worlds: Anarres, Urras, and countless others in the galaxy.

Shevek made an effort to pull himself together. He looked around the little, littered office, and at Maedda. “I have something they want,” he said. “An idea. A scientific theory. I came here from Anarres because I thought that here I could do the work and publish it. I didn’t understand that here an idea is a property of the State. I don’t work for a State. I can’t take the money and the things they give me. I want to get out. But I can’t go home. So I came here. You don’t want my science, and maybe you don’t like your government either.” (Page 330)

Ideas that resonate with me

Not a simple “capitalism bad, communism good” story

Instead of leaning towards one political camp, the story shows the pitfalls of both and shows why and how both systems can fail.

There’s no conclusion made in the book. Ursula K. Le Guin leaves it to us, with breadcrumbs leading up to our own answers. Some of the questions she leaves us with are:

What does freedom really mean?

Can any society truly be free without becoming oppressive in other ways?

Is the perfect society even possible, or will every system eventually create its own walls?

“I know it’s full of evils, full of human injustice, greed, folly, waste. But it is also full of good, of beauty, vitality, achievement. It is what a world should be! It is alive, tremendously alive—alive, despite all its evils, with hope. Is that not true?” (Page 389)

A novel’s true purpose

If you read a non-fiction book about capitalism and communism, at the very best you’d remember some facts.

You might discuss those facts with someone else, but probably not with yourself. Because more often than not, for most of us, these topics aren’t that appealing.

But it’s important to have that inner dialogue with them because the whole world runs through these systems.

This book shows how great, and superior, a novel can be to non-fiction in fulfilling that purpose. Instead of injecting ideas through a non-fiction book, wrap them around a story with a compelling yet relatable character, the author can easily ignite the reader’s burning desire to solve the problem alongside them.

Constrained and unconstrained visions

In the book A Conflict of Visions, Thomas Sowell discusses two visions that people generally see the world through.

The ones who see the world through the constrained vision believe that human nature is flawed, so social problems can only be managed through rules, tradition, and incentives.

On the other hand, the ones who base their ideas on the unconstrained vision believe that human nature is malleable, so social problems can be solved through reason, innovation, and bold reform.

In other words, the unconstrained vision is based on the idea that we can be who we want to be, whereas the constrained vision is based on the idea that we can only be who we’re capable of being.

This book is the perfect example, the fiction twin for Thomas Sowell’s non-fiction book, because both worldviews coexist in this story. Thomas Sowell introduces and discusses the worldviews, and Ursula K. Le Guin puts us in the middle where both visions coexist at their extreme ends.

The similarities between the concepts of these two books are uncanny.

The anarchist society on Anarres goes along with the unconstrained vision, where a central government is seen as unnecessary and even harmful. On Anarres, the society is designed so that there’s no central force governing it, and everything is controlled by individuals through voluntary cooperation.

On the other hand, on Urras, society is controlled completely through a capitalistic government where tradition, hierarchy, and market forces maintain order.

The two books even cite the same people who aligned with these different worldviews: Jean-Jacques Rousseau advocating the unconstrained vision and Adam Smith advocating the constrained vision.

Anarchism, which grew out of French social philosophy of the eighteenth century, posits that many of humanity’s problems come from living under governments. Jean-Jacques Rousseau had begun The Social Contract by writing “Man is born free, and is everywhere in chains.” (Page 436)

One solution to this paradoxical situation was to inaugurate representative democracies; but the anarchists found even this solution too confining, for they argued that all governments, whatever their official form, quickly become plutocracies (societies governed by the rich). Many socialists and communists argued that the path to reform lay through collective ownership of the means of production to ensure that there would be no rich. The transition to full economic democracy would be managed by a centralized, all-powerful government. Anarchists argued that such centralization could never lead to the hoped-for decentralized egalitarian society: centralization leads only to more centralization, they claimed. If people want freedom, they must claim it directly. (Page 436)

Shevek, John the savage, offred, Winston and Jonas

So far, I’ve read five dystopian and utopian novels to collect some data points—to get some fictional feedback to better understand the constrained and unconstrained visions discussed in A Conflict of Visions. They are:

The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood

Brave New World by Aldous Huxley

And now this.

