Snapshot

The Paradox of Choice by Barry Schwartz argues that we now live in a world where choosing has become a constant activity rather than an occasional necessity. Our strategies for decision-making control not just what we choose, but how satisfied we’ll be with the choices we make.

Beyond a certain point, however, having more options makes us less happy, less satisfied, and more anxious.

The solution isn’t eliminating choice completely. It’s choosing when and where to choose.

In other words, our well-being doesn’t come from having fewer options to choose from, but from having the wisdom to know when to choose and when not to choose.

Table of Contents

Summary

Part 1: When We Choose

Finding something on a supermarket shelf is easy. Choosing which brand to buy is the hard part.

There are thousands of brands to choose from. And it’s not just supermarkets; shopping for anything has reached a point where we’re almost always exhausted. We shop for knowledge through college curricula, for entertainment, for technology, for utilities, healthcare, retirement plans, and beauty products. We choose how to work, how to love, how to pray, and even who to be.

How did it come to this? Why do we have so many options to buy the same thing, yet feel worse off for it?

One reason is the baseline assumption that more options mean more freedom, and more freedom means better outcomes.

Research suggests otherwise.

When faced with too many choices, we often don’t choose at all. One reason discussed in the book: the effort required to choose a product isn’t worth the outcome we get from it.

A large array of options may discourage consumers because it forces an increase in the effort that goes into making a decision. So consumers decide not to decide, and don’t buy the product. Or if they do, the effort that the decision requires detracts from the enjoyment derived from the results. Also, a large array of options may diminish the attractiveness of what people actually choose, the reason being that thinking about the attractions of some of the unchosen options detracts from the pleasure derived from the chosen one. (Page 20)

But this raises a question: why can’t people just ignore the endless options? Why can’t we buy something that meets the eye and call it a day?

We can’t, because we’re social animals first.

We want what others have. So there always are—and always will be—alternatives for us to choose from.

First, an industry of marketers and advertisers makes products difficult or impossible to ignore. They are in our faces all the time. Second, we have a tendency to look around at what others are doing and use them as a standard of comparison. (Page 21)

Novelist and existentialist philosopher albert camus posed the question, “Should I kill myself, or have a cup of coffee?” His point was that everything in life is choice. Every second of every day, we are choosing, and there are always alternatives. (Page 42)

Key takeaway: We now live in a world where choosing has become an inescapable, constant activity rather than an occasional necessity.

Part 2: How We Choose

The second part of the book focuses on what basis we use to choose. What mental strategies or reasoning guide our decisions?

Schwartz argues that any good decision involves six steps:

- Figure out your goal or goals.

- Evaluate the importance of each goal.

- Array the options.

- Evaluate how likely each of the options is to meet your goals.

- Pick the winning option.

- Later, use the consequences of your choice to modify your goals, the importance you assign them, and the way you evaluate future possibilities.

Figuring out our goals can be overwhelming.

Take eating at a restaurant. We either like the experience or we don’t. The way the meal makes us feel in the moment is called experienced utility.

But if we haven’t been there before, we have to choose it. We make that choice based on how we expect the experience to make us feel. This is expected utility.

Then, once we’ve been to the restaurant and had the experience, our future choices will be based on what we remember about it. This is remembered utility.

To say we know what we want is to say these three utilities align, that expected utility matches experienced utility, and experienced utility is faithfully reflected in remembered utility.

But these three utilities rarely line up perfectly.

One of the biggest reasons for this misalignment is that what we remember about the pleasurable quality of any past experience is determined by two things:

- How the experience felt when they were at their peak, and

- How they felt when they ended

This is the information we most remember about our past experiences.

The problem is that even though a product or experience peaked well or ended well, it doesn’t necessarily mean it was the best choice.

This means that we don’t often know what’s really good for us.

So it seems that neither our predictions about how we will feel after an experience nor our memories of how we did feel during the experience are very accurate reflections of how we actually do feel while the experience is occurring. And yet it is memories of the past and expectations for the future that govern our choices. (Page 52)

