Snapshot

Tunnel 29 by Helena Merriman tells the true story of a remarkable escape from one of the most infamous barriers ever built by humans.

Table of Contents

Book Summary

A ‘unique’ wall

There are lots of famous walls we all know, the Great Wall of China, and a few others, but Berlin was different. Both physically and philosophically, it was something else.

It marked the tipping point of years of pressure between East and West. After World War II, Germany was in a weird place. The city was broken in half. The Soviets took the East, the Allies held the West. Berlin, stuck in the middle of East Germany, got split too.

Obviously, that wasn’t ideal for the people living there. One half ran a completely different political agenda than the other. In the East, people started feeling the weight of new social rules. What happened next was predictable; people started moving from East to West, from communism to capitalism.

By the early ’60s, East Berlin had become the escape hatch. Every day, thousands slipped into West Berlin. Most of them never came back. It got so common, people even gave it a name: torschlusspanik, “the rush to get out before the door slams shut.”

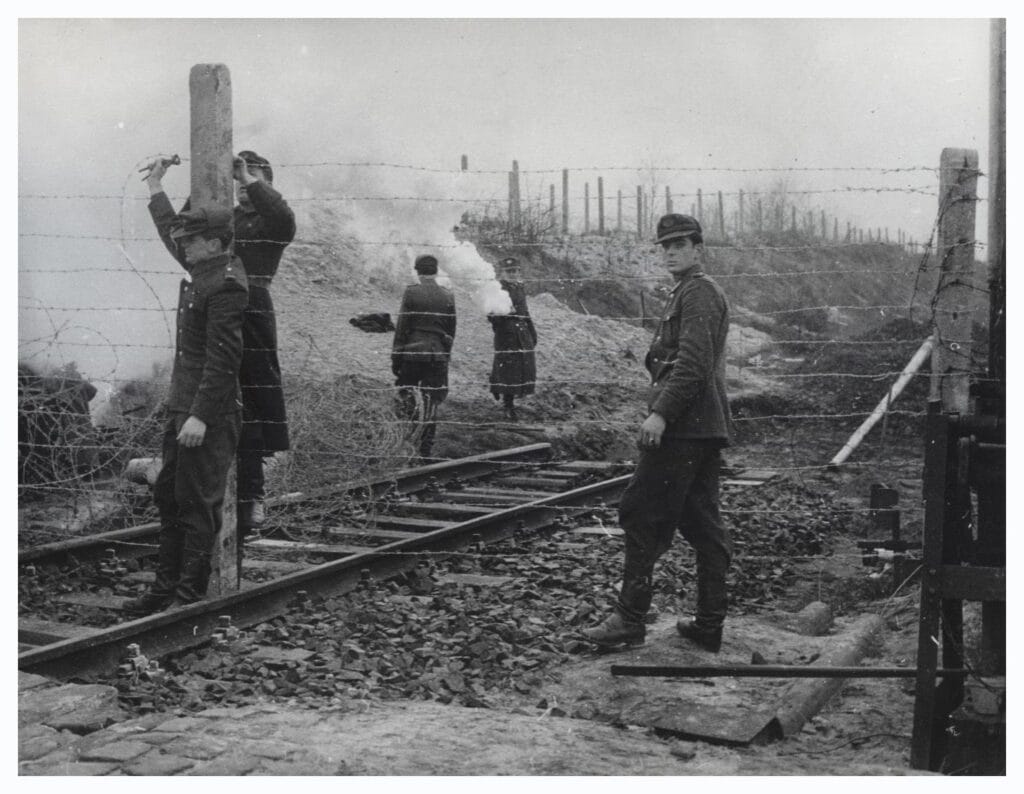

It wasn’t just the rich who left. Everyone tried to get out; students, workers, doctors, and engineers. They were all looking for a better life. This is when East Berlin decided to build a wall. They then marketed it as “protection” from the corrupt West.

But unlike any other wall we know, the Berlin Wall wasn’t built to keep people out; it was built to keep people in.

Joachim’s first escape

Joachim was born right in the middle of this struggle between East and West.

He grew up in the East, but he saw the same things everyone else was seeing. He knew he needed a change.

By the time he made the decision, it was already too late. The Wall was up.

So he escaped illegally. He swam across the River Spree to West Berlin and joined the workforce as an engineer.

His escape, along with a few others, caught people’s attention. It gave hope to those still in the East that they could do the same.

