Snapshot

The Righteous Mind by Jonathan Haidt shows why people split over politics and religion.

Haidt leads with two main arguments.

First, we lead with gut feelings, then use logic to defend what we already decided to believe in the first place.

Second, our minds are built to be loyal to our own group, even when it breaches moral reasoning and truth. In other words, we value reputation over truth.

So the best way to make a constructive argument with someone who has a completely different moral foundation is to speak to their intuitions first.

Once you have the permission of their intuitions, once you have this common ground, it’s much easier to make logical arguments and create a collectively useful outcome from a discussion.

Part 1: Intuitions come first, strategic reasoning second

Where does morality come from?

We all have our moral reasoning. The weird thing about them is the fact that they even change from one family member to another. Haidt questions: Where do they even come from?

The two most common answers are: (1) it’s nature (the nativist answer) or (2) it’s nurture (the empiricist answer). Haidt explores a third possibility in this section, one that has been dominating the moral psychology domain, which he calls the rationalist answer, that is, morality is self-constructed by children on the basis of their experiences with harm. The logic behind this idea is that children know harm is wrong because they do not like being harmed. On this basis, it leads them to define fairness and justice.

Haidt concludes that this hypothesis is wrong, after doing many studies testing it. His conclusions from these studies are:

First, morality is a function of culture. What seems right to someone from Western culture would be completely wrong for someone who lives in a more conservative part of the world.

Second, people’s reasoning is driven by gut feelings more so than moral reasoning.

Third, opposing the rationalist answer, Haidt argues that morality cannot be entirely driven by an individual’s understanding of harm. Using the first point, he argues that it has something to do with the culture.

We’re born to be righteous, but we have to learn what, exactly, people like us should be righteous about.

The bottom line: If morality doesn’t come primarily from reasoning, then that leaves some combination of innateness and social learning as the most likely candidates.

The intuitive dog and its rational tail

In this section, Haidt doubles down on his idea that gut feeling is the most dominant factor that shapes our moral reasoning, that it’s irrational, even though we want to believe that we are making calculated decisions, that our decisions are rational.

He introduces one of the best analogies to explain this: the rider and the elephant. The function of our mind can be divided into two parts: the irrational part, where gut feeling dominates, and the rational part, where we think that we are in control. The rational part can be explained by a rider on an elephant. The rider, our rational mind, thinks that they are in control, but they are just serving the elephant, the gut feeling, just going where the elephant wants us to go.

You can see the rider serving the elephant when people are morally dumbfounded. They have strong gut feelings about what is right and wrong, and they struggle to construct post hoc justifications for those feelings. Even when the servant (reasoning) comes back empty-handed, the master (intuition) doesn’t change his judgment.

The bottom line: intuitions come first, strategic reasoning second.

Elephants rule

Now, going with this idea that intuitions come first and reasoning second, Haidt introduces six areas of experimental research to support it.

- Brains evaluate instantly and constantly.

- Social and political judgments depend heavily on quick intuitive flashes.

- Our bodily states sometimes influence our moral judgments. Bad smells and tastes can make people more judgmental.

- Psychopaths reason but don’t feel.

- Babies feel but don’t reason.

- Affective reactions are in the right place at the right time in the brain.

If you want to change people’s minds, you’ve got to talk to their elephants.

These areas of research strengthen the idea that elephants rule, that our moral reasoning is driven predominantly by intuitions.

However, Haidt also argues that our gut feelings are not tyrannical that we have an inbuilt flexibility to change our intuitions, and they are shaped by friendly conversations, emotionally compelling arts like novels, movies, and other stories.

The bottom line: when we see or hear about the things other people do, the elephant begins to lean immediately. The rider, who is always trying to anticipate the elephant’s next move, begins looking around for a way to support such a move.

Vote for me (Here’s why)

To support the already laid out principle, that intuitions come first and strategic reasoning second, Haidt then lays out five areas of research to prove the point: moral thinking is more like a politician searching for votes than a scientist looking for answers.

