Snapshot

The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood is a story about the power struggle between personal freedom and social stability.

In this dystopian world, women’s rights are stripped down to the bare minimum as the world is on the brink of collapse when the birth rate goes exponentially down. As a solution to maintain social stability, the remaining fertile women have been forcefully assigned to reproduction.

Summary

The world collapses into Gilead as society breaks down and a new regime rises from the chaos.

If we can’t reproduce, our society collapses, both physically and mentally.

How would we behave if the birth rate dropped suddenly across the entire world? What would the world look like?

This is the reality for the world of Gilead in The Handmaid’s Tale.

There was no one cause, says Aunt Lydia. She stands at the front of the room, in her khaki dress, a pointer in her hand. Pulled down in front of the blackboard, where once there would have been a map, is a graph, showing the birth rate per thousand, for years and years: a slippery slope, down past the zero line of replacement, and down and down. (Page 138)

Extremist leaders take advantage of the crisis. Rights are stripped away piece by piece, and people wake up in a country that’s quietly turned into a theocracy built on fear, control, and “order.”

Now, every rule, every decision is based on one thing and one thing only: how do we preserve the stability of the society?

Offred, our protagonist, finds herself in this twisted world. She’s been forced to sacrifice her body for a panic-driven solution, lending her body to reproduce because she’s part of the minority that can still have children.

The regime created an instant pool of such women by the simple tactic of declaring all second marriages and non-marital liaisons adulterous, arresting the female partners, and, on the grounds that they were morally unfit, confiscating the children they already had, who were adopted by childless couples of the upper echelons who were eager for progeny by any means. (In the middle period, this policy was extended to cover all marriages not contracted within the state church.) Men highly placed in the regime were thus able to pick and choose among women who had demonstrated their reproductive fitness by having produced one or more healthy children, a desirable characteristic in an age of plummeting Caucasian birth rates, a phenomenon observable not only in Gilead but in most northern Caucasian societies of the time. (Page 345)

The hierarchy of women in Gilead is based on what their bodies can offer.

There are certain privileges attached to each role, and to maintain this hierarchy, they come with strict rules to make sure women never unite; to divide and rule.

The roles in this hierarchy are:

Wives: the privileged but powerless

These are the women who married the higher-ranked men in society; the Commanders. Many of them are infertile, including Serena Joy, the one in the story.

Even though they get all the benefits from high society, they’ve been made powerless. They can’t work and can’t make any political decisions. So they’re completely shadowed by their husbands’ power.

But I envy the Commander’s Wife her knitting. It’s good to have small goals that can be easily attained. (Page 31)

Handmaids: the fertile women forced into reproduction

This is the role where the protagonist of the story finds herself.

Unlike Wives, Handmaids are valued because they can bear children. They’re assigned to make children for the Commanders. But the regime makes sure this is their only identity by stripping away everything else that used to be theirs.

Even their names aren’t theirs. For example, Offred, the protagonist’s name, is tied to her Commander (Of-Fred).

The fact that Handmaids create children for Commanders creates friction between the Handmaids and the Wives.

We were the people who were not in the papers. We lived in the blank white spaces at the edges of print. It gave us more freedom. We lived in the gaps between the stories. (Page 78)

Aunts: the enforcers and trainers of the system

Throughout the book, we learn about the principles and way of life in Gilead through quotes from Aunts that Offred reminds us of.

This is the Aunts’ duty. As the only women allowed to read and write, their job is to teach the new ways of this society to other women, especially Handmaids, to keep them in check. They keep Gilead functioning by convincing women to accept their roles as fate.

I also know better than to say Yes. Modesty is invisibility, said Aunt Lydia. Never forget it. To be seen – to be seen – is to be – her voice trembled – penetrated. What you must be, girls, is impenetrable. She called us girls. (Page 49)