The more I read such novels, the more I realized how unified and interconnected the basic premise of not just a few of them but all of them is.

All of these explore the same central theme: individual freedom.

Through Shevek in The Dispossessed, John the Savage in Brave New World, Offred in The Handmaid’s Tale, Winston in 1984, and Jonas in The Giver, the authors ask one important question: what does it mean to be truly free?

And they all intend to give the same warning through these fictional stories: people lose their individual freedom, regardless of the political structure of their respective worlds, when the needs of collective stability take over.

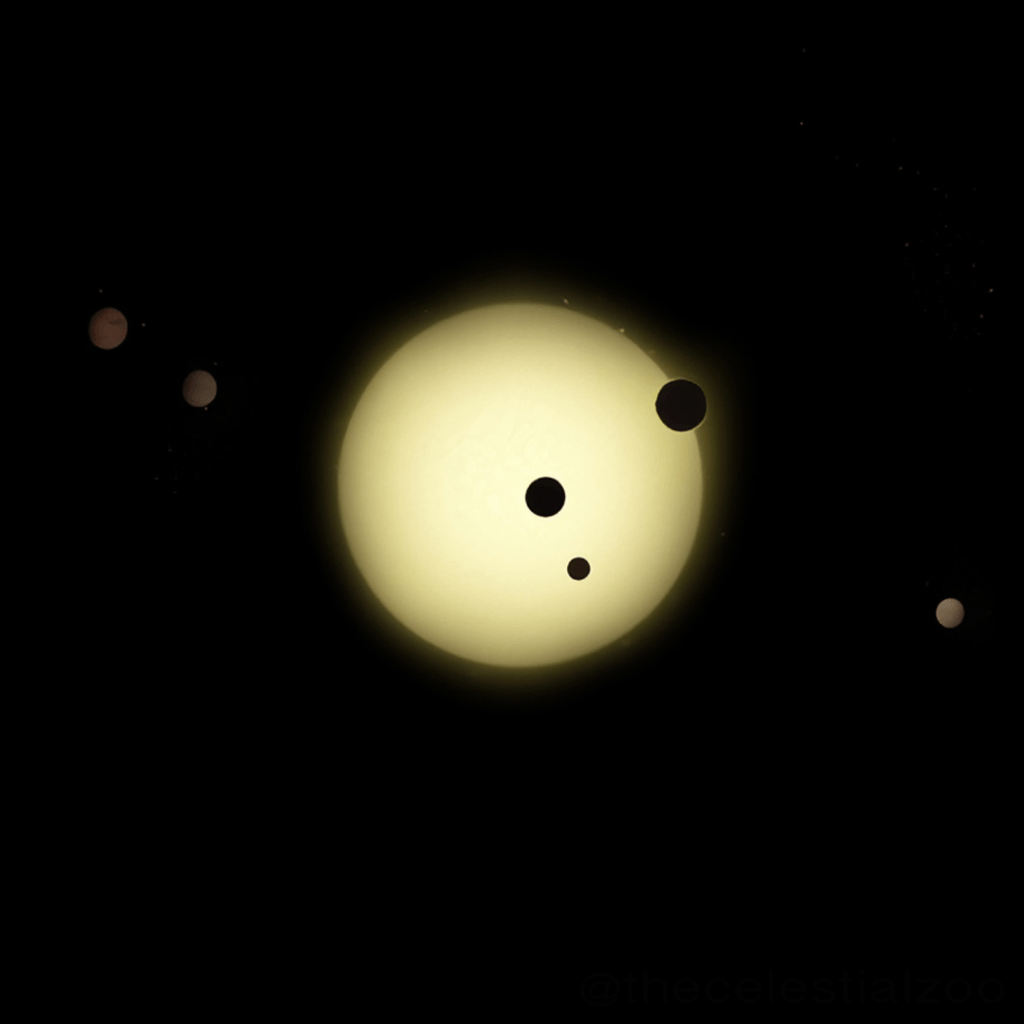

Tau Ceti planetory system

For the longest time, I overlooked the fact that Anarres and Urras are located in the Tau Ceti solar system.