In other words, the argument here is that we make up our mind first and then look for evidence to prove it to ourselves.

There are 5 areas:

- We are obsessively concerned about what others think of us, although much of the concern is unconscious and invisible to us.

- Conscious reasoning functions like a press secretary who automatically justifies any position taken by the president.

- With the help of our press secretary, we are able to lie and cheat often, and then cover it up so effectively that we convince even ourselves.

- Reasoning can take us to almost any conclusion we want to reach, because we ask “Can I believe it?” when we want to believe something, but “Must I believe it?” when we don’t want to believe. The answer is almost always yes to the first question and no to the second.

- In moral and political matters, we are often groupish, rather than selfish. We deploy our reasoning skills to support our team and to demonstrate our commitment to it.

The bottom line: The worship of reason is a delusion. The reason is just a front for our gut feelings, to convince ourselves that we are in control.

Part 2: There’s more to morality than harm and fairness

In part 2, Haidt shows what those intuitions, the gut feelings are, and where they come from.

To explain this, he uses a map of moral space and shows what specific components of this map are more favorable to conservatives than to liberals.

Beyond WEIRD morality

Westerners who are educated, industrial, rich, and democratic (WEIRD), Haidt shows, are outliers on psychological measures.

The main argument is that the WEIRDer you are, the more likely you are to see the world as separate objects, not as a connected whole.

Haidt also makes the argument that the moral domain varies across cultures. What seems okay for an Easterner would be completely wrong for a Westerner.

For example, WEIRD cultures put a lot more emphasis on the ethic of autonomy, that is, moral concerns about individual harm, oppressing, or cheating other individuals.

The bottom line: A moral matrix doesn’t just shape how we see the world, it locks us into a tribe. It pulls people together while quietly narrowing their field of vision, making it hard to notice that other moral frameworks even exist, let alone make sense. And once you’re inside one of these systems, it becomes genuinely difficult to imagine that multiple versions of moral truth, or multiple legitimate ways of judging a society, could all be real at the same time.

Taste buds of the righteous mind

Morality is like taste in many ways, an analogy made long ago by Hume and Mencius.

In other words, we make moral reasoning based on not one single idea but a series of ideas.

The bottom line: Five good candidates for being taste receptors of the righteous mind are care, fairness, loyalty, authority, and sanctity.

The moral foundation of politics

In this section, Haidt goes through each and every one of the five foundations that he introduced in the previous section, explaining why each evolved to become a moral foundation in the first place and then how it shapes our decisions in real life.

- Care / Harm: Rooted in the need to protect vulnerable children, this foundation sharpens our sensitivity to suffering. It pushes us toward empathy and makes cruelty feel intolerable.

- Fairness / Cheating: Born from the challenge of cooperating without being exploited, it tunes us to who can be trusted. It rewards honest partners and drives the impulse to punish those who take advantage.

- Loyalty / Betrayal: Shaped by the need to build and maintain coalitions, it orients us toward team players. It strengthens trust within the group and makes betrayal feel like a deep moral offense.

- Authority / Subversion: Emerging from life within hierarchies, this foundation helps us read status, rank, and role-appropriate behavior. It steadies social order by signaling when someone steps out of line.

- Sanctity / Degradation: Originally tied to avoiding pathogens and the dangers of the environment, it later expanded into a moral instinct. It lets us treat certain objects, rituals, or symbols as sacred, or deeply contaminating, in ways that hold groups together.

