Hiking Through History

On a calm, sunny day in the middle of summer, I was hiking up a steep trail above the small town of Field, British Columbia.

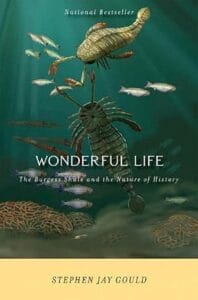

The trail leads to one of the most scientifically significant fossil sites in the world: the Burgess Shale. I’d read about it before, but standing there, surrounded by the vast Canadian Rockies and knowing that beneath my feet lay the remains of creatures from over 500 million years ago, hit differently. I’d brought along a copy of Wonderful Life by Stephen Jay Gould and ended up finishing it the day after the hike, feeling a whole new appreciation for the improbable path that led to us.

What a time to be alive! You can just hike for six hours and end up holding a piece of deep history in your hand. The more I think about the Burgess Shale, the more it feels like a meditation on time, chance, and the sheer randomness of our existence. Gould’s enthusiasm, his philosophical tangents, and his storytelling all clicked into place once I got to hold one of those fossils in my own hands.

A Story Like No Other

Wonderful Life tells the story of the Burgess Shale and the strange Cambrian creatures whose fossils were preserved there; not just as scientific curiosities, but as philosophical challenges to how we understand evolution. The Burgess Shale, tucked away in Yoho National Park, British Columbia, holds dozens of bizarre, soft-bodied creatures from around 508 million years ago, during the Cambrian Explosion. To put that in perspective, it’s about 160 million years before the dinosaurs went extinct (they disappeared around 66 million years ago). This Cambrian Explosion is often called the “Big Bang” of biology because it’s when complex life suddenly diversified in ways we still don’t fully understand.

And the way these fossils formed is almost miraculous. Most people picture fossils as big dinosaur bones, hard skeletons turned to stone over millions of years. But the Burgess Shale fossils are different. These creatures were mostly soft-bodied, that is, no bones or shells to protect them; so it’s surprising they survived at all.

One day, a mudslide, probably from an underwater avalanche, swept these little animals off the seafloor and buried them fast. That mud sealed them off from oxygen and scavengers, which made all the difference. Instead of rotting away, their bodies were preserved in stunning detail; gills, guts, even tiny hairs. So while dinosaur fossils show us ancient skeletons, Burgess Shale fossils show us the very blueprints of life; delicate, strange, and wonderfully complete.

As Gould puts it:

“To be preserved as soft-bodied fossils, these animals had to be moved elsewhere. Perhaps the mud banks heaped against the walls of the escarpment became thick and unstable. Small earth moments might have set off ‘turbidity currents’ propelling clouds of basins that were stagnant and devoid of oxygen.” (Page 70)

“Very few specimens show signs of decay, implying rapid burial: no tracks, trails, or other marks of organic activity have been found in the Burgess beds, this indicating that the animals died and were overwhelmed by mud as they reached their final resting place.” (Page 70)

In simple terms, the major branching of species that led to modern animals happened during this Cambrian Explosion. Before that, life was simpler and less diverse. So the creatures from the Burgess Shale are really the “Oldest Ones.”

Gould walks us through the site’s discovery, early fossil interpretations, and most importantly, the radical reinterpretations from the ’70s and ’80s that showed just how strange and diverse these creatures really were.

His big idea is that If you could rewind the tape of life and play it again, the outcome might be totally different. Maybe even… no humans.

The Cast of Strange Characters

The species found in the Burgess Shale are just as bizarre and fascinating as the event that preserved them. Gould introduces us to a cast of evolutionary oddballs, creatures so strange they’d be more at home in a sci-fi novel than in Earth’s fossil record:

- Hallucigenia: spines on one side, legs on the other, famously reconstructed upside down for years.

- Opabinia: five eyes and a claw-tipped vacuum-like trunk.

- Marella : the most common fossil, with delicate limbs and feathery gills.

- Wiwaxia: slug-like with armoured scales and spines.

- Anomalocaris: a large predator with grasping appendages and a circular, tooth-filled mouth.

Each of these species represents an evolutionary experiment, a body plan that often went nowhere, disappearing without a trace. They remind us life on Earth is far less linear and far more fragile than we might think.