The mother planet Urras is so similar to Earth and Anarres is so similar to our moon that I thought these were fictional versions of planet Earth and the moon.

It’s interesting that Andy Weir chose the same planetary system for his novel, Project Hail Mary.

“A delightful fantasy of diplomats! This castle eleven light-years from my Earth, this room in a tower in Rodarred, in A-Io, on the planet Urras of the sun Tau Ceti, is Terran soil.” (Page 382)

The cyclic process

Le Guin, in many instances, being the masterful novelist she is, weaves scientific concepts with human meaning in this book.

One of them that caught my interest is the cycle of time.

Le Guin draws on ancient cosmology and modern physics to argue that time is neither purely linear nor purely cyclic, but a tension between the two, where meaning exists only because both coexist.

“The circle?” asked the politer inquisitor, with such evident yearning to understand that Shevek quite forgot Dearri, and plunged in with enthusiasm, gesturing with hands and arms as if trying to show his listener, materially, the arrows, the cycles, the oscillations he spoke of. “Time goes in cycles, as well as in a line. A planet revolving: you see? One cycle, one orbit around the sun, is a year, isn’t it? And two orbits, two years, and so on. One can count the orbits endlessly—an observer can. Indeed such a system is how we count time. It constitutes the timeteller, the clock. But within the system, the cycle, where is time? Where is beginning or end? Infinite repetition is an atemporal process. It must be compared, referred to some other cyclic or noncyclic process, to be seen as temporal. Well, this is very queer and interesting, you see. The atoms, you know, have a cyclic motion. The stable compounds are made of constituents that have a regular, periodic motion relative to one another. In fact, it is the tiny time-reversible cycles of the atom that give matter enough permanence that evolution is possible. The little timelessnesses added together make up time. And then on the big scale, the cosmos: well, you know we think that the whole universe is a cyclic process, an oscillation of expansion and contraction, without any before or after. Only within each of the great cycles, where we live, only there is there linear time, evolution, change. So then time has two aspects. There is the arrow, the running river, without which there is no change, no progress, or direction, or creation. And there is the circle or the cycle, without which there is chaos, meaningless succession of instants, a world without clocks or seasons or promises.” (Page 252)

The prose is rich and intimate

The writing style is so vivid and tactile that it makes the reader a part of the story itself.

For example, below are two sentences about Shevek reuniting with one of his friends after a long time. As simple as it seems, she put these couple of words so brilliantly that in just two sentences, we can feel the momentum of their conversation, the joy and warmth of being reunited, almost as if her words themselves become physical.

They walked, talked, neither noticing where they went. They waved their arms and interrupted each other. (Page 184)

Does the climate and geography shape the laws and customs?

Can the political split between these planets be traced down to their ecological differences?

Urras is a planet with many natural advantages whereas Anarres is a wasteland. So does capitalism grow out of abundance and anarchism grow out of scarcity?

Although Le Guin doesn’t directly talk about this anywhere in the novel, she often distinguishes between the climate and the planetary conditions and links them to political structures. So it’s logical to assume that Anarres’ harsh climate pushes people toward cooperation and equality, whereas Urras’ lush environment allows inequality to stabilize.

Other non-fiction books that give feedback on this idea are: The Spirit of the Laws (1748), Guns, Germs, and Steel (1997), Cultural Materialism: The Struggle for a Science of Culture (1979), and The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers: Economic Change and Military Conflict from 1500 to 2000 (1989).