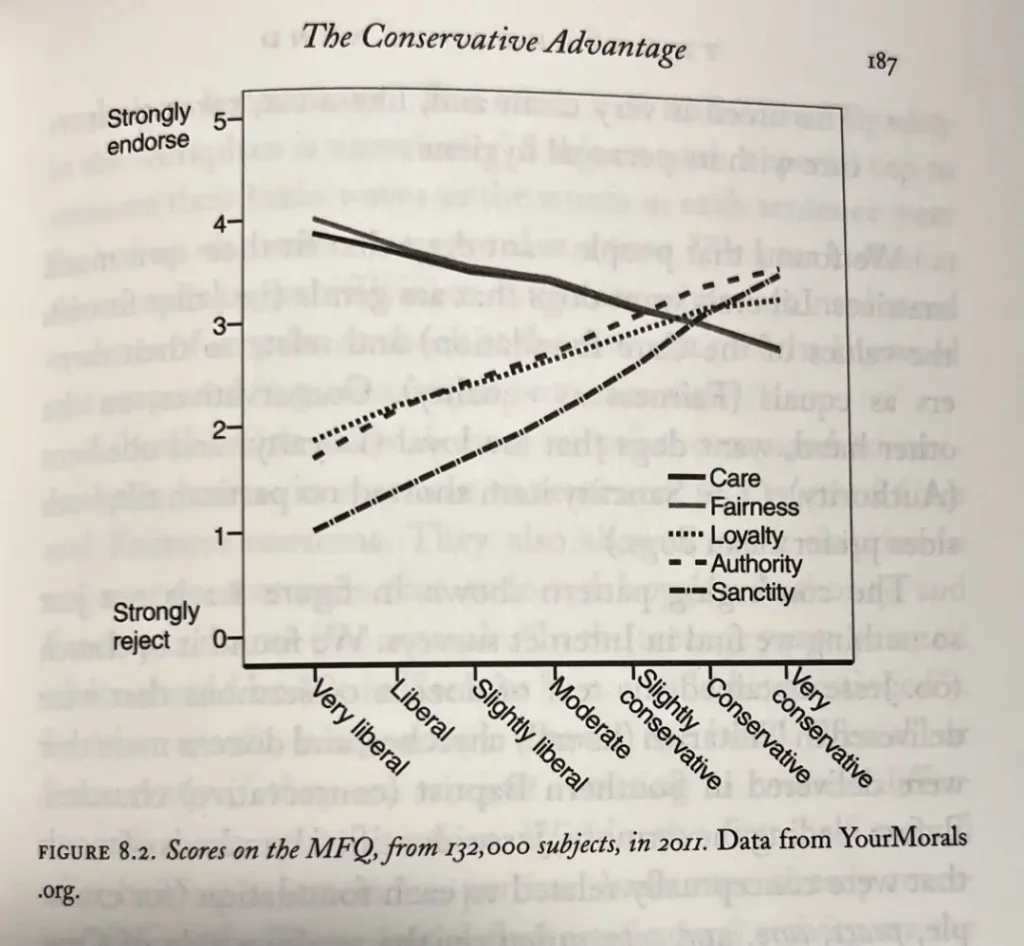

Based on these five foundations, Haidt makes one of the most important arguments in this book, that is, the current political spectrum is divided based on these five pillars of moral reasoning.

With evidence, he shows that the left relies primarily on the care and fairness foundations, whereas the right uses all five equally when forming arguments.

The bottom line: The left relies primarily on the Care and Fairness foundations, whereas the right uses all five.

The conservative advantage

Now armed with the insights from the previous section, Haidt turns to explaining some of the recurring questions in the political scene.

For example, why has the Democratic Party (left-leaning) had so much difficulty connecting with voters since 1980?

Haidt argues that Republicans (right-leaning) have developed a better system of talking to people by speaking directly to the elephant, that is, to people’s intuitions, not the rational reasoning that comes second. And the Republican Party triggers all five moral foundations: care/harm, fairness/cheating, loyalty/betrayal, authority/subversion, and sanctity/degradation.

| Viewpoint | How Society Works | What It Prioritizes |

|---|---|---|

| Conservatives | Society is held together through family, order, and stable hierarchies | Tradition, cohesion, shared identity |

| Liberals | Society thrives when individuals are free to choose their own paths | Openness, autonomy, diversity |

Then, to reinforce the argument about the five moral foundations, Haidt revises the Moral Foundation theory by (1) adding liberty/oppression and (2) modifying the fairness foundation.