Gould, the Storyteller

As unique as these creatures are, Gould’s writing style is just as distinctive. Even after reading just a few pages, I got the sense that his approach is a bit radical for a nonfiction book, but in a good way.

Gould isn’t a minimalist. He’s exuberant, curious, and unafraid of long, fascinating detours into history, philosophy, or personal reflection. He is generous with his knowledge.

Reading Wonderful Life feels like chatting with a brilliant friend eager to share everything. His passion shines on every page, and his metaphors stick long after you’ve put the book down. He writes evolution not as a cold, mechanical process but as a dynamic, unpredictable story. It’s not a light read, but it rewards your focus with insight after insight, never losing respect for the reader’s intelligence, even in highly technical sections.

Contingency, Not Destiny

At the heart of Wonderful Life is a radical but compelling idea: evolution isn’t a steady climb toward complexity or perfection. It’s more like a branching bush, a messy, sprawling, and full of dead ends.

Most of those branches never made it past the Cambrian. Gould argues that the creatures of the Burgess Shale reveal a much wider variety of body plans than anyone expected; forms so strange that early paleontologists tried to squeeze them into familiar boxes, assuming they were just crude ancestors of today’s animals. But as later studies showed, many of these creatures weren’t early versions of anything. They were evolutionary experiments with no modern descendants.

And that changes everything.

Life didn’t march predictably toward us, Homo sapiens, the supposed pinnacle of evolution. Instead, our existence is just one lucky outcome among countless possibilities. As Gould reminds us again and again: it wasn’t destiny. It was chance.

Rethinking Natural Selection

These insights from Wonderful Life reshape our view of evolution itself. Instead of a neat tree slowly branching out from a common trunk, Gould shows us something much more chaotic, and the Burgess Shale is his proof. The fossil record there doesn’t show a gradual, directional process. It looks more like a sudden burst, a flat line of strange, diverse body plans appearing all at once, each starting its own evolutionary path. There’s no clean trunk leading to us, just a wild tangle of beginnings, most of which ended in extinction. These creatures weren’t evolving toward something, they just…were.

Gould’s key point is that evolution isn’t only about survival of the fittest, it’s also about survival of the luckiest. Many species that made it through the Cambrian didn’t have clear advantages; they just happened to survive. Meanwhile, others that may have been better suited didn’t.

The Burgess Shale challenged Darwin’s original theory in some fundamental ways. Darwin expected to find gradual transitions between major animal groups; a slow, step-by-step buildup of complexity. But these fossils show something else entirely: fully formed, highly varied body plans appearing almost out of nowhere, without obvious transitional ancestors.

Thanks to rapid burial and exceptionally rare preservation, we can see this evolutionary moment in stunning detail. And it’s weird. Beautifully weird. It forces us to rethink life’s history not as a smooth arc, but as a fragile, chaotic experiment, full of false starts and lucky breaks.

Modern biology has since worked to integrate this data, using genetics and developmental biology to explain parts of this sudden burst. But that original mystery still holds its power: what if chance had played out differently?

What if we weren’t the result?

The Final Star: Pikaia

One creature is saved for last in the book; “saving the best for last,” Gould says. It was the final fossil studied by Simon Conway Morris and the last one mentioned in Wonderful Life. And it’s easy to see why: because Pikaia might be the most important character in this story of chance.

At first, Pikaia was misclassified as a worm, a humble annelid, but later work revealed it was one of the earliest chordates: animals with a notochord, a flexible rod that would later become the backbone.

That’s a big deal in evolution.

When Gould wrote the book, Pikaia was the earliest known chordate fossil. Others have since been found, but Pikaia still holds symbolic weight, a fragile thread from the Cambrian seabed to us.

Because all vertebrates—fish, sharks, Dimetrodon, dinosaurs, horses, dogs, chimpanzees, and humans—share that chordate design. Pikaia is one of the first known creatures to have it.

Here’s the twist: Pikaia wasn’t dominant or common. It had no obvious advantage over the other bizarre Burgess Shale animals. If it hadn’t survived, vertebrates, and we, wouldn’t exist.

There’s no grand victory. No “fittest” narrative. Pikaia just… made it.

And we, the homo sapiens, are its legacy.