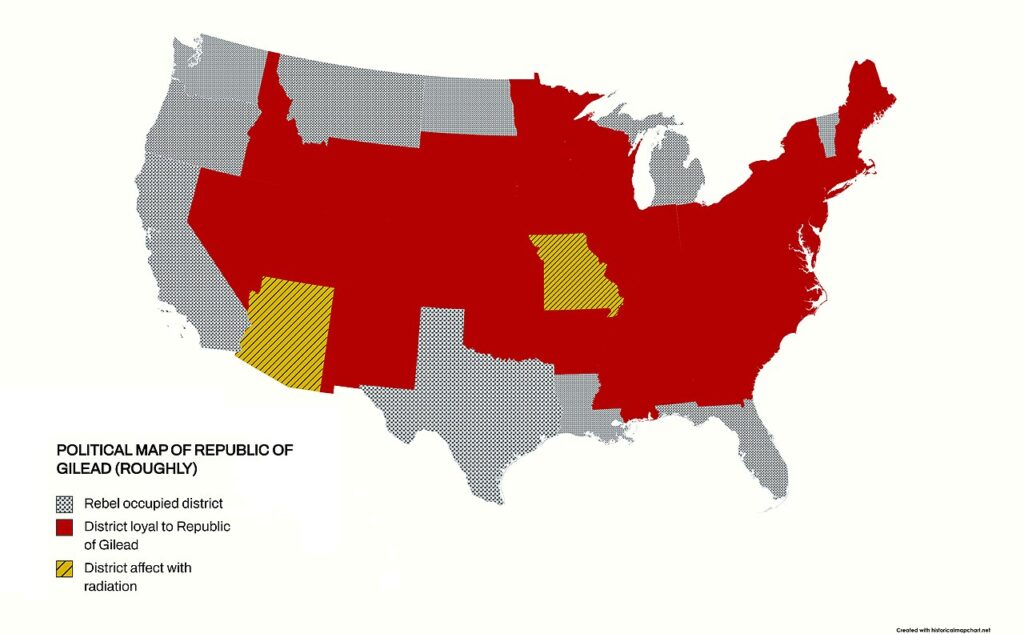

This is the heart of Gilead, where the war cannot intrude except on television. Where the edges are we aren’t sure, they vary, according to the attacks and counterattacks; but this is the centre, where nothing moves. The Republic of Gilead, said Aunt Lydia, knows no bounds. Gilead is within you. (Page 43)

Marthas: the domestic labor class

Marthas are the ones who do all the household work; cooking, cleaning, and taking care of the home.

They have more freedom to make connections with other people compared to Handmaids. But they’re only safe as long as they stay in their given role.

Econowives: the women at the very bottom of the social ladder

The difference between Wives and Econowives in this society is that, unlike Wives, who are married to the elite class, Econowives are married to the lower class.

An Econowife’s only duty is to serve her husband and bear children. She has no social status and can’t take a political stance like the Wives.

Unwomen: the outcasts sent away to die

These are the women who don’t fit into any other category, especially rebels who see through this oppressive system.

They’re sent to the Colonies to clean toxic waste, where most die quickly.

This category is Gilead’s ultimate threat: obey the rules, stay in your limits, or end up as an Unwoman.

Sometimes, though, the movie would be what Aunt Lydia called an Unwoman documentary. Imagine, said Aunt Lydia, wasting their time like that, when they should have been doing something useful. Back then, the Unwomen were always wasting time. They were encouraged to do it. The government gave them money to do that very thing. Mind you, some of their ideas were sound enough, she went on, with the smug authority in her voice of one who is in a position to judge. We would have to condone some of their ideas, even today. Only some, mind you, she said coyly, raising her index finger, waggling it at us. But they were Godless, and that can make all the difference, don’t you agree? (Page 146)

Offred becomes a Handmaid, forced to bear children for the powerful.

The story follows Offred, who was once a mother and a wife. Now she finds herself serving a Commander, her entire life shrunk down to one duty: bear children.

We see the oppression of this world through her.

Life in the Commander’s house reveals the hypocrisy at Gilead’s core.

After a few months of moving to a new house with a new Commander, Offred finds herself in a strange situation.

The Commander secretly invites Offred to “hang out” with him. He needs companionship, even though this is strictly forbidden in their society.

Offred agrees, not that she has much choice either. Through this interaction, she sees how the elite class gets protection even when breaking the law, while women are punished for even the smallest mistakes. She learns what the power dynamic of this society is really about. She sees how imbalanced it is.

My presence here is illegal. It’s forbidden for us to be alone with the Commanders. We are for breeding purposes: we aren’t concubines, geisha girls, or courtesans. (Page 166)

Offred discovers small acts of rebellion that keep hope alive.

In the same house, Nick, a Guardian who serves as the Commander’s driver and helps around the house.

Through Nick, Offred learns about “Mayday”, a resistance against the entire system. Seeing how imbalanced this system is, Offred is naturally interested and curious about this rebellion. But she keeps it under control so as not to create any problems for herself.

Gilead’s leaders break their own rules while enforcing them on others.

Two-thirds into the story, the Commander takes Offred to Jezebel’s; a secret, illegal club where powerful men gather to socialize.

The interactions during this visit bring the ideas that were growing in Offred’s mind to life. Gilead isn’t just a strict, oppressive place. It’s also deeply dishonest, hypocritical, and broken.

Even the most powerful men, with all their freedom, seek to break free from the norms, even if it breaks the rules. Because this system simply doesn’t work for anyone, even the most entitled ones.