Liberty / Oppression:

This foundation surfaces whenever people sense someone trying to dominate or control them. It’s the instinct that makes us push back against bullies, resist unfair authority, and defend personal freedom. It explains why the political left rallies against oppression, and why libertarians, and some conservatives, have that fierce “don’t tread on me” streak.

Fairness (Proportionality):

Fairness starts with the basic idea of returning good for good and not letting others take advantage of you.

But once humans lived in communities where reputation and punishment mattered, fairness evolved into something deeper: a strong sense that people should get what they deserve. Cheaters should face consequences, and people who contribute should be rewarded proportionately to their actions.

Now altogether, there are six moral foundations, and all six of them appeal to Republicans, while only three of them appeal to Democrats.

With these updated foundations, the theory can finally make sense of a question Democrats keep struggling with: why many rural and working-class voters choose Republicans, even when Democrats are the ones pushing for more economic redistribution?

Haidt argues that people are voting according to their moral priorities. Rural and working-class Americans tend to favor the values of order, loyalty, authority, and sanctity (the six-foundation morality), rather than the left’s focus on care, fairness, and liberty (the three-foundation morality). Their votes reflect what feels right to them, not what benefits them economically. As the book puts it, intuitions come first, reasoning second.

It’s really interesting to explore why.

Why do the working class value order, loyalty, authority, and sanctity over economic advantage?

The short answer to this question is community.

See the section Ideas that resonate with me for the full explanation.

The bottom line: People are voting according to their moral priorities, not necessarily to their economic benefits.

Part 3: Morality binds and blinds

Why are we so groupish?

In this section, Haidt lays out the work done on natural selection and its emphasis on operating as an individual.

Then, he shows the flip side where research shows our tribal nature; our tendency to operate as a pack.

Combining all this knowledge, Haidt organizes all such studies into four “exhibits.”

- Exhibit A: Major transitions create superorganisms. When free-riding is controlled at one level, groups can form larger, cooperative entities with division of labor and altruism.

- Exhibit B: Shared intentionality builds moral matrices. Humans’ ability to share intentions allowed early groups to cooperate, divide labor, and develop shared norms.

- Exhibit C: Genes and cultures coevolve. Shared intentions triggered a cycle where customs, norms, and institutions shaped which groupish traits were adaptive, giving us instincts to mark and favor our own groups.

- Exhibit D: Evolution can be fast. Human evolution accelerated over the last 12,000 years. Cultural and environmental upheavals reshaped our minds, so modern hunter-gatherers don’t perfectly reflect our ancestral nature.

The bottom line: We humans have a dual nature. We are selfish primates who long to be a part of something larger and nobler than ourselves. We are 90 percent chimp and 10 percent bee.

The hive switch

- Happiness comes from between, not within. Happiness emerges from the right relationships, between yourself and others, your work, and something larger than yourself.

- We evolved to live in groups. Our minds balance competition within groups with cooperation across groups, making social connection central to well-being.

- The hive hypothesis. Humans can, under special circumstances, transcend self-interest and merge with something larger. This is what Haidt calls the “hive switch.” These moments of unity, or “transit to the sacred,” bring our greatest joy.

- Flipping the hive switch. Awe in nature, certain rituals or substances, and collective experiences like raves can activate our hive switch. Oxytocin bonds us to our group, and mirror neurons help us empathize, especially with those who share our moral matrix.

- Parochial love. Evolution favors love within groups, not universal love. Shared fate, similarity, and control of free riders(from the elephant and the rider example) amplify this group-focused connection, and that may be as close as we get to unconditional love.

Bottom line: Happiness comes from connecting with others and being part of something bigger, with our strongest bonds naturally focused on our own group.