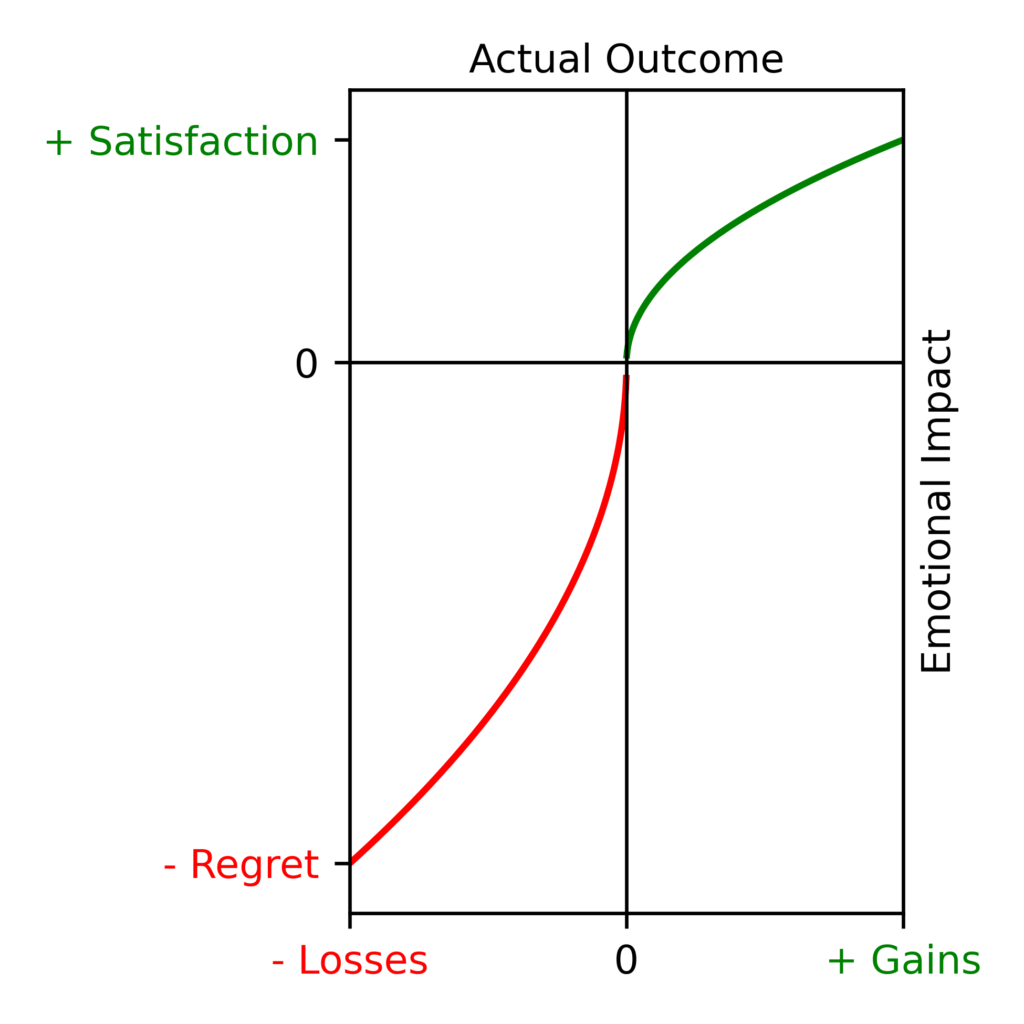

Prospect theory, introduced by Nobel Prize-winning economist Daniel Kahneman, offers an accurate model to explain this behavior.

The theory suggests that, in essence, losses loom larger than gains.

There are four interesting elements to this graph.

First, there’s an asymmetry between the curves on opposite sides of the x-axis. Losing a hundred dollars—say, to a bet—hurts much more than gaining a hundred dollars makes us happy.

It seems to be a fairly general principle that when making choices among alternatives that involve a certain amount of risk or uncertainty, we prefer a small, sure gain to a larger, uncertain one. (Page 65)

Second, the curve gets less and less steep as it moves to either side. This means that as we get richer and richer, the excitement we get from gaining more things reduces.

Third, because of this reduced sensitivity, gaining an extra $100 feels less satisfying when we already have $100 than when we have nothing. As a result, people tend to avoid risks that might increase their gains further once they’re already ahead. Gaining $200 doesn’t feel twice as good as gaining $100; it feels less than twice as good. This is why people often prefer a sure gain over a risky opportunity for a larger one, even when the expected value is higher.

Fourth, and most important, is the positioning of the neutral point.

This is the dividing line, the objective state, the actual value of a product. More often than not, our subjective mind takes charge here.

Take gas prices. Say the cash price is $3.90 and the credit price is $4.00. If we see this as a discount for cash, then $4.00 becomes our neutral point, and paying $3.90 feels like a gain. But if we see it as a surcharge for credit, then $3.90 becomes our neutral point, and paying $4.00 feels like a loss.