Groups in the West take action

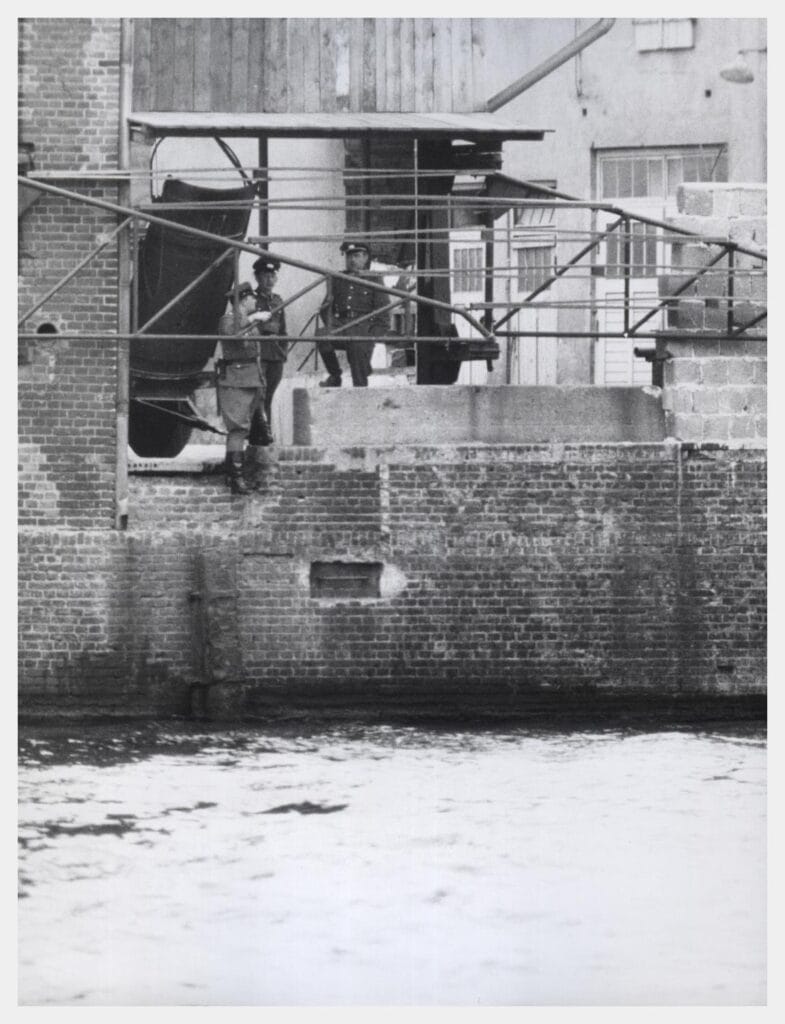

But the Stasi, the Ministry for State Security, quickly took notice.

“The Stasi’s job was simple in purpose: to keep the party, the SED, in power, or, as Mielke put it, the Stasi was to become the ‘sword and shield of the party,’ a phrase he’d copied from the Soviet secret police, the KGB, which the Stasi was modelled on” (Page 58).

That meant people couldn’t escape alone anymore. So groups started forming.

To help these groups, students, activists, and friends-of-friends began creating secret organizations on the West side. They raised funds, recruited people with access to the East, and moved people strategically from East to West.

There were some failed attempts, but for the most part, they were successful. Thousands of people made it out from East to West in a very short period of time.

The Stasi fights back

The East German state, of course, didn’t let this go unchallenged.

The Stasi were everywhere; watching, listening, infiltrating. Every success by escape groups made them more paranoid and more aggressive.

Spies were everywhere, and the Stasi made sure nothing passed between East and West without their knowledge. The amount of research they did was breathtaking.

“Then—the strangest discovery—thousands of jars, all numbered, each containing torn pieces of cloth. These pieces of cloth had been placed in suspects’ armpits or crotches during long, sweaty interrogations, then put in sealed jars as smell samples, ready to give a sniffer dog should they need to find the suspect again” (Page 109).

The first tunnel: trial and error

Despite all this, people were still desperate to escape. They kept trying.

But they knew they had to up their game. That’s when the tunnels started forming, from East to West.

One day, a group in the West that was helping people escape from the East contacted Joachim. They asked him to help build a tunnel for some people to get out. He realized he could contribute with his engineering knowledge.

So they got to work.

But tunneling wasn’t straightforward.