The religion is a team sport

- Religion is about belonging, not just beliefs. If you only focus on gods or supernatural ideas, you’re missing the bigger picture. For tens of thousands of years, religions have held people together in groups, often by making certain people, books, or principles sacred and unquestionable.

- Gods enforce cooperation. Early humans who used beliefs to build moral communities boosted trust, cut down on cheating, and kept their groups strong. Only groups that could inspire real commitment thrived.

- Religion and society evolved together. Over time, moral instincts and religious practices shaped each other. When agriculture arrived, this process sped up, favoring groups whose gods encouraged cooperation and whose members actually followed the rules.

- Caring beyond yourself. Religion taps into our ability to care about something bigger than ourselves. It helps people form teams to pursue shared goals. Politics works similarly: team loyalty drives behavior, but it can also blind us to the good intentions and morals of those on the other side.

Bottom line: Religion binds people into cooperative groups, strengthening trust and shared purpose, and channels our capacity to care for something larger than ourselves; just as politics does.

Can’t we all disagree more constructively?

- Ideologies reflect predispositions. People aren’t randomly liberal or conservative. Brains tuned to novelty and low threat sensitivity tend toward liberalism; brains tuned the opposite way resonate with conservative narratives.

- Teams shape perception. Once people join a political team, its moral matrix filters everything they see. Arguments from outside the matrix rarely change minds. This is the nature of our group-ish behaviour.

- Liberals struggle with binding foundations. Loyalty, authority, and sanctity often seem irrelevant to them, making it hard to recognize core moral resources that sustain a community.

- Yin and yang of politics. On the other hand, liberals excel at care, spotting victims, and pushing reform. Libertarians sacralize liberty, and social conservatives sacralize traditions and institutions. Together, they balance reform with stability, ensuring societies don’t destroy what sustains them.

I suggested that liberals and conservatives are like yin and yang, both are “necessary elements of a healthy state of political life,” as John Stuart Mill put it.

- Civil politics require structural change. Polarization isn’t solved by niceness. It requires changes to elections, institutions, and political environments. Morality binds us to teams, and blinds us to the good and insight in the opposing side.

Bottom line: People’s political leanings reflect their instincts, and team loyalty shapes how they see the world. Healthy politics needs a balance of care and stability, but real change comes from better institutions, not just arguing or being nice.

Part 4: Conclusion

This book shows why people split over politics and religion. It’s not because one side is “good” and the other is “evil.” It’s because our minds are built to be loyal to our own group. We lead with gut feelings, and then use logic to defend what we already believe. So when someone comes from a different moral world, with different values and priorities, it’s hard for us to really understand them because we’re hard-wired to stick with our own team.

But most importantly, it’s not impossible, just hard.

Ideas that resonate with me

Why do the rural and working class vote differently?

One of the questions that came to mind reading part 2 is why rural and working class voters vote differently.

Why do they favor order, loyalty, authority, and sanctity over their own economic gains? This seems completely illogical.

Research shows that this is because such values help bind communities together and make our social lives more predictable, therefore more comfortable. As mentioned in the book, we are so groupish that we are comfortable even overlooking our economic gains to preserve social stability; being safe and respected.

It’s easy to get triggered by some of the concepts of this book

The way Haidt’s research turned out has a clear asymmetry when it comes to the moral foundations of politics.

For example, one of the most striking arguments in this book is that liberals are predominantly sensitive to only three moral foundations, whereas conservatives are sensitive to all six in equal amounts.

Now, on the surface, this makes it seem like liberals are missing something. When I look at the reviews for this book and then the comments under those reviews, more often than not, I see someone who complains about this.

But Haidt’s point is not that liberals are missing something from a complete picture and conservatives get it, rather, liberals choose to define morality by three of the foundations that Haidt mentions in the book. They are not actually missing anything, but they actively refuse to believe three of those concepts should be involved in shaping moral foundations in the first place.

There’s a subtle difference.

Haidt’s writing style was not my cup of tea

I liked this book, learned a lot from it, and I see that these concepts are going to resonate with me in the future.