This is a very similar idea that Aldous Huxley wanted to bring forward in his novel, Brave New World. Even if society is strictly designed to benefit a certain class, to give them everything, they still suffer because their individuality is stripped away in the process.

Seeing all this, Offred understands how much of Gilead survives through lies.

Offred’s fate becomes uncertain as the story ends in ambiguity.

At the end of the story, Nick, who’s been feeding her information about the resistance, tells her that they’re coming to rescue her and that she should trust them.

We’re kept hanging because there’s some ambiguity about whether he’s telling the truth or not. Either way, at the end of the story, she’s taken away.

Then there’s a small chapter at the end of the book called the “Historical Notes.” It takes place in 2195, about 150 years after Offred’s story, where scholars discuss the tapes; the recordings of a Handmaid.

That Handmaid is Offred.

This section gives us a hint that Offred survived after being taken away. At least she lived long enough to tell her story.

Ideas that resonate with me

The book is built on an original, yet haunting concept

The concept of the book interests me for a couple of reasons.

First, the story shows how a society can collapse under its own weight slowly, not suddenly.

The fall is logical and systematic.

Personal rights, especially women’s rights, are taken away slowly, bit by bit, until they have none. Each step of the way, the regime makes arguments to back up its actions. So, at the end, where women have absolutely no rights whatsoever, they don’t even question it because of the slow, gradual decline of their freedom.

The whole system is carefully built so that it doesn’t even enter their consciousness to question their lack of freedom.

The struggle between personal liberty and collective stability

One of the reasons I picked this book up was to get some fictional feedback on the ideas discussed in A Conflict of Visions by Thomas Sowell.

Sowell argues that there are primarily two dominant visions that govern the world; in politics, in economics, in law, and many more. These are the constrained and unconstrained visions.

The ones who see the world through the constrained vision believe that human nature is flawed, so social problems can only be managed through rules, tradition, and incentives.

On the other hand, the ones who base their ideas on the unconstrained vision believe that human nature is malleable, so social problems can be solved through reason, innovation, and bold reform.

In other words, the unconstrained vision is based on the idea that we can be who we want to be, whereas the constrained vision is based on the idea that we can only be who we’re capable of being.

Unlike some other books I’ve read to understand this, like Brave New World and 1984, The Handmaid’s Tale is interesting because both visions are in play.

The Handmaid’s Tale begins by constraining the basic rights of women, with a worldview that assumes human nature is flawed and weak. Leading with this, the regime decides to shrink women’s value to just their biological function, that is, their reproductive capacity. This is a good example of the constrained vision in play.

In the case of Gilead, there were many women willing to serve as Aunts, either because of a genuine belief in what they called “traditional values,” or for the benefits they might thereby acquire. (Page 350)

But then, as the story goes, Offred realizes how oppressive these new norms are, that this imposed conformity is pushed on them by the regime.

This is an act based on the unconstrained vision; the belief that problems can be solved by actively reshaping society and human nature itself.

In other words, this government operates on an unconstrained vision to push forward a constrained idea.

Overall, what I’ve learned by understanding this power play between constrained and unconstrained visions is that neither of them, especially when pushed to their extremes, helps human progress. Rather, they diminish it by crushing individual freedom.

This is the core premise of the book: the struggle between personal liberty and collective stability.

It’s interesting how authors like Margaret Atwood, Aldous Huxley (Brave New World), and George Orwell (1984) all touch on this same core idea. In these dystopian worlds, people lose their individual freedom, no matter their position in the social hierarchy, when the needs of collective stability take over.

Writing versus voice recordings

When I first read it, the writing style kind of irritated me.

But at the end of the book, I found out these are voice recordings. And that’s an aha moment.

I went from “what the hell’s this writing style of Offred’s” to “this is the only way the book should have been written.”

Well played, Margaret Atwood. Well played.

Parts that left a mark on me

There is more than one kind of freedom, said Aunt Lydia. Freedom to and freedom from. In the days of anarchy, it was freedom to. Now you are being given freedom from. Don’t underrate it. (Page 45)

But this is wrong, nobody dies from lack of sex. It’s lack of love we die from. (Page 128)

A man is just a woman’s strategy for making other women. (Page 148)

How did the book change the way I think?

People lose their individual freedom, no matter their position in the social hierarchy, when the needs of collective stability take over.

Coffee chat

What does the ending of The Handmaid’s Tale mean

The book ends with Offred being taken away by some men, but it’s unclear if they’re rescuing her or arresting her.