“How do you dig your tunnel when you can’t use machines in case you’re heard by one of the most powerful secret police forces on earth? How do you buy tools when you have no money? How do you avoid hitting a pipe and drowning? How do you see in the tunnel when there’s no light? How do you breathe when the air runs out? And if, somehow, you do all this, and you get to the other end, what if the secret police are waiting for you?” (Page 130)

They had to avoid the Stasi by digging where no one would suspect. They chose a place nobody would expect: Bernauer Straße, one of the most popular streets divided by the Berlin Wall.

At first, it seemed like an unusual choice. The Wall ran literally down the middle of the road; buildings on one side in East Berlin, and the sidewalk on the other side in West Berlin. And it was always a busy street.

But the pros outweighed the cons:

- The soil was soft, so digging would take less time.

- The noise wouldn’t carry to the top or alert the Stasi, the road work acted as a shield, and the street was always noisy.

- Most of all, nobody would suspect anyone would dig a tunnel in such a popular, visible place along the Wall.

It was a bold project, but Joachim and his team soon saw the flaws. The tunnel got flooded. The project eventually failed.

And yet, people kept trying. The first tunnel project was daring but flawed. Digging under a city isn’t simple. The soil collapsed, water seeped in, and the young men doing the digging were out of their depth.

The tunnel failed, but it was just a rehearsal. They had learned what not to do.

The second tunnel: a well-refined attempt

Some time went by, and the number of people waiting in the East kept piling up.

A new way out was needed.

Then Joachim realized there was another tunnel, one that had been abandoned halfway through digging.

This tunnel was different. There were no leaks, and the soil was holding up well. That made digging harder, but it didn’t stop Joachim and the team.

This time, they were sharper, more determined, and better organized. They dug deeper, longer, and with careful planning.

The scale is hard to imagine, 135 meters long, carved entirely by hand with shovels and buckets. Photos from the time show tight wooden beams barely holding the soil in place, a narrow crawlspace that looks terrifying even on paper.

And yet, that claustrophobic passage became the route to freedom.

The final escape

On September 14, 1962, the tunnel was ready.

They signaled the people planning to escape to enter an apartment block on Chönholzer Straße, one by one, so as not to draw attention, and move through the tunnel to the West.

One by one, people escaped. Joachim was the last to go, making sure everyone else got through first.

By this time, the tunnel was in really bad shape. It was already flooding. Right after Joachim crossed to the other side, part of the tunnel on the East side collapsed, and it.

But months of hard work didn’t go to waste. Everyone had made it out.

That day, 29 people escaped, giving the tunnel its name.

Ideas that resonate with me

One war ends just to give birth to another

Carl von Clausewitz once said, “War is the continuation of politics by other means.”

The Cold War is a perfect example. The Allies were divided in a way that could spark another conflict right after the first one ended.

The Cold War dragged on, longer and more cumbersome at times than the Second World War. It took 44 years for the Berlin Wall to finally come down.

That shows just how tired and scared people were, even to make a single rebellious move.

Nobody wins in a war

And, as always, there are no winners in war, only survivors and victims, left to deal with the lasting scars of destruction, loss, and the moral compromises forced upon them.

The book also touches on the Russian Red Army’s brutalities when they took control of Berlin at the end of the Second World War, showing that even the so-called liberators could become oppressors. It’s a reminder of how war corrodes humanity on all sides.

A TV crew joins the story

One of the wildest parts of this story is that it wasn’t just underground activists and desperate families involved.

NBC, the American broadcaster, actually funded and filmed the second tunnel project. They put up money in exchange for the rights to the footage.

The result was a documentary that shocked the world when it aired. The East German government was furious. The Americans scrambled to handle the political fallout. And ordinary viewers? They sat at home watching real people crawl into freedom.

For once, the Cold War wasn’t abstract. It was flesh and blood on their TV screens.

The documentary became one of the most influential of its time. It attracted 13.5 million viewers, a remarkable feat for a documentary back then.

Parts that left a mark on me

What made this even more extraordinary was that the American planes that brought food were the same planes that a few years earlier had dropped bombs. Rosinenbomber–‘the raisin bombers’–the pilots were called(page 39).

By 1961, East Germany had lost three million people–around a fifth of its population. That year, each month, the numbers increase: in June, 20,000 leave; 30,000 in July. Soon, the deluge of people leaving becomes so great that a new word is coined to describe it: Torschlusspanik–‘the rush to get out before the door slams shut’.(page 63)

Compared to other walls in history, the Berlin Wall in its early stages is shoddy, an embarrassment of engineering. One onlooker says it looks as though it’s been put together by ‘a band of stonemasons when drunk’. But it is unique in one respect: most walls in history have been built to keep enemies out. This is one of the only walls built to keep people in. (page 83)

How did the book change the way I think?