The difference is objective; it doesn’t change. But our baseline is subjective.

- Cash-as-discount framing

- “Gas costs $4.00. If I pay cash, I save 10 cents.”

- Reference point = $4.00

- Cash feels like a gain.

- Credit-as-surcharge framing

- “Gas costs $3.90. If I use credit, I lose 10 cents.”

- Reference point = $3.90

- Credit feels like a loss.

People seem to think that yogurt that is 95 percent fat-free is a more healthful product than yogurt that has 5 percent fat, not realizing, apparently, that yogurt with 5 percent fat is 95 percent fat-free. (Page 71)

Aversion to losses also leads people to be sensitive about giving up things they already own.

Say you bought a watch, an expensive one, and it turns out to be too clunky. After wearing it for a couple of days, you really don’t want to put it on. But the more expensive the watch, the more often you’ll try to wear it. Even if you eventually stop wearing it, you wouldn’t get rid of it. The only way you’ll let it go is after its value has mentally depreciated in your mind.

Looking at all this, the growth of options and opportunities for choice has three related and unfortunate effects:

- It means that decisions require more effort.

- It makes mistakes more likely.

- It makes the psychological consequences of mistakes more severe.

So the question becomes: how do we choose wisely?

The answer begins with a clear understanding of our goals. It’s a struggle between choosing the absolute best and settling for something that’s good enough.

The people on opposite ends of this spectrum are defined in the book as maximizers and satisficers.

The maximizer, as the name suggests, wants the absolute best. They only accept the best. These are the people who would never buy anything after visiting just one store.

On the other end is the satisficer, who settles for something good enough and doesn’t worry much about the possibility that there might be something better.

Schwartz argues that being on either side of the spectrum has its disadvantages.

When you examine an object, and it’s good enough to meet your standards, you look no further; thus, the countless other available choices become irrelevant. But if you’re a maximizer, every option has the potential to snare you into endless tangles of anxiety, regret, and second-guessing. (Page 85)

Maximizers do better objectively compared to satisficers, but they do worse subjectively.

Imagine being a maximizer, trying so hard to find the best sweater for your needs, only to discover later, by chance, that a satisficer found a better one without even trying.

This spectrum between maximizers and satisficers, Schwartz says, is a struggle between objective results and subjective experience.

Maximizers worry about finding the right fit. Satisficers worry about whether they’ll like what they buy.

The best decisions, therefore, are made somewhere in the middle, where we find a good enough product that satisfies us.

Key Takeaway: Our decision-making strategies determine not just what we choose, but how satisfied we’ll be with our choices.

Part 3: Why We Suffer

This part explores the question: why, with all these choices in front of us, do we end up unhappy despite the promise of freedom?

There are two main reasons.

First, as seen from prospect theory, as we get richer and richer, the amount of money coming in satisfies us less and less, even though we have the freedom to choose more.

Second, even if we choose the best product or experience to our knowledge, we don’t judge it on its own merit but compared to the alternatives. This is what’s called opportunity cost.

And there’s always a better alternative out there. If there isn’t one now, chances are there will be one at some point.

So we’re always in a constant struggle to get the best for ourselves. In other words, any choice we make, whether it involves $10 or $100,000, will always be a trade-off.

And trade-offs always leave a bitter taste.

This is why we suffer with any choice we make.

Key Takeaway: Beyond a certain point, more choice makes us less happy, less satisfied, and more anxious.

Part 4: What We Can Do

So how can we break out of this toxic loop of dissatisfaction in the face of endless choices?

How can we free ourselves from choice overload?

Schwartz suggests eleven ways to do this.

Choose when to choose

To avoid being miserable and overwhelmed by endless choices, we first have to decide what’s worth choosing in the first place.

Understanding what’s worth spending time on, and what’s not, saves us a lot of time we would otherwise spend worrying over something that wouldn’t have mattered anyway.

- Review some recent decisions that you’ve made, both small and large (a clothing purchase, a new kitchen appliance, a vacation destination, a retirement pension allocation, a medical procedure, a job or relationship change).

- Itemize the steps, time, research, and anxiety that went into making those decisions.

- Remind yourself how it felt to do that work.

- Ask yourself how much your final decision benefited from that work.

Be a chooser, not a picker

Choosers are people who are able to calculate on what makes a decision important, on whether, perhaps, none of the options should be chosen, on whether a new option should be created, and on what a particular choice says about them as individuals.