But I couldn’t like Haidt’s writing style. Not the writing, of course, but the style of writing, although I understand why he wrote this book the way he wrote it. The writing is too personalized and opinionated for my liking. There are so many places where we actively have to analyze the context to figure out the main point, even in the short summaries at the end of the book chapters.

I can’t say for sure that human nature was shaped by group selection, there are scientists whose views I respect on both sides of the debate.

Moral psychology is, of course, not math; it’s always evolving, and the problems aren’t mathematical but philosophical.

So uncertainty is a certainty for this kind of field. Haidt’s style tries to match the complexity of such a subject with transparency and honesty, at the cost of clarity.

But I would have appreciated it if he could stay away from mere opinions as much as possible.

Do you have to compromise truth to gain trust?

Early in the book, I came across this sentence in a short summary for a chapter.

That depends on which you think was more important for our ancestors’ survival: truth or reputation.

This goes along with the idea in part 3, that we are groupish; we would do anything to stabilize ourselves in a group, even if we have to sacrifice the truth for it.

This means that our intuitions sometimes move our heads away from the truth in order to survive. In other words, our minds alter the truth so that we can align ourselves with our group.

So the ideal case is that we align all three—the truth, ourselves, and our group—toward the same direction. How can we do this?

We can achieve this by building communities that value honesty as much as loyalty. So, we need both parties, the liberals and the conservatives, to build a prosperous community.

What’s the difference between libertarians and liberals by definition?

Liberals see government as a tool for fixing problems; libertarians see government as the problem.

| Liberals | Libertarians |

|---|---|

| Support government action to reduce inequality and protect vulnerable groups. | Want minimal government, especially in markets and personal decisions. |

| Believe the state should play an active role in regulation, social programs, and welfare. | Believe individuals should be as free as possible to make their own choices without state interference. |

| Prioritize care, fairness, and social justice. | Prioritize individual liberty above most other values, even if it reduces equality or weakens safety nets. |

What is the best way to debate?

So the big question is: with all these differences between liberals and conservatives, what is the most constructive way to debate and get the best out of a discussion?

A solution for this is introduced in part 2 of the book. Intuitions come first and reasoning second. This means, if we want to change someone’s mind, we need to talk to their elephant—their core moral values, not to the rider—their logical reasoning. Because the logical reasoning is just there to support their gut feelings.

If you try to talk to the rider, they will find all the evidence in the world to prove you wrong. Even if they couldn’t find any evidence to do so, most likely the debate will not go constructively. The best way to find common ground is to get permission from the elephant.

For example, say a liberal and a conservative argue about climate regulations. If the liberal says, “The science is clear. Emissions must be reduced. Here are ten graphs showing why you’re wrong,” they are talking to the rider, not the elephant.

In the meantime, the conservative’s elephant—their gut feeling—is thinking about big government overreach, loss of jobs, and a possible threat to traditions and industry. So even before the conservative opens their mouth, they have already decided that the liberal is wrong about this. Now they are just trying to find counter evidence to prove the liberal is wrong.

However, if the liberal started the debate instead like this: “We all care deeply about keeping our communities strong and independent. That’s exactly why we need American-made clean energy, so we control our own future, protect jobs, and stay competitive.”

Now, both of them are on the same page, even though nothing has changed in this argument. Now, the conservative’s elephant is calm. It gives the green light to a constructive debate.

It’s also important to note that these are not tricks; ways to outsmart somebody. It’s about understanding, empathy, and the collective well-being of our society.

Parts that left a mark on me

We’re born to be righteous, but we have to learn what, exactly, people like us should be righteous about.

I suggested that liberals and conservatives are like yin and yang, both are “necessary elements of a healthy state of political life,” as John Stuart Mill put it.

Morality binds and blinds. It binds us into ideological teams that fight each other as though the fate of the world depended on our side winning each battle. It blinds us to the fact that each team is composed of good people who have something important to say.