“Look, brother,” Shevek said at last. “It’s not our society that frustrates individual creativity. It’s the poverty of Anarres. This planet wasn’t meant to support civilization. If we let one another down, if we don’t give up our personal desires to the common good, nothing, nothing on this barren world can save us. Human solidarity is our only resource.” (Page 190)

You Urrasti have enough. Enough air, enough rain, grass, oceans, food, music, buildings, factories, machines, books, clothes, history. You are rich, you own. We are poor, we lack. You have, we do not have. Everything is beautiful here. Only not the faces. On Anarres nothing is beautiful, nothing but the faces. The other faces, the men and women. We have nothing but that, nothing but each other. Here you see the jewels, there you see the eyes. And in the eyes you see the splendor, the splendor of the human spirit. Because our men and women are free—possessing nothing, they are free. And you the possessors are possessed. You are all in jail. Each alone, solitary, with a heap of what he owns. You live in prison, die in prison. It is all I can see in your eyes—the wall, the wall!” (Page 258)

“The law of evolution is that the strongest survives!” “Yes, and the strongest, in the existence of any social species, are those who are most social. In human terms, most ethical. You see, we have neither prey nor enemy, on Anarres. We have only one another. There is no strength to be gained from hurting one another. Only weakness.” (Page 249)

Why did I pick up this book?

To get some fictional feedback on an idea I’d been thinking about for a while; one I learned from the book A Conflict of Visions by Thomas Sowell.

In his book, Thomas Sowell talks about two visions, constrained and unconstrained, that govern the human race. Turns out this book is the perfect fictional representation of those two ideas.

Parts that left a mark on me

They did not stand about sullenly waiting to be ordered to do things. Just like Anarresti, they were simply busy getting things done. It puzzled him. He had assumed that if you removed a human being’s natural incentive to work—his initiative, his spontaneous creative energy—and replaced it with external motivation and coercion, he would become a lazy and careless worker. But no careless workers kept those lovely farmlands, or made the superb cars and comfortable trains. (Page 98)

And the strangest thing about the nightmare street was that none of the millions of things for sale were made there. They were only sold there. Where were the workshops, the factories, where were the farmers, the craftsmen, the miners, the weavers, the chemists, the carvers, the dyers, the designers, the machinists, where were the hands, the people who made? Out of sight, somewhere else. Behind walls. All the people in all the shops were either buyers or sellers. They had no relation to the things but that of possession. (Page 152)

“To make a thief, make an owner; to create crime, create laws. The Social Organism.” (Page 160)

You can’t crush ideas by suppressing them. You can only crush them by ignoring them. By refusing to think, refusing to change. (Page 188)

“If you can see a thing whole,” he said, “it seems that it’s always beautiful. Planets, lives. . . . But close up, a world’s all dirt and rocks. And day to day, life’s a hard job, you get tired, you lose the pattern. You need distance, interval. The way to see how beautiful the earth is, is to see it as the moon. The way to see how beautiful life is, is from the vantage point of death.” (Page 215)

Everything is beautiful here. Only not the faces. On Anarres nothing is beautiful, nothing but the faces. (Page 258)

“There’s a point, around age twenty,” Bedap said, “when you have to choose whether to be like everybody else the rest of your life, or to make a virtue of your peculiarities.” (Page 281)

Those who build walls are their own prisoners. (Page 373)

How did the book change the way I think?

There are a lot of serious lessons I’ve taken from this book apart from the sheer pleasure of reading brilliant fiction.

But what resonates with me the most, something I think perfectly captures this book, is what Ursula K. Le Guin said during a speech: “Resistance and change often begin in art, and very often in our art, the art of words.”

Who should read it

Read this if you: enjoy slow-burn science fiction, deliberate world-building that resonates with you in the long run, are comfortable with books that ask questions instead of taking sides, think about how the world works, and like balanced endings.

Skip this if you: don’t like slow-paced world-building, don’t like “now and flashback” type fiction books, or want authors to take sides politically or ideologically.

You’ll get the most out of it if you’re: open to questioning your political beliefs, read the book slowly, pay attention not only to the character development but also to the world-building, how the environments themselves shape the political scene on two planets.

Coffee chat

What is The Dispossessed by Ursula Le Guin about?