Choosers have the time to modify their goals. Pickers don’t.

- Shorten or eliminate deliberations about decisions that are unimportant to you;

- Use some of the time you’ve freed up to ask yourself what you really want in the areas of your life where decisions matter;

- And if you discover that none of the options the world presents in those areas meet your needs, start thinking about creating better options that do.

Satisfice more and maximize less

- Think about occasions in life when you settle, comfortably, for “good enough”;

- Scrutinize how you choose in those areas;

- Then apply that strategy more broadly.

Think about the opportunity costs of opportunity costs

When we decide to opt out of deciding in some area of life, we don’t have to think about opportunity costs.

- Unless you’re truly dissatisfied, stick with what you always buy.

- Don’t be tempted by “new and improved.”

- Don’t “scratch” unless there’s an “itch.”

- And don’t worry that if you do this, you’ll miss out on all the new things the world has to offer.

Make your decisions non-reversible

When we can change our minds about decisions, we are less satisfied with them. When a decision is final, we engage in a variety of psychological processes that enhance our feelings about the choice we made relative to the alternatives. If a decision is reversible, we don’t engage these processes to the same degree.

Practice and ‘Attitude of Gratitude.’

We can significantly improve our subjective experience by consciously striving to be grateful more often for what is good about a choice or an experience, and to be disappointed less by what is bad about it.

- Keep a notepad at your bedside.

- Every morning, when you wake up, or every night, when you go to bed, use the notepad to list five things that happened the day before that you’re grateful for. These objects of gratitude occasionally will be big (a job promotion, a great first date), but most of the time, they will be small (sunlight streaming in through the bedroom window, a kind word from a friend, a piece of swordfish cooked just the way you like it, an informative article in a magazine).

- You will probably feel a little silly and even self-conscious when you start doing this. But if you keep it up, you will find that it gets easier and easier, more and more natural. You also may find yourself discovering many things to be grateful for on even the most ordinary of days. Finally, you may find yourself feeling better and better about your life as it is, and less and less driven to find the “new and improved” products and activities that will enhance it.

Regret less

- Adopting the standards of a satisficer rather than a maximizer.

- Reducing the number of options we consider before making a decision.

- Practicing gratitude for what is good in a decision rather than focusing on our disappointments with what is

Anticipate adaptation

Our challenge is to remember that the high-quality sound system, the luxury car, and the ten-thousand-square-foot house won’t keep providing the pleasure they give when we first experience them. Learning to be satisfied as pleasures turn into mere comforts will ease disappointment with adaptation when it occurs. We can also reduce disappointment from adaptation by following the satisficer’s strategy of spending less time and energy researching and agonizing over decisions.

- As you buy your new car, acknowledge that the thrill won’t be quite the same two months after you own it.

- Spend less time looking for the perfect thing (maximizing), so that you won’t have huge search costs to be “amortized” against the satisfaction you derive from what you actually choose.

- Remind yourself of how good things actually are instead of focusing on how they’re less good than they were at first.

Control expectations

Our evaluation of experience is substantially influenced by how it compares with our expectations. So what may be the easiest route to increasing satisfaction with the results of decisions is to remove excessively high expectations about them.

- Reduce the number of options you consider.

- Be a satisficer rather than a maximizer.

- Allow for serendipity.

Curtail social comparison

- Remember that “He who dies with the most toys wins” is a bumper sticker, not wisdom.

- Focus on what makes you happy, and what gives meaning to your life.

Learn to love constraints

As options continue to multiply at an increasing rate, what we can really do for ourselves is constrain ourselves from engaging with every choice presented to us.

This is the most effective way to control the number of choices available in a free market: the customer says no to the overabundance of choice. The market has to listen and reduce the number of options.

So we bring the balance back to where it feels comfortable.

Although it sounds straightforward in theory, it takes many deliberate turns and missteps in practice. But constraining ourselves is clearly a good start.

Key Takeaway: The solution isn’t eliminating choice, but choosing when and where to choose—designing a life with intentional constraints.

Ideas that resonate with me

Objective results vs subjective experiences

When we go to Amazon or similar sites, we look at the product specifications and then go straight down to the comment section to see what other people who bought the product think about it.

We want to know how other people experienced it, how they felt using it, even more than what the objective quality of the product is.

Subjective experiences matter more than objective results.

This is why credible testimonials, whether for a personal profile or a product, convert better than expertise or objective quality alone.