In war, everybody loses.

Coffee chat

What really happened in Tunnel 29: The True Story of an Extraordinary Escape Beneath the Berlin Wall?

Tunnel 29 tells the story of 29 people who escaped from East Berlin to West Berlin.

A social activist group from West Berlin dug a tunnel from West to East across the Berlin Wall and helped 29 people escape from East to West.

This escape became the first major embarrassment for the East German army, the Stasi.

A documentary followed, showing actual footage of the tunnel being built and people making their escape. It became one of the most influential documentaries of its time, reaching 13.5 million viewers.

Summarize Tunnel 29: The True Story of an Extraordinary Escape Beneath the Berlin Wall in three paragraphs.

The Second World War had just ended, only to give birth to another conflict: the Cold War between East and West.

The Berlin Wall symbolized the peak of the power struggle between these two sides. Unlike other walls, this one was built to keep people in, not to keep enemies out. It was designed to stop people from escaping East to West, from communism to capitalism, in search of a better life.

Joachim, a 22-year-old engineering student at the time, was asked by a student activist group in West Berlin to help a group of people escape from the East. The plan was to build a tunnel under the Wall.

The first tunnel project failed because of flooding. But they didn’t give up.

They found another abandoned tunnel, half-dug and unfinished, and jumped on it. After months of work, it was finally ready on September 14, 1962. That day, 29 people escaped. This is the highest recorded number in a single operation at the time.

Read the original post about this story by Helena Merriman herself here: The story of Tunnel 29.

Who was Joachim Rudolph in Tunnel 29 and how did he lead the escape beneath the Berlin Wall?

Joachim Rudolph was born and raised in East Germany.

Like many, he was frustrated with life under communism. He made a solo escape to the West(west Berlin) by swimming across a river.

One month later, a student group contacted him and asked for help building a tunnel to get people out of the East. Armed with his engineering knowledge and a willingness to make a change, he agreed.

This book is based on the conversations Helena Merriman had with Joachim several decades later. Merriman mentions in the book that Joachim has a razor-sharp memory of all the details, even decades after the incident.

How many people escaped through Tunnel 29, and what risks did they face?

Twenty-nine people escaped through the tunnel, giving it its name.

The tunnel was constantly flooding. At one point, the diggers accidentally broke a waterline and had to work hard to drain it.

On the day of the escape, the tunnel was already filled with water, and the level was rising fast.

Despite that, everyone who was planning to escape made it out that day.

Explain how the theme of betrayal is developed in Tunnel 29, especially in relation to the Stasi informant.

In the middle of the book, Merriman introduces a new storyline about a Stasi informant named Werner Stiller.

He secretly reported on some planned escapes ahead of time. He was also part of the student activist group that led Tunnel 29 from the West Side.

But somehow, the information about Tunnel 29 never made it to him.

How accurate is the depiction of the Stasi informant in Tunnel 29: The True Story of an Extraordinary Escape Beneath the Berlin Wall?

All the information about the Stasi informant, Werner Stiller, comes from interviews, court records, and archival documents.

One thing about the Stasi is that they kept records of everything. The author takes full advantage of this, showing how Stiller joined the Stasi and detailing all the interactions between him and the agency following the Tunnel 29 escape.

Analyze the character motivations in Tunnel 29. Why did the students risk their lives to build the escape tunnel?

The city was divided in half by the Berlin Wall.

Everyone, no matter which side they were on, had a reason to escape the East, or to help others escape. Even people in the West had family in the East.

Student groups, the main character Joachim, and most of the members who dug the tunnel had someone they cared about on the East side.

That personal connection was the main reason they kept trying, even after failing several times.

What does the ending of Tunnel 29 suggest about freedom and resistance under oppressive regimes?

Tunnel 29 was a huge statement to the East Communist regime.

It was the biggest escape at the time. It showed that people weren’t completely submitted to oppression. They were willing to risk their lives to break free.

This became one of the key reasons that eventually led to the fall of Communist East Berlin.

Compare Tunnel 29 to other Cold War escape stories. What similarities and differences emerge?

Right after the Berlin Wall was built, there were still many solo escapes.

It was doable because the Wall wasn’t fully completed yet, and the Communist army wasn’t organized enough to stop people.

But escaping soon became much harder. Jumping over walls, climbing fences, or using fake passports weren’t reliable options anymore.

That’s when tunnels started to appear. Tunnel 29 helped 29 people escape, and many more escapes followed using tunnels after that.