In the novel The Dispossessed by Ursula K. Le Guin, we follow Shevek, a physicist who lives on the deserted moon Anarres—much like our own moon—located in the Tau Ceti solar system. Anarres orbits the mother planet Urras. About 170 years ago, Shevek’s ancestors fled from Urras to settle on this harsh, barren moon.

Unlike Anarres, Urras is a habitable planet with lush forests, abundant resources, and thriving cities—much like Earth.

Just like the planets themselves, the two worlds have completely different political systems. Anarres is an anarchist society with no central government. Social order is maintained by the society itself, through shared responsibilities, interdependence, and peer pressure. On the other hand, Urras is built on a capitalistic system, where there’s clear class division between rich and poor, government control, and exploitation of the working class.

Because of this political mismatch, no one in 170 years has visited their neighboring planet.

Shevek wants to break this cycle of isolation and bring peace between the worlds. The story goes on to show Shevek’s struggles to fit in both worlds and his attempt to define what freedom really is.

Is The Dispossessed worth reading?

What most people don’t like about this book is that it comes with a “science fiction” label.

Because this label is the only thing that holds it back from being recognized as one of the best novels ever written.

That said, it has its own place in literary history and has earned its status as a masterpiece of speculative fiction.

This book is very much worth reading if you’re someone who enjoys slow but brilliant world-building, likes novels that leave you with things to think about after you finish them, and appreciates books that resonate with you in the long run.

What are the main themes in The Dispossessed?

- Individual freedom and collective stability

- The tension of the political spectrum from anarchism to capitalism

- Gender equality

What is an ‘ansible’ in The Dispossessed?

An ansible is a device developed by the main character of the novel, Shevek.

It can send a message with no time delay to any place in the universe.

This device symbolizes Shevek’s ultimate goal: to connect the worlds that are separated not only by the vast distance of the universe but also by their political differences.

Can you explain the difference between Anarres and Urras in The Dispossessed and what each society represents

Anarres, where the main character comes from, is practically a wasteland—a harsh desert moon with an anarchist society based on shared resources, no property ownership, and no government.

Urras, on the other hand, is a green, wealthy planet with a capitalist system, private property, and class hierarchies.

Anarres represents the ideals of anarchism and collective stability, but it quietly struggles with social conformity and bureaucracy. Urras represents capitalism’s material abundance but struggles with inequality, exploitation, and political manipulation.

Le Guin doesn’t take sides but shows the good and the bad of both societies.

What is the significance of the subtitle “An Ambiguous Utopia” and how does it relate to the novel’s message

The most unsettling societies are the ones built on good intentions, not the openly tyrannical ones.

This is why, even though The Dispossessed by Ursula K. Le Guin is considered a utopia, you might end up thinking you read the opening chapters of a dystopia. “An Ambiguous Utopia,” therefore, fits perfectly as the book’s subtitle.

Le Guin signals that neither end of the political spectrum, anarchism or capitalism, is perfect.

Can you explain Shevek’s General Temporal Theory and the ansible device, and why they’re important to the plot

Shevek, a physicist from the world Anarres, goes to his mother planet, Urras, to share his newfound theory, the General Temporal Theory, as a peace offering to rebuild the relationship that broke 170 years ago.

The ansible is the device that emerges from this theory. It can send a message with no time delay to any place in the universe.

This device symbolizes Shevek’s ultimate goal: to connect the worlds that are separated not only by the vast distance of the universe but also by their political differences.

What makes The Dispossessed relevant today, and what can modern readers learn from it about politics and society

This book was Le Guin’s response to the Vietnam War and her studies on peace, anarchism, and nonviolent resistance.

The themes discussed in this book, individual freedom and collective stability, the tension of the political spectrum from anarchism to capitalism, and gender equality, are as relevant today as they were in the 1970s.

The story allows readers to naturally get curious and have an inner dialogue about what it takes to protect individual freedom in the face of capitalism, communism, and any mixture between these two camps.