How did the book change the way I think?

Understanding somebody’s point of view, their gut feeling, where they are coming from, is extremely important to a constructive debate, more so than just arming yourself with evidence to prove your theory.

Coffee chat

What are the six moral foundations in The Righteous Mind by Jonathan Haidt?

The six moral foundations are Care/harm, Fairness/cheating, Loyalty/betrayal, Authority/subversion, Sanctity/degradation, and Liberty/oppression.

How does Jonathan Haidt explain why liberals and conservatives disagree?

Haidt argues that liberals are more sensitive to three of the six moral foundations mentioned in the book, whereas conservatives are sensitive to all six of them equally.

This creates tension because some of the foundations that conservatives base their moral reasoning on do not make any sense to liberals at all, because liberals refuse to believe that such foundations are a part of moral reasoning in the first place.

What does the elephant and rider metaphor mean in The Righteous Mind?

Intuitions come first and reasoning second.

Haidt’s metaphor to explain this clearly and vividly is by imagining an elephant and its rider; the elephant being our intuitions and the rider being our logical reasoning. The elephant makes the first move, and the rider just follows along.

Why does Haidt say intuitions come first and reasoning second?

Haidt says intuitions come first and reasoning second because our gut feelings drive our judgments, and reasoning mainly serves to justify those feelings afterward, rather than lead them.

For instance, on issues like abortion, climate policies, and higher education funding, we have already made up our minds about what we think, even though we don’t realize it. When we talk about it, we are just trying to prove our stance by giving evidence that aligns with our position.

The choosing happens instantaneously, like a gut feeling. Our logical reasoning just follows along.

Is The Righteous Mind arguing that conservatives are more moral than liberals?

Absolutely not.

Haidt argues that liberals see things differently than conservatives when it comes to morality.

For instance, Haidt introduces six moral foundations in this book: Care/harm, Fairness/cheating, Loyalty/betrayal, Authority/subversion, Sanctity/degradation, and Liberty/oppression. Liberals build their morality around three of them, and conservatives around all six of them.

Why do liberals only use two or three moral foundations while conservatives use all six?

According to Haidt, liberals focus mostly on Care/harm and Fairness/cheating (sometimes Liberty/oppression), while conservatives draw on all six foundations: Care, Fairness, Loyalty, Authority, Sanctity, and Liberty.

The reason behind this is that liberals are more open to novelty, diversity, and change. The three foundations on which they base their morality support them in reinforcing this openness.

On the other hand, conservatives are more sensitive to threats, loyalty, and group cohesion. This is why they tend to revolve around all six equally.

What does Haidt mean when he says morality binds and blinds?

Haidt’s two main arguments in this book are: (1) intuition comes first and reasoning second, and (2) human beings are naturally groupish—that our minds alter moral reasoning on the basis that it supports securing our place in a group.

This is what Haidt means by morality binds and blinds, that morality is driven by intuitions, not necessarily by truth. And it binds us to a group.

How can I change someone’s mind about political issues according to The Righteous Mind?

You need to talk to people’s intuitions first, not their logical arguments.

In other words, it’s more important to understand what people’s moral values are before stepping into facts or numbers.

For more information, see the section “What is the best way to debate?”

Does The Righteous Mind prove that reason cannot lead us to moral truth?

No. Haidt doesn’t say reason cannot lead to moral truth. He argues that our intuitions usually come first, and reasoning often serves to justify those gut feelings. Reason can still guide reflection, debate, and understanding, but it rarely initiates moral judgment on its own.

Why does Haidt compare moral foundations to taste receptors on the tongue?

Haidt compares moral foundations to taste receptors because, just as different receptors detect different flavors, each moral foundation responds to a distinct type of moral concern. Together, they create a rich “moral palate”, shaping how people experience and judge right and wrong.

These moral foundations are: Care/harm, Fairness/cheating, Loyalty/betrayal, Authority/subversion, Sanctity/degradation, and Liberty/oppression.