Conviction that they have found a good fit makes students more confident, more open to experience, and more attentive to opportunities. So while objective experience clearly matters, subjective experience has a great deal to do with the quality of that objective experience. (Page 89)

The paradox of choice marks the boundary between the socialist economy and the capitalist economy

The paradox of choice represents a power struggle between two different economic systems.

On one end, there’s the pure socialist economy, which historically offered a limited number of options. The economic scene in the Soviet Union is a good example of this.

On the other end, there’s the pure capitalist economy, where the free market offers a plethora of options for the same product.

The core argument of this book is that we need to define a sweet spot between these two, so that we have enough variations to choose with satisfaction, but not so many that we get overwhelmed by them.

So even if, on the surface, these choices seem only related to psychological well-being, they are inherently connected to economics and therefore politics.

Choice overload makes people unhappy, but should companies voluntarily reduce options? Should governments regulate choices? Or should individuals just cope better? Each answer reflects different values about freedom, responsibility, and power.

So each choice we make, or decide not to make, moves, however slightly, the boundary between a socialist economy and a capitalist economy.

The psychology behind money-back guarantees

We are naturally attracted to the things we own.

For example, you might refuse to sell your old phone for a price you’d never pay to buy the same phone from someone else. Ownership changes how we feel about an object. Once something is ours, we don’t want to let it go.

This is a cognitive bias known as the endowment effect.

Because this is so common among all of us, people frequently put this principle into practice when they’re trying to sell something. The seller makes it easier for us to buy a product by giving us the option to return it. A good example: the money-back guarantee.

We’re naturally more open to buying something if we have the option to return it. But once we buy it, once we get to own it, we most probably won’t return it. Giving it up feels like a loss, even if we don’t necessarily like it.

As prospect theory shows, losses feel stronger than gains.

So we inflate the value of what we already have.

This phenomenon is called the endowment effect. Once something is given to you, it’s yours. Once it becomes part of your endowment, even after a very few minutes, giving it up will entail a loss. And, as prospect theory tells us, because losses are more bad than gains are good, the mug or pen with which you have been “endowed” is worth more to you than it is to a potential trading partner. And “losing” (giving up) the pen will hurt worse than “gaining” (trading for) the mug will give pleasure. Thus, you won’t make the trade. (Page 71)

Self-limitation at the individual level creates a de facto limitation at the market level

Schwartz suggests that limiting choice can reduce anxiety and regret, so we should aim to limit our choices for our well-being.

This raises the question: who decides which choices are limited?

On the surface, it seems like either customers must self-limit or governments must restrict options in more controlled economies.

But there’s a more natural solution that comes into play, especially in free markets.

When individuals adopt Schwartz’s advice and stop treating every decision as equally important, satisficing instead of maximizing, ignoring most options, sticking with defaults, the market has to respond to the customer. In a free market, there’s no other way for sellers to be profitable than to respond to the customer.

Unprofitable options get discontinued, so the number of choices naturally goes down.

So self-limitation at the individual level creates limitation at the market level, without anyone imposing it from above, from the government level. This works flawlessly because this is the core framework on which the free market is built.

In this way, the paradox resolves itself: we don’t need authorities to curate our choices. We just need to stop choosing where it doesn’t matter, and let the market do the rest.

What I didn’t like about the book

Even though there are interesting economic concepts and great insights in the book, the book as a whole doesn’t converge to a coherent idea.

The book felt like a series of good ideas rather than a coherent set of advice.

Part 2 and Part 3 in particular are insight-heavy and do a great job combining economics with psychology. But Part 4 stands alone.

All that momentum gained from Parts 2 and 3 hits a flat wall at the end.

Parts that left a mark on me

Many years ago, the distinguished political philosopher Isaiah Berlin made an important distinction between “negative liberty” and “positive liberty.” Negative liberty is “freedom from”—freedom from constraint, freedom from being told what to do by others. Positive liberty is “freedom to”—the availability of opportunities to be the author of your life and to make it meaningful and significant. Often, these two kinds of liberty will go together. If the constraints people want “freedom from” are rigid enough, they won’t be able to attain “freedom to.” But these two types of liberty need not always go together. (Page 3)

Faced with one attractive option, two-thirds of people are willing to go for it. But faced with two attractive options, only slightly more than half are willing to buy. Adding the second option creates a conflict, forcing a trade-off between price and quality. (Page 126)

Happy people have the ability to distract themselves and move on, whereas unhappy people get stuck ruminating and make themselves more and more miserable. (Page 197)

How did the book change the way I think?