But there’s a second ending too, called the “Historical Notes,” at the very end of the book. It takes place about 150 years after Offred’s time. In this section, some scholars discuss a project, “The Handmaid’s Tale”, which is Offred’s story found on old cassette tapes. This means she at least survived long enough to record it.

How does The Handmaid’s Tale book compare to the show

The first season is very much aligned with the book, but after that, the show goes its own way.

In the book, we never learn Offred’s real name, but the show reveals it’s June right away. The book’s Offred is more passive, just trying to survive, while the show’s June is more rebellious and active.

The book is also set in an all-white society (people of color were sent to “homelands”), but the show has a diverse cast. And in the book, Offred’s story ends after one season’s worth of events. Everything that comes after in the show is new.

Why was The Handmaid’s Tale banned in schools

It’s been banned in many U.S. schools for sexual content, profanity, and being labeled “anti-Christian.”

In 2022, it was one of over 1,600 books banned across schools in 32 states. Texas cited concerns about “human sexuality” and content that might make students uncomfortable.

What does nolite te bastardes carborundorum mean in The Handmaid’s Tale

It’s mock Latin that roughly means “don’t let the bastards grind you down.”

It’s a schoolboy joke that Margaret Atwood remembered from her childhood Latin classes. In the book, Offred finds it carved in her closet by a previous Handmaid, and it becomes a rallying cry of resistance.

The phrase combines real Latin words like “nolite” (don’t) with made-up ones like “carborundorum.” It’s become a symbol of defiance in the story.

Is The Handmaid’s Tale based on real events

Yes. But they’re magnified.

This book belongs to the genre of speculative fiction, meaning it theorizes about possible futures. Margaret Atwood made a rule for herself: she wouldn’t include anything that hadn’t already happened somewhere in history.

She kept boxes of newspaper clippings documenting real events, forced reproduction in Romania under Ceaușescu, the Islamic Revolution in Iran, environmental disasters, slavery, and witch trials. Even the Handmaid system comes from the Bible (Genesis 30, with Rachel and her handmaid Bilhah).

So Gilead is a collage of events that happened in history, taken to an extreme.

Why doesn’t Offred reveal her real name in the book

By not revealing Offred’s name, Atwood emphasizes how the regime has stripped her identity.

Some readers figured out her name might be “June” based on a clue in the text, and Atwood said that’s fine because “it fits.” But not knowing her name also makes her represent all women who’ve lost their identities under oppression. This is what Atwood wanted to emphasize in the first place.

It’s also hinted in the “Historical Notes” that she might have used fake names throughout to protect people she loved.

How does Margaret Atwood use color symbolism in The Handmaid’s Tale

Colors define each woman’s role in Gilead.

Handmaids wear red. It represents blood, fertility, menstruation, and childbirth, but also shame and sin. Wives wear blue, representing the Virgin Mary and their supposed purity. Marthas (servants) wear green.

Econowives (lower-class wives) wear striped dresses mixing all these colors because they have to do all the jobs. Unwomen in the Colonies wear grey, showing they have no value to society.

Atwood got the red color from several sources: German POWs in Canada wore red (to show up in snow), and Mary Magdalene in old paintings wore red.

What is the significance of the Historical Notes section

The “Historical Notes” are set in 2195 at an academic conference, hundreds of years after Gilead fell.

In this final chapter, a male professor discusses Offred’s story as a historical artifact found on cassette tapes. But for this future society, the events that happened are merely worthy of jokes; just to amuse the audience.

It shows that even in the future, sexism exists. But it also confirms that Gilead did fall, and that Offred’s testimony survived.

Why does Gilead use biblical references to justify oppression

Gilead cherry-picks verses from the Bible to make their oppression look holy.

They base the Handmaid system on Genesis 30, where Rachel uses her handmaid Bilhah as a surrogate. They keep the Bible locked up so only leaders can read it. This way, they can interpret it however they want without anyone questioning them.

They use biblical language for everything: “Under His Eye” (for surveillance), “Blessed be the fruit” (for greetings), even punishment based on Matthew 5:29 (“if your eye causes you to sin, pluck it out”).

But Atwood makes the point that the people running Gilead aren’t really interested in religion. They’re interested in power. Religion is just their cover.

How does The Handmaid’s Tale reflect modern political issues

The book has become more relevant over time, especially after Roe v. Wade was overturned.

It warns about reproductive rights being taken away, religious extremism in government, environmental crisis, and how democracies can collapse. Atwood was primarily inspired by 1980s conservative movements, but the story is very much relevant today as well.

The Handmaid costume has become a symbol at protests worldwide.

Atwood says the book is about recognizing totalitarianism’s warning signs: controlling media, making judges do what leaders want, and taking away civil liberties.