Our well-being doesn’t come from having fewer options to choose from, but from having the wisdom to know when to choose and when not to choose.

Coffee chat

What is a summary of the Paradox of Choice?

We now live in a world where choosing has become an inescapable, constant activity rather than an occasional necessity. Our decision-making strategies determine not just what we choose, but how satisfied we’ll be with our choices.

Beyond a certain point, however, more choice makes us less happy, less satisfied, and more anxious.

The solution isn’t eliminating choice completely, but choosing when and where to choose, designing a life with intentional constraints.

What’s the difference between a maximizer and a satisficer in the Paradox of Choice?

The maximizer, as the name suggests, wants the absolute best. They only accept the best. These are the people who would never buy anything after visiting just one store.

This leads to more anxiety and dissatisfaction.

On the other end of the spectrum is the satisficer, who settles for something good enough and doesn’t worry much about the possibility that there might be something better.

Schwartz argues that even though satisficers are comparatively less anxious and more content with their choices than maximizers, there are drawbacks to being on either end of the spectrum. The most healthy way to deal with the paradox of choice lies somewhere between the maximizer and the satisficer.

What are the highlights of Barry Schwartz’s Paradox of Choice TED talk?

In his 2005 TED talk, Barry Schwartz challenges the Western belief that more choice equals more freedom and happiness.

He shows how too many options create more stress rather than freedom and mental well-being, using examples like retirement plan participation dropping as more fund options are offered.

He argues that too much choice can lead to decision paralysis, regret, and decreased life satisfaction.

Is the Paradox of Choice real, or has it been debunked?

The research behind The Paradox of Choice has been both challenged and validated.

One meta-analysis on choice overload in 2010, with over 5,000 participants, showed mixed results, that on average, having more choices didn’t reliably make things better or worse.

However, another study in 2015 tested four key factors: choice set complexity, decision task difficulty, preference uncertainty, and decision goal. It found that each of these factors has a reliable and significant impact on choice overload.

In other words, their conclusion is that choice overload happens not because there are too many options, but because the decision is complex, difficult, unclear, and framed as needing the “best” possible answer.

What are some examples of the Paradox of Choice in everyday life?

One famous example is the jam study, where shoppers were offered either 24 or 6 jam varieties to sample. When 24 jams were available, only 3% made a purchase. But when just 6 were offered, 30% bought a jar.

Other examples mentioned in the book include educational courses, retirement plan options, health insurance, and medical care.

And Harvard is not unusual. Princeton offers its students a choice of 350 courses from which to satisfy its general education requirements. Stanford, which has a larger student body, offers even more. Even at my small school, Swarthmore College, with only 1,350 students, we offer about 120 courses to meet our version of the general education requirement, from which students must select nine. (Page 16)

What is the main argument of The Paradox of Choice by Barry Schwartz, and how does it challenge conventional thinking about freedom

Schwartz argues that while having the freedom to choose is important for our well-being, too many choices paradoxically limit our freedom and cause anxiety and dissatisfaction.

This goes against the conventional idea that more choices mean more freedom.

The solution Schwartz suggests is to create voluntary constraints for ourselves when it comes to choosing.

He also argues that just because there’s the option to choose doesn’t mean we have to choose at all.

What are the practical strategies Barry Schwartz recommends in The Paradox of Choice to reduce decision fatigue and increase satisfaction

In the final chapter, “What We Can Do,” Schwartz provides eleven practical strategies to battle the paradox of choice and live a better life.

They are:

- Choose when to choose

- Be a chooser, not a picker

- Satisfice more and maximize less

- Think about the opportunity costs of opportunity costs

- Make your decisions non-reversible

- Practice an “attitude of gratitude”

- Regret less

- Anticipate adaptation

- Control expectations

- Curtail social comparison

- Learn to love constraints

How can I apply the principles from The Paradox of Choice to everyday decisions like shopping, career choices, and relationships

Schwartz’s core argument in this book is less is more.

The less time you spend choosing, the higher the satisfaction you’ll feel with what you’ve chosen.

But at the same time, we must be more efficient at choosing the right product or experience for us in the least amount of time possible.

The way to do this, Schwartz suggests, is by making it a point to choose only the things that must be chosen.

In other words, just because we have the option to choose something doesn’t mean we should choose it.

We are in full control of our lives when we do this, because we decide whether to choose or not to choose, no matter what external pressures exist.